At the funeral

by Oskar Jensen

‘WE THEREFORE COMMIT her body to the deep …’

Leyla Moradi started in surprise. Admittedly, she hadn’t attended many Anglican funeral services, but something about the wording seemed a bit off.

‘… to be turned into corruption, looking for the resurrection of the body, when the sea shall give up her dead…’

She risked a glance around. No, it wasn’t just her: most people were looking a little disconcerted. And that was definitely grass beneath her feet, the only waves the motion of the trees, rippling in a light spring breeze. At her side, Torben gave a discreet cough, and she refocused.

‘… and the life of the world to come, through our Lord Jesus Christ who at his coming shall change our vile body, that it may be like his glorious body, according to the mighty working whereby he is able to subdue all things to himself…’

‘I was talking to the chaplain beforehand,’ Torben whispered to her in the next pause. ‘Turns out that Charlotte found a loophole in the order of service. Apparently she’s always quite liked the trappings of being buried at sea’ – Leyla glanced down at the body in the grave, stitched inside a sailcloth cocoon – ‘and she even had the cannonballs, a gift from some marine archaeologist she once met in New Orleans. See, they’re weighing down either end. So, when she found out she couldn’t have her ideal option—’

‘Ssh!’ said someone.

‘Sorry,’ they both said, automatically.

Leyla was quietly impressed. She’d never met Dame Charlotte – until a few months ago, Leyla hadn’t even seen Torben in a decade – and was only here because he had asked her. It took quite a lot to drag her as far north as East Finchley, but these woodlands and their ancient gravestones were really rather magnificent, and she’d rarely seen such a crowd. OK, seventy-three wasn’t old, but Torben said Charlotte had no family to speak of, only second cousins or removed cousins, Leyla never knew which was which, which meant that most people must be here because they cared. And there were hundreds of mourners of all ages, almost all of them adhering to the dress code on the invitation – ‘any colour, so long as it isn’t black’ – many of whom looked surprisingly, well, chic.

Maybe it was because the deceased had become something of a minor celebrity in environmentalist circles, in recent years. Even Leyla’s work as a barrister representing campaigning charities had brought up the name of Dame Charlotte Lazerton more than once.

Or just maybe, she thought, looking up at the tears streaking Torben’s face, it was because she had been a genuinely good person, whom people loved. Such things were possible, after all.

‘Ach, for helvede, but at least that’s over,’ said Torben, as the service concluded and the throng began to break up. His face was still glistening, but he didn’t seem to care. Leyla had a handkerchief, a silk Liberty one in a nod to the dress code; part of her wanted to take it out and—

‘Well, come on, Leyla, cheer me up,’ he said. ‘I haven’t dragged you ten kilometres out of town so you can be all deferential and respectful of my grief. If I wanted sympathy, I’d’ve asked Ruth.’

Harsh, thought Leyla. But also undeniably fair. She glanced around for inspiration. ‘See that woman over there? I hear she’s buried nine husbands,’ she said, in a music-hall sort of voice.

‘A gold digger?’ said Torben.

‘No, a grave digger: she’s a sexton.’

Torben groaned.

The point is, it was just her and Mortimer, her Irish wolfhound, in the house. Dogs that size, they take a lot of feeding, and of course, he couldn’t get out, so…”

‘I had to improvise, OK?’ said Leyla. They were allowing themselves to drift with the tide, back towards the cemetery gates. There was some sort of reception planned, organised by the Academy of Western Art in lieu of a family gathering, back in the centre of town.

‘So,’ said Leyla. ‘You said she couldn’t have her ideal choice of burial…?’

‘Ugh,’ said Torben. ‘Well, no. You see, what she really wanted was to be… to be fed to the tigers at London Zoo. They’re Sumatran tigers, critically endangered; she said she wanted to do her bit.’

‘Ah,’ said Leyla. ‘I suppose the keepers aren’t keen on giving their charges a taste for human flesh.’

‘I think it was more a health and safety issue,’ said Torben. ‘The average human body nowadays contains so many dangerous chemicals that…’ His voice trailed off.

‘Sorry,’ said Leyla. ‘Too soon? Too much?’

He shook his head. ‘Unfortunate coincidence. They kept this bit out of the eulogy, obviously, but, when they found her… you see, she’d been lying there for some time, several days maybe…’

‘A fall, wasn’t it?’ she said softly. He had told her before that the body had been found at the foot of the stairs.

Torben grimaced. ‘So it seems. The point is, it was just her and Mortimer, her Irish wolfhound, in the house. Dogs that size, they take a lot of feeding, and of course, he couldn’t get out, so… well, the way the policewoman put it was that he’d “had a little nibble”.’

Torben looked like he was going to be sick.

‘I’m so sorry,’ she said. Side by side, her hand was very close to his. A simple matter to reach out; to squeeze it. Should she—?

‘Torben!’ came a voice from behind them; they both turned. A formidable-looking woman of middle years was advancing on them.

‘A tragedy,’ the woman said.

‘Perhaps,’ said Torben, reassembling his features. Now what on earth did he mean by that? ‘Oh – Carmen Sabueso, Leyla Moradi,’ he managed. ‘Carmen edits the art history list for OUP,’ he went on. ‘She commissioned my book on Friedrich.’

Ah. This was shop; Leyla sensed power. Better play along for Torben’s sake. ‘I loved it,’ she said, ‘which always confused me – now I know who to actually credit.’

Sabueso smiled – the sort of tight-lipped smile people allowed themselves at funerals. ‘Well, Charlotte had already done such a good job licking him into shape,’ she said. ‘Speaking of which, Torben, I have a new series, Art Historiography in the 2020s – shortish, accessible editions, around sixty thousand words, profiling seminal figures of our times – naturally the world needs a volume on dear Charlotte, and you were my first thought.’

Leyla started. Was this how publishing worked? The body barely in the ground five minutes, and already getting down to business…

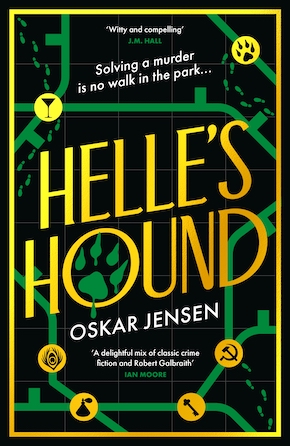

from Helle’s Hound (Viper Books, £16.99)

—

Oskar Jensen writes crime, literary, historical and children’s fiction, as well as non-fiction focusing on the history of song and street culture. He read his three degrees in History at Christ Church, Oxford, before taking up postdoctoral fellowships in London and Norwich. In 2023 he was shortlisted for the Wolfson History Prize. A NUAcT Fellow at Newcastle University, he makes regular appearances on BBC Radios 3 and 4. His debut adult novel Helle & Death, the first Torben Helle mystery, was published by Viper Books in 2023. Helle’s Hound is out now in hardback, eBook and audio download.

Read more

oskarcoxjensen.com

@oskarcoxjensen

@ViperBooks

Author photo by Chloe Rosser

Also by Oskar Jensen:

Top tens: Locked room mysteries