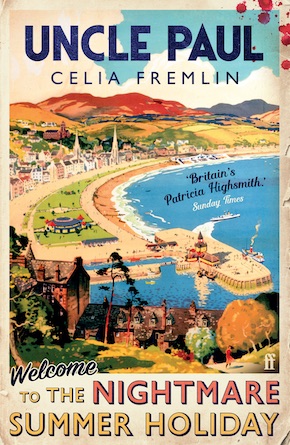

A menacing charmer

by Celia Fremlin

They had come out on to the parade now, and he led Meg into a glass-sided shelter facing out across a sea so smeared and spangled by lights that it seemed as much a man-made structure as the parade itself.

“Now tell me what it’s all about,” commanded Freddy; and without forethought or caution, Meg in the darkness proceeded to tell him.

“It’s something that happened when we were quite small,” she began. “At least, I was quite small. Isabel must have been twelve or thirteen, I suppose – she was at boarding-school already, only she was home for the holidays when it all happened. Mildred had got engaged to a young man called Paul Hartman. At least,” amended Meg, anticipating her climax, “that’s what he called himself. I remember him coming to the house for the first time. He was quite different from any of our usual visitors, and I remember staring and staring. He was very elegant, very dark – rather slight, I realise now, though of course at the time he seemed to me quite tall. I’d never seen anything like his great liquid brown eyes and his dark arched eyebrows, extraordinarily clear-cut against his white forehead. And his voice—”

“It sounds to me,” interrupted Freddy, “as if, in your little innocent heart, you cherished a pretty sizeable crush on the gentleman.”

“Well – yes – I suppose I did,” laughed Meg. “And, you know, he was very charming, there’s no getting away from it, in spite of what happened afterwards. What we found out afterwards, that is to say – it had all happened actually, before we ever saw him. Well, anyway, he made a dead set at Mildred, and she fell for him at once, and after a very few weeks they got married.

Apparently he’d married her for her money, got it made over to himself, and then taken her abroad and pushed her over a cliff. He must have thought he’d finished her off, but he hadn’t.”

“At least,” Meg amended once more, “they had a wedding, and everyone – Mildred too, of course – thought they’d got married. But it turned out later – oh, only two or three weeks later, as far as I remember – the whole thing can only have taken the length of the summer holidays, because I remember how hot it was all the time, and how cool Uncle Paul – that’s what Isabel and I called him – how cool he always managed to look while everyone else was baking. I suppose it was because he was naturally so pale—”

“Oh, get on, my sweet. Cut out the interesting pallor. What happened two or three weeks later?”

“It turned out that he was already married,” said Meg. “And not only that, but the police were after him for the murder – the attempted murder – of his first wife. Apparently he’d married her for her money, got it made over to himself, and then taken her abroad and pushed her over a cliff. He must have thought he’d finished her off, but he hadn’t; and when she got better – or maybe when she began to realise it couldn’t have been an accident – I don’t know – she set the police on his tracks. Just about the time when, under a different name, he was ‘marrying’ his next heiress – Mildred.”

“Mildred an heiress, eh?”

Freddy had lighted a cigarette now, and the tip glowed motionless in the dark.

“Oh yes – I forgot to tell you. Mildred had – has – quite a lot of money left her by her own mother. That’s why he fastened on her, of course. He was planning the same thing all over again.”

“I see. But his plans were foiled, in spite of the false name. By whom?”

“It – it was Mildred,” said Meg uncomfortably. “She – she found out somehow who he really was, and went to the police. He was arrested at our house early one morning, before breakfast. I remember waking up and hearing a lot of shouting and tramping of boots – but you know how it is when you’re a child, everyone tells you not to worry, and everything will be all right: we never did find out exactly how it all happened. And it’s no good asking Mildred, because she tells it differently every time, according to whether she wants to appear as the innocent young girl betrayed by a scoundrel, or as the astute amateur detective to whom police and public owe undying gratitude. Anyway, he was brought to trial, given a long prison sentence, and that was the end of it – or should have been; but now that his time is up, Mildred’s been getting into a state about it all over again. And she’s managed to get Isabel worked up about it as well – Isabel is so suggestible, you know—”

Here Meg related the story of Mildred’s stay at the cottage; her terror at the mysterious footsteps, and her far-fetched suggestion that they might be Paul’s.

“It sounds to me like a lot of hysterical nonsense,” finished Meg. “But Mildred thinks – or, just for the drama of the thing, pretends she thinks – that Paul has come back to find her, and to take his revenge.”

“Revenge.” Meg wished that she had turned her sentence differently, so that this word had not come at the end, ringing solitary through the darkness. And what made it worse was that Freddy did not immediately answer. Dimly she could see his profile, staring out towards the battered brilliance of the tamed and defeated sea.

