The wraith

by J. Robert LennonCarl Blunt was fully aware when he married her that Lurene was an unhappy woman, and he’d had no illusions about the possibility of her ever changing. She had told him as much when they met: “I’m not happy,” she’d said, on their second date, a dinner followed by a walk along the lake, “and I’m never going to be.” His response at the time had been a silent nod of understanding. Later she would tell him that this had clinched her conviction that he was the one; he was the only man she’d ever met who hadn’t tried to talk her out of it. He still hadn’t. His job was to acknowledge her unhappiness, accept it, and attempt, in ways that did not question her right to it, to comfort her in its throes.

Carl was a large man, over six feet and thick around the middle, and he liked being that way. He viewed his physical size as a single facet of a comprehensive personal identity, which also included among its primary features a quiet competence in all manner of practical tasks (filling the dishwasher, making things level, reading maps), an unerring mental fastidiousness, highly focused and slightly unorthodox artistic tastes, and a calm, friendly, unemphatic manner.

He was attracted to Lurene because of her narrow hips, large breasts, wide face, stooped walk, and pessimistic worldview, and ten years of marriage had in no way diminished his attraction. If anything, she was more herself than ever, her hips thinner, face wider, breasts larger. She stooped no lower than before, but she gave the appearance of doing so, due to what years of unhappiness had done to her face. It was still pretty, hadn’t taken to wrinkling and sagging, but its flesh had taken on a grave heaviness that levity was powerless to penetrate. They had agreed when they married never to have children, and he was glad they had stuck to that promise, because it just would not have worked. They were too self-absorbed. They felt proud of themselves for knowing this.

Carl was thirty-three. Lurene was thirty-one.

There was one element in their lives that Carl hadn’t counted on when he married Lurene, a single wild card. That was politics. Lurene hated George W. Bush, utterly loathed him. This was 2005. She screamed, literally screamed, when she saw Bush’s face, which fortunately was not very often, because they had sworn off television news after the 2000 election, and because Carl got to the paper before she did each morning and was able to tear out any photos and throw them away. Lurene nevertheless often growled at the empty space Bush’s face had occupied.

News of the latest atrocities struck her with the force of stones flung into the sea; they made their mark with a pale splash, and then vanished underneath the monotonous pummeling waves.”

Neither of them had ever been very politically aware, nor was anyone else they knew, back in the nineties. Carl could remember one or the other of them vaguely disapproving of something Clinton did now and then, and he could recall them both being very annoyed by the impeachment hearings of 1998. But nothing seemed of great consequence. They regarded the world as working more or less as it should, and concentrated on themselves, earning money, being married, and pursuing their various interests. They were content.

But Bush brought something out in Lurene that Carl hadn’t known existed. When the Supreme Court voted to stop the recount, Lurene picked up the transistor radio that Carl’s uncle had bought them as a wedding gift four years before, and she threw it against the kitchen wall, where it split in half, spilling electronic parts on the floor. After September 11, which Lurene blamed Bush for failing to prevent, and the invasion of Afghanistan, of which Lurene did not approve, such incidents became commonplace. She swept books off shelves, overturned chairs, and kicked a dent in the sheetrock wall of their apartment. She snarled at passing cars. When Bush invaded Iraq, she stopped having sex with Carl, and then only agreed to resume relations if she could crouch on her knees and press her raving face into the pillow. If he wanted it any other way, he had to catch her before sunrise, before she’d fully woken up, before the horrible world possessed her.

Abu Ghraib made her vomit, and when Kerry lost, she burned her own hand on the stove top on purpose.

For his part, Carl didn’t like the president either. Indeed, he disliked the man very much, the whole lot of liars and fascists. But he didn’t complain, because he had no intention of doing anything about it. He didn’t go to protests or marches, didn’t blog his opinions, didn’t stage voter-registration drives or man phone banks. His sole rebellion was his vote, which he cast every four years. He didn’t think this entitled him to much acting-out. And so he kept his opinions to himself.

