Passing the acid test

by Tracy Quan I discovered Tom Wolfe’s work in Mummy’s living room. Though I couldn’t understand a word of that electric kool-aid business, I am now reliving it: the allure of a bright blue paperback, holding it in my hands. The sugar cube on the cover looked like something recently soaked in Grand Marnier by my mother, the psychedelic wrapping paper resembling an aromatic flame. And speaking of Grand Marnier, “kandy-kolored tangerine-flake” was equally mystifying. Wolfe’s spelling was almost an affont, for I was reading a grown-up book that year called Freedom – Not License! I took the Not seriously.

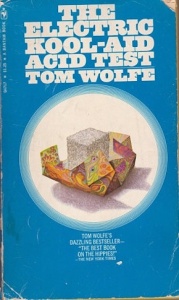

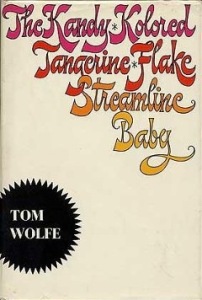

I discovered Tom Wolfe’s work in Mummy’s living room. Though I couldn’t understand a word of that electric kool-aid business, I am now reliving it: the allure of a bright blue paperback, holding it in my hands. The sugar cube on the cover looked like something recently soaked in Grand Marnier by my mother, the psychedelic wrapping paper resembling an aromatic flame. And speaking of Grand Marnier, “kandy-kolored tangerine-flake” was equally mystifying. Wolfe’s spelling was almost an affont, for I was reading a grown-up book that year called Freedom – Not License! I took the Not seriously.

Unable to consider the hallucinogenic lifestyle, I moved on to more down-to-earth material, got preoccupied with books about sex, many of which explained the mechanisms of pleasure, and learned to distinguish prurience from science. I was determined to reach the plateau phase and Tom Wolfe wasn’t going to help with that.

Or so I thought.

When I later encountered From Bauhaus to Our House, I was ready to be distracted from the doctrinaire politics of my late teens. The laughter I experienced reading about 20th-century buildings and ideas made me feel I was consuming a good four-course meal. The house evoked in Bauhaus creates a sense of coming home to the author I didn’t understand when I was small.

Wolfe’s sharp depiction of political infatuation contains a helpful hint, an alternative. Style provides the integrity political and social outsiders need, along with a sense of humour, be it droll or slapstick, in order to survive.”

Wolfe’s witty, humane indictment of modern architecture turned my head. I left the Marxist cult I was involved with, fell into a reactionary mood best understood as 20-something alienation – but I felt emboldened. You could organise your life around aesthetic concerns! What liberation. To escape from that deceptive thicket of class politics was essential, and Wolfe helped me to do so.

During this period, I was introduced to David Durk, a grumpy 1960s liberal (now deceased) who had once tried to reform the New York Police Department from within, igniting the city with his testimony during the Knapp Commission hearings. Despite his disenchanted mien, Durk enjoyed talking about the ’60s, and got me to investigate Tom Wolfe’s fourth book Radical Chic & Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers, published in 1970. He also talked me down from a nihilistic ledge, pointing out that I was trying to be something I could never be: apolitical.

During this period, I was introduced to David Durk, a grumpy 1960s liberal (now deceased) who had once tried to reform the New York Police Department from within, igniting the city with his testimony during the Knapp Commission hearings. Despite his disenchanted mien, Durk enjoyed talking about the ’60s, and got me to investigate Tom Wolfe’s fourth book Radical Chic & Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers, published in 1970. He also talked me down from a nihilistic ledge, pointing out that I was trying to be something I could never be: apolitical.

Inspired by Wolfe’s notions of ‘radical chic’, I showed Durk my earliest political statements about sex work, things I had written in my teens. He was too much a ’60s liberal to buy into my early theories, but the righteous zeal of a radicalised sex worker provoked an empathic cackle of right-on glee. He encouraged me to be an activist again, and I became an organiser with ecumenical tendencies, free to follow my creative impulses.

When sex workers emerged as the new political flavour, I was pleased. And wary. Fashions will change, sometimes to be reviled, even ridiculed, but Wolfe’s sharp depiction of political infatuation contains a helpful hint, an alternative. Style provides the integrity political and social outsiders need, along with a sense of humour, be it droll or slapstick, in order to survive.

While imbibing that non-fiction classic ‘Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers’, I was reading fiction by Colette. The Vagabond, Gigi and the Cheri novels take place in the vicinity of 1900. Her stories about intimate relationships in the demi-monde, depicting a circle of Parisian courtesans, have little in common with Wolfe’s world of contagious American ideas and organised brashness. Somehow the two authors found a way to work together, their judgements and tales swirling around in my notebooks, in my dreams.

While imbibing that non-fiction classic ‘Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers’, I was reading fiction by Colette. The Vagabond, Gigi and the Cheri novels take place in the vicinity of 1900. Her stories about intimate relationships in the demi-monde, depicting a circle of Parisian courtesans, have little in common with Wolfe’s world of contagious American ideas and organised brashness. Somehow the two authors found a way to work together, their judgements and tales swirling around in my notebooks, in my dreams.

From this urban stew, my fictional diarist Nancy Chan was born, along with her comic dilemmas. She is a turn-of-the-21st-century New York call girl clinging to the safety of realpolitik. Nancy’s encounter with radical ideology is drawn from life, but the activist plot running through her diaries is deeply informed by Wolfe’s critique of the evolving aesthetic we now call radical chic.

It began, however, with a child’s uncomprehending aversion to The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, a memory I did not fully appreciate until I learned of Tom Wolfe’s death.

Tom Wolfe (1930–2018) was the author of more than a dozen books, among them The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, The Right Stuff, The Bonfire of the Vanities, A Man in Full, I Am Charlotte Simmons and Back to Blood. He received the National Book Foundation’s 2010 Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters.

Tom Wolfe (1930–2018) was the author of more than a dozen books, among them The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, The Right Stuff, The Bonfire of the Vanities, A Man in Full, I Am Charlotte Simmons and Back to Blood. He received the National Book Foundation’s 2010 Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters.

Tracy Quan is the author of three novels, including Diary of a Manhattan Call Girl. Her poetry has been published by the Los Angeles Review of Books and Poets Reading the News. Her latest show Gershwin Live: The Vinyl Forest is at The Lounge at Dixon Place, New York on 8 June.

More info

@TracyQuanNYC

Author portrait © Circe Hamilton