“Both of them,” he said at last; and for a moment, in the darkness, Meg did not know to what he was referring.

“Both of your sisters,” he continued. “It would seem that on this subject they are agreed. In real life, apparently, as Isabel was saying, women are quite ready to betray the man they love. I didn’t know.”

Meg knew, then, that she had told the story in too casual, too flippant a manner. It had jarred upon him. But – too flippant for Freddy? It wasn’t fair of him to be so frivolous, so cynical nearly all the time, and then suddenly turn serious in unpredictable flashes like this. She felt snubbed, rebuked, and her determination to justify herself could only take the form of an exaggerated defence of Mildred.

“That’s not fair!” she cried. “Not in Mildred’s case. She didn’t love him any more, you see. You can only talk about loyalty where there is a love to be loyal to. She hated him once she knew what he had done – and that he’d only wanted her for her money in any case. She just wanted to be rid of him. No, what was worrying her most, I think, was the sort of publicity it was getting. The papers didn’t make her seem either a betrayed innocent or a supersleuth – they just made it all sound sordid. They must have been full of it for weeks. Even I can remember it, though I can’t have read papers much at that age. I do remember very clearly seeing a paper on the kitchen table with Uncle Paul’s photograph in it. The photograph of him as he was, I mean, before he met Mildred. He’d disguised himself a bit since then, shaving off his moustache and so on, but I could still see the likeness. I remember covering the moustache with my finger, and seeing how exactly like the rest of it was; and then I went off into the garden to look for Uncle Paul to see if he really did look like that.”

“But, of course, Uncle Paul wasn’t there by that time; he’d be safe behind bars,” said Freddy, staring in front of him.

“Well – yes. Now I come to think of it, he must have been,” said Meg. “But it’s funny, I seem to have a distinct recollection of finding him under the rose arch, smoking a cigarette and looking over the smoke at me in that queer, sparkling way he had. But it must nave been some other occasion, obviously.”

“Obviously.” Freddy took several more puffs at his cigarette. “And all this, you think, explains our Isabel’s little outburst this evening?”

“Oh, yes.” Meg was quite positive. “She was feeling rather – you know – on edge about Mildred’s affairs altogether, and then you bringing up the subject of wives whose husbands are murderers – well, naturally it upset her. She was sort of defending Mildred – pointing out the conflict she must have faced. Though I don’t think, actually, that Mildred ever saw it as a conflict at all, not in the way that Isabel would. I think she just saw it as an unsavoury situation to be escaped from as completely as possible – or sometimes to be dramatised, in suitable company. She’s never been a person to look all round things, and worry, and weigh them up, as Isabel does.”

“And you? Which sort of person are you?”

“Me?” Meg was startled. “How do you mean?”

“I mean,” Freddy spoke carefully, “I mean, Meg, that if you had found yourself in Mildred’s place, married – or as good as married – to this fascinating scoundrel – would you have gone to the police? And given evidence against him?”

No one could have been more surprised than Meg to find that she did not need to reflect on her answer for even a moment.

“Of course I wouldn’t!” she cried. “I’d have kept it dark: I’d have told lie after lie. And if another murder was necessary to help him escape, I’d have committed it with him! There!”

She paused, breathless, astonished at her own vehemence.

Freddy’s eyes were fixed on her with extraordinary brilliance.

“You wouldn’t, of course,” he commented. “When it came to the point, you’d behave like any ordinary, sensible young woman. But it’s pleasant – yes, it’s quite remarkably pleasant – to know that, in your inexperience, you think you would.”

from Uncle Paul (Faber & Faber, £9.99)

—

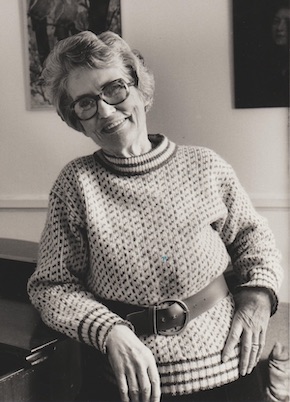

Celia Fremlin (1914–2009) was born in Kent and spent her childhood in Hertfordshire. She then studied at Oxford whilst working as a charwoman. During World War Two, she served as an air-raid warden before becoming involved with the Mass Observation Project, collaborating on a study of women workers, War Factory. Over four decades, she wrote sixteen celebrated novels, a book of poetry and three story collections. Her debut, The Hours Before Dawn (1958; Faber & Faber, 2017), won the Edgar Award. Uncle Paul, first published in 1959 is reissued by Faber & Faber in paperback and eBook.

Read more

@FaberBooks