But at some point during the era of Hurricane Katrina, Valerie Plame, Jack Abramoff, and warrantless wiretapping, Lurene’s misery reached a disturbing new nadir, a state of steady and imperturbable deadness. News of the latest atrocities struck her with the force of stones flung into the sea; they made their mark with a pale splash, and then vanished underneath the monotonous pummeling waves. At breakfast, she and Carl carried on conversations like this:

“If you get out of that meeting before six, let’s go to Jason’s for dinner.”

“—”

“More coffee?”

“Mm.”

“You look pretty this morning.”

“—”

The fact was, she didn’t look pretty this morning. She looked ghoulish. Her hair had gone lank, her face ashen, her eyes sunken into purple calderas of damp flesh. Her lips were bitten raw and her clothes hung crookedly on her body. Several times each day, Carl found her frozen in some prosaic tableau, her mouth hanging open and her lips twitching, one hand flopped like a hunk of rotten fish on the kitchen counter or off the edge of the bed. And then, as if prodded with electrodes, she would jerk, cough, and start up again, ploughing into whatever was left of her day.

One night, Carl tried to talk to her about it.

“You seem different lately,” he said gently, his hand resting ajitter on her bony knee.

She shrugged, turned the page of her magazine.

“I’m afraid you’re falling into…”

“Don’t say it, Carl.”

“… that you’re suffering from…”

“Don’t.”

He stopped, pulled his hand away, settled back into his little nest of throw pillows. Depression, he didn’t say. The word, with all its clinical associations, was forbidden in their house. It cast unhappiness as a problem, one that could, and should, be solved. Depression was a frailty. Unhappiness, on the other hand, was a way of life. Lurene insisted upon the distinction and had lodged herself permanently and immovably in the unhappiness camp. End of discussion.

Three days before Valentine’s Day, a holiday they habitually, pointedly did not celebrate – Lurene broke through the floor of her misery and into some annihilating sub-basement of agony.”

But not end of problem, because she got worse. She walked around crying. She began taking sick days off work. She smoldered with resentment for Carl and his asshole, cocksucking bonsai trees and 1920s jazz and arugula, and she took to spitting in his path, as if to curse him, or at least make him slip and break something.

And then, on an unseasonably warm morning in the middle of February – three days, in fact, before Valentine’s Day, a holiday they habitually, pointedly did not celebrate – Lurene broke through the floor of her misery and into some annihilating sub-basement of agony. He heard her fall: she was standing at the kitchen counter in her business skirt and white blouse, pouring milk into her coffee, and her knees buckled, her hands found the countertop, and a sound escaped her, a mortal, creaking gong, like a pair of rusted cemetery gates at long last falling open. And once they did, the furies poured through, and Lurene keened like a dying animal, and tore open her blouse, scraping red lines down her neck and chest.

Carl had been trying to read an article in the paper about third-world debt relief around the ragged Bush-hole he had torn in the other side. He threw the paper down and leaped to his feet. He ran across the room and caught his wife as she fell.

“Let go of me,” she wailed, but made no move to push him away. She collapsed into his body, knocking him off balance, and the table barked against the linoleum floor as it jumped away from his palm.

“My God,” he said. “Lurene.”

She resisted, righted herself, pressed her hands to his chest.

“Let me go.”

“I won’t.”

“You will, you fuck.”

“I won’t.”

But he did. He caught his balance, she caught her breath, and he allowed her to extricate herself from his embrace. For a moment they stood facing each other, panting, unsteady on their feet.

“Maybe you should lie down.”

“I’m going to do it, Carl. I am.”

“No, you won’t.”

“I’m going to kill myself,” she said. Her face tilted up to his, trembling as if it might shatter, cutting him to shreds with its pieces. This was new. This, he had never before seen.

“You won’t. You will not.”

Her only reply was a sigh.

“You’re exhausted. You need to rest.”

Her head shook no, no.

“Lie down. I will be right there. Lie down.”

She sighed again and turned toward the bedroom.

“That’s it. I’ll call in to work for you.”

She dragged herself away and disappeared down the hall.

As soon as she was out of sight, he took two swift, heavy steps to the phone where it hung on the wall. He picked it up and pressed 9, and a moment later pressed 1. He heard, from the bedroom, the sound of the bedsprings compressing, and drew breath. He gazed at his newspaper where it lay, the plate of cantaloupe humped below it, and at the dark gray stain limned by its wetness. His finger hovered over the 1.

