Be a writer

by Toby WilkinsonIn Ancient Egypt, or at least in the New Kingdom, writing was taught in scribal schools. Young boys (there is little evidence for girls’ schooling) were taught to read and write by dictation and by copying existing texts. Various compositions, of different genres and from different periods, were deemed suitable for teaching purposes. Classics of Egyptian literature, such as ‘The Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor’, were used alongside letters, hymns and more mundane lists of words. Teachings were a favourite category of text for copying practice, since it was hoped that their moral message would help mould the character of the young scribes even as they learned to write. Many of the best-known teachings therefore survive as scribal copies, complete with the students’ copying errors and mistakes of comprehension. Students’ exercise books – rolls of papyrus – might contain copied texts of many different genres, side by side.

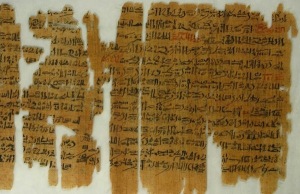

A Ramesside papyrus in the British Museum (10684), known as Papyrus Chester Beatty IV, is a typical example. One side is inscribed with hymns while the other side contains a group of instructional texts, including an exhortation to ‘Be a Writer’. Unusually, this work goes beyond the usual praise of the scribal profession by suggesting that only writings confer true immortality, because men’s bodies and tombs turn to dust. Scepticism about the afterlife, first expressed in the harpist’s song from the tomb of King Intef, is rare in Egyptian writings; here it reaches its logical, extraordinary conclusion. To emphasize the point, the text mentions the famous authors of the past whose names endure. This is also remarkable, since the tradition of authorial attribution was almost unknown in ancient Egypt; most texts were deliberately anonymous. In several respects, therefore, ‘Be a Writer’ is radical work, suggesting that the schooling of scribes was not, perhaps, as traditional or stultifying as it might appear.

The work is inscribed in twenty horizontal lines and is divided into sections/stanzas by rubrication. It is composed in an orational style, to be recited aloud, and shows evidence of metre. Fittingly, the copy preserves a number of scribal errors.

Man perishes; his corpse turns to dust; all his relatives pass away. But writings make him remembered in the mouth of the reader.”

Now if you do this, you are skilled in writing. As for those wise writers from the time after the gods, they who foretold what was to come, their names have become everlasting, (even though) they have departed this life1 and all their relatives are forgotten.

They did not make for themselves mausolea2 of copper with tombstones of iron;3 they did not think to leave heirs, children to proclaim their names: (rather) they made heirs of writings, of the teachings they had composed.

They gave themselves [a book4] as (their) lector-priest, a writing-board as (their) dutiful son. Teachings are their mausolea, the reed-pen (their) child, the burnishing-stone5 (their) wife. Both great and small are given (them) as their children, for the writer is chief.

Their gates and mansions have been destroyed, their mortuary priests are [gone], their tombstones are covered with dirt, their tombs are forgotten. (But) their names are proclaimed on account of their books which they composed while they were alive. The memory of their authors is good: it is for eternity and for ever.

Be a writer, take it to heart, so that your name will fare likewise. A book is more effective than a carved tombstone or a permanent sepulchre. They serve as chapels and mausolea in the mind of him who proclaims their names. A name on people’s lips6 will surely be effective in the afterlife!7

Man perishes; his corpse turns to dust; all his relatives pass away.8 But writings make him remembered in the mouth of the reader.9 A book is more effective than a well-built house or a tomb-chapel in the West,10 better than an established villa or a stela in the temple!

Is there one here like Hordedef? Is there another like Imhotep? None of our kin is like Neferti or Khety, their leader. May I remind you about Ptahemdjehuty and Khakheperraseneb! Is there another like Ptahhotep, or the equal of Kairsu?11

Those wise men who foretold what was to come: what they said came into being; it is found as a maxim, written in their books. Others’ offspring will be their heirs, as if they were their own children. They hid their magic from the world, but it is read in their teachings. They are gone, their names forgotten; but writings cause them to be remembered.

NOTES

1. Literally, ‘they have departed having completed their lives’.

2. The Egyptian term indicates the visible part of a tomb, a mud-brick edifice shaped like a steep-sided pyramid.

3. The Egyptian term for iron translates literally as ‘miracle of heaven’, indicating that the Egyptians first encountered iron in its meteoric form.

4. Here and elsewhere in this text, the term for ‘papyrus roll’ has been translated as ‘book’.

5. Used to prepare papyrus as a writing medium.>

6. Literally, ‘in the mouth of the people’.

7. Literally, ‘necropolis’.

8. Literally, ‘return to the earth’.

9. Literally, ‘reciter’.

10. i.e. the land of the dead.

11. This paragraph recounts the names of famous men to whom the Egyptians ascribed exemplary works of didactic literature or other great achievements of learning.

From Writings from Ancient Egypt

Toby Wilkinson is an English Egyptologist and academic. He has been a Fellow of Clare College, Cambridge since 2003. He is the author of numerous books including The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt (2010), which won the Hessell-Tiltman Prize, and The Nile (2014). Writings from Ancient Egypt, translated and with an introduction by Toby Wilkinson, is out now in Penguin Classics. Read more.