Then his eyes traveled to the counter where Lurene had fallen and saw the cutting board, covered with the rough husks of his breakfast. It was wrong somehow, and he stared at it. In the bedroom, Lurene emitted a high, pneumatic whine. A chill ran through him.

The paring knife was missing.

He gasped, dropped the receiver. It bounced against the wall, thudding hollowly as an old bone. He spun and lunged into the hallway.

She was there.

For a moment he thought it was someone else. She was standing straight, her shoulders thrown back, her head held high. She was buttoning her blouse back over her unblemished chest and neck. Her eyes were bright, and something was the matter with her face.

She was smiling.

“Lurene?”

“God,” she said, with a little laugh, “sorry about that!”

He stared. She shook her head and advanced toward him with a kiss. It made a soft hot smack against his cold lips.

“I have no idea what came over me,” she said. There were tears on her face, and she cheerfully wiped them off with a quick finger, as if they’d blown onto her from somewhere outside. “But I feel much better.”

She moved past him to the coatrack and shouldered on her heavy jacket.

“I thought…” he stammered.

“Me too!” She gawked at him for a long moment, then let out a mighty equine guffaw. “For a minute there, I wanted to die.”

“So you said.”

“I’m really sorry.” She pulled her woolen cap out of her pocket and popped it onto her head. Her hair pressed against her cheeks and five years dropped off her in an instant. “I scared you. I’m sorry.”

“It’s all right.” He slumped back into his seat.

“It was just, you know, everything, it just came down on me all of a sudden.” She had her purse now, her keys, her hand on the doorknob.

“I thought you took the knife.”

She blushed. Blushed! Lurene had never once blushed, as far as Carl could remember. She said, “I did,” and immediately clapped a prim hand over her mouth. Her fingers parted, her lips poked through, and she said it again. “I don’t know what I thought I was going to do. But something snapped, and I felt better.” She shrugged. “Gotta go. I’m sorry, sweetie.

Sweetie?

She blew him a kiss (blew him a kiss?) and walked out the door. Her sprightly steps clicked on the stairs, and a minute later he watched out the window as she half-ran, half skipped across the street and down into the subway.

…

He sat for a short while in stunned silence, listening to the radiator clanking and drops of water leaking into the sink. Sweat poured down his face and into his collar and he tried to slow his breathing.

Carl worked at home. He maintained various websites. Some of the websites he maintained actually sold web hosting and design. His livelihood was entirely ephemeral, a direct-deposited paycheck wafted on a breeze of multilayered virtuality. Every day he wondered if he really, truly, was going to do it – was he actually going to sit down and work again? It just didn’t seem real. And then, every day, he went ahead and did it, and the money mysteriously arrived in his bank account. And often he spent it on imaginary things – music downloads, software. When occasionally some physical artifact of his labor arrived in the mail – a tax form, an invoice – it always gave him a jolt.

But today especially, this sense of unreality permeated the apartment. For the first time in as long as he could remember, he considered going back to bed and sleeping it off. Restarting the day in a different frame of mind. He sighed. The computer waited in the study for him to power it up, and the stain on his newspaper spread. Any moment now, he would get up and do something, anything, to break the spell. And then he heard the bedsprings creak.

He was still for a good thirty seconds. Then, idiotically, he said, “Lurene?”

Of course there was no response. The creak was not repeated. Nevertheless, he couldn’t resist saying her name a second time. More quietly now, more to himself than whatever phantom his imagination had inserted into the next room.

“Lurene?”

The nothing that resulted caused him to flush with embarrassment, and his sweating redoubled. He let out a low, quiet chuckle.

It was time to go to work. He would take a shower, get dressed, then call Lurene at her office to make sure she was all right. There – a plan. He was stirred out of his stupor. He got up and walked down the hall and had his tee shirt halfway up over his head before he even got to the bedroom. He stepped over the threshold, freed his ears from the collar, and tossed the shirt onto the bed, where it struck a naked woman in the back.

He screamed. The shirt slid onto the bunched bedclothes. The naked woman didn’t move.

She faced the opposite wall, her head in her hands. Beside her lay the paring knife, dark with blood, and blood stained the sheets it lay upon.

For a moment, as he recovered himself, he believed that it was her, that it was somehow Lurene. He knew her shape, the pattern of vertebrae, the curve of her neck and shoulders, and these were those. But as he steadied his breathing, as his eyes adjusted to the brackish light filtering through the curtains, he could see that this body wasn’t his wife’s. It was scarred, pitted, scraped. It was gray and battered as a sidewalk, and as lifeless. The back was striated, like a stone plucked from a glacial moraine, as if a lifetime of scratches and welts had never healed, never faded; and it did not rise and fall with the woman’s breaths. There were no breaths. Only his own, growing quieter in the room.

Nevertheless, when he spoke, it was to say, once again: “Lurene?”

It rose to its feet and turned.

The thing that faced him now was like a statue, a statue of his wife, cast in concrete and left to weather, forgotten, in some abandoned town square. It gave the impression of advanced age and great strength, and it stared at him through flat gray-black eyes that did not blink. It wasn’t Lurene, but looked like it was supposed to be.

“Who are you?” he managed to ask.

The thing looked at him. Its stillness was uncanny. It stood with its legs slightly parted, its torso twisted a quarter turn to face him. The wide face, the heavy breasts, the bony hips were flawless facsimiles of his wife’s, hewn from beaten old stone.

And now he recognized some of the marks – a deep cleft in the chin where Lurene had a barely noticeable scar. A long gouge that outlined the pelvis, where Lurene had shed a benign cyst. A gravelly rake across the thigh, faded to pink on the real Lurene, the result of a bicycle accident on their vacation in Europe three years before.

And finally, on the inside of the left wrist, a three-inch laceration, following a vein, that corresponded to no wound he had ever before seen.

Carl and the thing stared at one another for long minutes, his eyes ranging in horrified fascination all over this strange body, the thing’s eyes locked in place upon his own. It did not speak. It did not move – until, at last, it broke its gaze and sat down, in exactly the position of contemplative misery he had found it.

Shirtless, sweating more profusely than ever, he strode down the hall to the phone. He snatched up the receiver from where it dangled, tapped the hook until he got a dial tone, and called Lurene’s cell.

“Hi! I was just thinking about you.”

There was a lilt in her voice, a playful chirp.

“Uh…”

“I know I don’t tell you this often enough,” she whispered. “But I love you. I really do.”

“Thanks.”

She laughed. “‘Thanks’? How romantic!”

“I love you, I mean. I do. But…”

“But what!”

“Lurene?” he said, low and soft. “Lurene, tell me something. Be honest with me.”

“Yes?”

“Did you cut yourself this morning?”

There was a long beat before she said, as if it were the punch line of a joke, “Nnnnno!”

He didn’t say anything. From the bedroom, silence.

“Although,” she went on brightly. “Although it’s funny, I had this idea on the train this morning that I had. I was so upset. I was almost certain I cut myself. But now I feel like it was a dream.”

She stopped, but did not sound finished.

“The thing is,” she went on, “I didn’t. I couldn’t have. There’s no… there isn’t any… cut. On my wrist. There’s nothing.”

“Nothing,” he repeated.

“No.” And now she sounded a bit uncertain. “Why – That is – What makes you ask?”

It was several seconds before he said, again, “Nothing.”

…

He might have told her about the thing, but he didn’t. What would he say? Besides, he didn’t want to puncture her bubble of cheer. She had earned it, after all.

Carl Blunt did no work at all that day. He sent an email to his boss claiming flu. It was so much easier to lie in email than on the phone – he didn’t even have to disguise his perfectly healthy voice. Though he made a couple of typos, for good measure.

After that, he got the hell out of the apartment. He walked through the park, hunkered in his coat, his gloveless hands plunged deep into the pockets. He ate lunch at the pizzeria at the end of his block, went to the drugstore, bought underwear and aspirin, and went to see a movie. He was back at the apartment by four thirty. He hung up his coat, put down the Eckerd bag, and took a deep breath before going down the hall to the bedroom.

He edged around the dresser and chair, pressed himself to the closet door, then leaned far, far out to pluck the knife from the bedclothes. It made a little gluey sound as it detached itself from the puddle of dried blood.”

There she was. She had moved. She was lying facedown on the bed now, her head pushed into the pillow. The pillow was hideously distended, as if she were made of lead. The mattress sagged in the middle.

He plucked up his courage and sidled into the room, staying close to the wall. He edged around the dresser and chair, pressed himself to the closet door, then leaned far, far out to pluck the knife from the bedclothes. It made a little gluey sound as it detached itself from the puddle of dried blood. The thing remained still, and Carl withdrew quickly, scooting out of the room with the knife suspended between his thumb and index finger.

In the kitchen, he washed it, placed it in the dish rack, and sat at the table to wait for Lurene.

Thirty minutes later she walked in the door. She dropped her briefcase on the floor, hung up her coat, did a little pirouette, then came to Carl for a kiss hello. Up close, she looked different. At first he thought it was merely in contrast to the thing in the bedroom. But no: she was different. Her skin was clear and soft as an infant’s, her hair thicker, her eyes brighter. It wasn’t a question of age. Tiny lines still fanned out from her eyes; her cheeks betrayed the slightest hint of future jowls. It was a question of pain. In her face, there was none. It was a face to which no insults had ever been spoken, that had never been slapped or seen a hooded man with electrodes attached to his arms. The scar on her chin was gone. She was utterly, frighteningly unscathed by life.

“Good day?” she said.

“No.”

“No?” She skipped to the sink and began to fill a glass with water.

“I didn’t get anything done.”

“How come?” She sipped her drink, cocked her head, gave him a little grin.

He didn’t answer.

“Maybe you didn’t get anything done for the same reason I didn’t get anything done.”

“What,” he asked, “is that?”

She winked. “Distraction.”

“Okay…”

“I was thinking of other things,” she sang.

“Ah.”

She put the glass down, came to him, and kissed him. She plucked his hand from his lap and pressed it to her breast. “Sexy time!”

“Well…”

“C’mon, don’t be a poop,” she said, hauling him to his feet. She grabbed fistfuls of his shirt and pulled him to her, pressing herself against him. “Let’s go.”

“I think you should go in there alone, first.”

“You want me to get all ready?”

“No,” he said. “I mean – there’s something in there.”

His voice, he thought, was dark with foreboding. But she didn’t seem to notice. She had the cheery obliviousness of a character on television. It was as if he were setting her up for a punch line.

It occurred to him that she was nearly as frightening as the thing on the bed.

“Something special?” she cooed.

“No, Lurene. Really.” He gulped. “Something scary. Something you left there this morning.”

She let go of his shirt, fell back on her heels, pouted. “Are you trying to ruin my fun?”

“Lurene,” he said. “You cut yourself this morning. With the knife. And it… left something. In the bedroom.”

Now, at last, a look of annoyance crossed her face. And perhaps a tiny spark of fear. She held up her hand and unbuttoned the cuff of her blouse.

“Look,” she said. “Nothing. No cut.”

“There was blood in there.”

She scowled.

“And the other thing,” he said.

“The knife?”

“No.”

She stared at him with can-do intensity, like a fighter pilot.

“Okay, ya lunk,” she finally gushed, slapping his chest with a fine ivory hand. “You need a shower anyway. Come to think of it, so do I. I’ll go in there and clean up whatever mess I left and I’ll meet you in the bathroom, whaddya say?”

He swallowed, nodded.

She spun and marched off. Carl remained in the kitchen, standing, listening. Her hard-soled office pumps clomped the length of the hallway, passed onto the carpet of the bedroom, and then stopped. He bent over, straining to hear. Would she scream? Would she run out?

She wouldn’t. She didn’t. She was absolutely quiet, for at least a minute. Carl continued to sweat. The wall clock thunked out the seconds.

And then, at last, her footsteps started again. Slowly now, gently, she took three, four, five steps, and again stopped. The silence this time was longer: two, three minutes. And then he heard the bedsprings creak, and a small, guttural yelp, and a ragged release of breath.

“Lurene?”

He moved to the entrance of the hallway, gazed down at the inch of bedroom he could make out through the distant, foreshortened door.

“Honey?”

A groan, movement on the bed. And then Lurene’s shoes touching the floor, one, then the other. A grunt, and footsteps. One, two, three, four. And on five, she appeared.

Her hand was wrapped around the wounded wrist. Blood seeped from underneath. Her shoulders were sloped, her back bent, her face a mask of misery. “Carl,” she said. “Find the bandages.” And she fell, gasping, to her knees.

…

Every morning for a week, she disappeared into the bedroom to get dressed and emerged cheery and full of life. Every morning she left the thing behind, with Carl, in the apartment. He managed to work with it there – he had to. Sometimes he heard it get up and move around. He had found, on the internet, the word: wraith. The ghost of a person still living. He didn’t know if that’s what it was, specifically; the proper nomenclature hardly seemed important. It was a handy nickname for something that he sure as hell was not going to call “Lurene.” The wraith. Sometimes he could swear it was standing in the hallway, waiting for him. But he never budged from the study except for a quick dash to the kitchen for food, or the bathroom. He did not attempt to talk to it. He tried to be quiet, so as not to bother it.

When Lurene came home from work each day, she would draw him into the bathroom, into the shower, and make love to him there. Never before had she taken the initiative in an act that, under ordinary circumstances, she lacked the reserves of joy even to contemplate; he had always demanded (well – requested, really), she had always submitted. Now, though, he found himself shocked and embarrassed, embarrassed by her ardent desire, by his sudden, livid physical response. Her body was so light, so unencumbered by its own corporeality; every motion was effortless and perfect. And then, even before his lust had managed to leave him, she would go – leave the shower, dry off in silence, and return to the wraith. She could feel its need, she told him. She had to go to it, or it would come to her.

One afternoon it was waiting outside the bathroom door.

The next, it was inside the bathroom – behind the curtain when they pulled it aside.

The day after that they locked the door.

Over that weekend, and the next, Lurene stayed Lurene, and said nothing about the wraith, and so neither did Carl. But on Monday morning, he asked her, as she got up from the breakfast table, if he could see.

“See,” she repeated, as if she didn’t know what he meant.

“See it happen.”

Her frown deepened, her eyes narrowed.

“I want to know,” he said. “I want to know how it happens. How it comes out.”

For a moment he thought she would strike him, but what she did instead was begin to weep. “I don’t think I could,” she whispered. “I don’t think it would work. With you there.”

He stood, took her into his arms. He had not made love with his wife, his entire wife, since these strange days began. He missed her. The other one, the happy one – with her it was too easy. His love needed something heavy to hold it down. He said, “Don’t cry, don’t cry.”

“This can’t go on,” she said.

“It can. It can go on.” Though he knew she was right.

They stood in silence for a time, gripping each other so tightly they could barely breathe. Then she pushed him away, walked down the hall, and emerged a new woman.

…

That afternoon, around lunchtime, he was working on some text formatting, trying to convince a client she didn’t want blinking letters with sparks shooting off them, when he heard the wraith get out of bed. Its feet thudded on the floor, and he heard them dragging dryly across the room, like a pair of sandbags.

He had grown used to its wanderings, and he tried to ignore it. But after a moment, the footsteps continued into the hallway and down it, to stop right outside his door. His fingers paused over the keyboard, and he held his breath. The door wasn’t locked. The wraith had never seemed to show much interest in him without Lurene around.

“Hello?” he squeaked.

The door flew open and crashed into the wall behind it, deepening the depression the knob had dug over years. The wraith was staring at him, its eyes blacker and deeper than ever, and as lifeless.

He jumped out of his seat. “Uhh…” he said.

LOVE stamp by Robert Louisiana, 1973. WIkimedia Commons

It took three long steps toward him and grabbed his shirt in its long gray fingers. It was right there, right up in his face, holding him close. He was not frightened, not yet, but he understood that he was helpless. The wraith had a smell, not a bad smell, like that of wet stones drying in hot sun. A bit of ozone, a bit of rot.

“What… what is it?” he managed.

The wraith pulled his shirt open, and the buttons clattered on the floor. It – she – pushed it over his shoulders and down his arms and tossed it back over her head. She was very, very strong. She reached for his belt.

“Whoa, whoa!” he said, and she stopped. She did not back off. She stared at him. He gulped air. And then took the rest of his own clothes off, without her help.

The wraith pushed him into the bedroom and onto the bed, then settled itself over him like a landslide. Its skin was neither rough nor cold, though it wasn’t as warm as living flesh, and certainly wasn’t as soft as Lurene’s. It had the consistency of scar tissue, rough but yielding. It felt unbreakable. It felt like it would survive for eternity.

And it turned him on! That was certainly a surprise. He touched hips, belly, breasts, and felt as breathlessly eager, as hungry, as lustful, as he had ever felt in his life. He marveled at himself, his breath catching in his throat. How was it possible? But it was. The wraith knew precisely what to do with him, and did it without hesitation. It moved over him, shifting its tremendous weight, sending shocks of pleasure through him. It could kill him in an instant, that was the crazy thing. It could crush him, but instead of feeling afraid, he felt safe. Protected by it. Gentled. Unlike with his flesh wife, he used no condom. It hurt to penetrate and it hurt when he came.

Carl got himself off daily with his giggling fake wife and a lumbering clay monster. The new normal! He began to wonder if this was his fate, to be married to a pair of horny half-women, and he decided that there were worse ways to live out one’s days.”

Its eyes remained open, its lips pressed shut, until it was through. Then it heaved itself up off him and flopped over, facedown on its pillow.

It took a while before Carl realized the whole thing was over. When his heart stopped racing, he picked himself up and tiptoed back to the office. He put his clothes back on, realized he couldn’t button his shirt, then threw it in the trash. He had to walk past the wraith again to get a new one, but it didn’t budge. Somehow he managed to return to work.

When Lurene got home, they did it in the shower again, and the wraith didn’t bother them. He could barely keep it up. And when afterward Lurene emerged from the bedroom, fully herself, she gave him a look. But she didn’t pursue it. Whatever had happened, she didn’t want to know.

…

And so it continued for several weeks, became routine, and he amazed himself at what depths of depravity it was possible to grow accustomed to. The warrantless wiretapping continued, the vice president shot some guy in the face, and Carl got himself off daily with his giggling fake wife and a lumbering clay monster. The new normal! His work increased to full productivity, and the fissure that these strange events had wrenched open simply filled itself in and smoothed itself over. He began to wonder if this was his fate, to be married to a pair of horny half-women, and he decided that there were worse ways to live out one’s days.

But then one morning Lurene came out of the bedroom disheveled, stooped, and utterly whole. He gaped. He didn’t have to ask, but he asked.

“What happened?”

“I can’t do it.”

“Well – can’t you – did you try again?”

A sharp look. “Yes I tried again, you prick!”

He winced, sunk a bit into his chair. “I’m sorry!”

She looked around the room, as if for some obvious solution she had failed to notice. “Fuck,” she said, and pulled on her coat and hat.

“You’re just going to go in to work?” he asked.

“Do you have some better idea?”

He shook his head no.

He spent the entire day in a state of mild anxiety, unaccustomed as he had become to being alone in the apartment. Several times he peeked in the bedroom to see if she’d been mistaken, if the wraith was there. But nothing lay on the bed. His palms sweated and he had to change his shirt often. He did things wrong, then did them wrong again.

He slept on it, figuring it would all make sense in the morning. But it was the same the next day, and the next, and all the rest of that week. And then one night Lurene stumbled from the bathroom wearing an expression of horrified epiphany.

“I know why I can’t do it,” she said. “I’m pregnant.”

Unthinkingly, he added himself to the crowded ranks of men who responded to those words by saying “That’s impossible.” To which Lurene did not lower herself to reply.

He tried again. “We were protected.”

She shrugged, lowering herself onto the sofa beside him. They sat in silence, waiting for this new information to settle itself. The television seemed very loud. Carl turned it off.

“Carl,” she said.

He turned to her.

“You fucked it. Didn’t you.”

He looked at her with what must have been an expression of utter forlornness, and he realized what a weakling he was, that he had no volition, he could only do what he was told, he habitually ignored the world’s ills because he couldn’t abide them, and he had capitulated to her misery, not because it was right, but because it freed him from his own. And then he proved it to himself by saying, “It forced me to. I couldn’t stop it.”

Her slap was not unexpected, nor was it undeserved. But it was unprecedented. It turned his head with a sound like a splintering plank, and though it didn’t hurt, not much, it had all the force behind it of a ton of stone.

His head was hung when she got up from the sofa, and it was still hung when she marched into the kitchen, with what, if he had been paying attention, he would have recognized as her old steely resolve. But the silvery snick of the paring knife being pulled from the block – that he recognized.

He managed to stop her. She meant for him to. Her hand was in the air, the fingers white around the knife; her eyes were trained on the doorway as he stumbled through. He grabbed her by the wrist and she pretended to fight against him, and the knife clattered to the floor. She let herself go limp. He encircled her in his arms and led her back to the couch.

“I want it out of me,” she said, through gritted teeth. She threw off his embrace and rocked back and forth, her lip between her teeth.

“We could… get an abortion,” he said, and regretted it immediately. But she shook her head.

“Not that!” she cried. “The other!”

Her face was wet and livid, the lips trembling, and to his great surprise, Carl gasped and let out a sob. The sound it made was very loud, like a bedsheet being torn in two, and he slumped against the back of the sofa and for a few moments was insensible with grief. When he came around, he was again surprised, this time to find himself in Lurene’s arms, to find her kissing his forehead, his ear, his hair; to find her small rough hands caressing his cheeks, wiping the tears away. “Oh, baby,” she said, and her voice was deep and unhappy and real. “Don’t worry. It’ll be all right.”

That beautiful lie! She had never before uttered it. He buried his face in her hot neck, and he pressed his lips to the vein there, which pulsed and leaped with blood, and they stayed that way for a long time, as out in the world things were bombed, and polls were taken, and money was allocated, and money was spent. To their child, should it be born, none of this would ever be quite real. All of it – the terrorism, the torture, the scandals – would have the hazy quality of near legend, the actual truth just barely out of reach, like a scary campfire tale about something that, swear to God, actually happened to a best friend’s cousin’s roommate. The events, though factual, would seem invented, and the characters would be parodies of themselves, rough outlines, without particular depth or dimension.

A tragedy, Carl and Lurene might have said, that the truth was always forgotten, that history was dulled and simplified until it didn’t resemble itself at all. But they understood that forgetting was the way people managed to go on. Even they would be forgotten, eventually, and once they were gone, their child would come to wonder what they were really like, back when the world was such a storied mess. The child would recall Lurene as firm and stoic, Carl as decent and shy, and the two would seem long-suffering and impossibly old, heavy with the burdens of their age, like statues come to life.

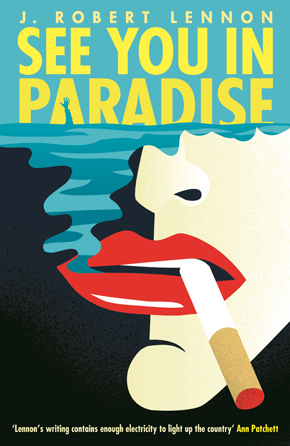

From the collection See You in Paradise, out now in paperback from Serpent’s Tail.

J. Robert Lennon lives in Ithaca, New York, and teaches writing at Cornell University. He is the author of seven novels and the collection Pieces for the Left Hand, stories from which have appeared in the New Yorker, Paris Review, Granta, Harper’s and Playboy. His latest novel, Familiar, a haunting psychological thriller about parenting and memory, is published by Serpent’s Tail, along with the new collection See You in Paradise. Read more.

J. Robert Lennon lives in Ithaca, New York, and teaches writing at Cornell University. He is the author of seven novels and the collection Pieces for the Left Hand, stories from which have appeared in the New Yorker, Paris Review, Granta, Harper’s and Playboy. His latest novel, Familiar, a haunting psychological thriller about parenting and memory, is published by Serpent’s Tail, along with the new collection See You in Paradise. Read more.

jrobertlennon.com

Author portrait © Lindsay France