The bear

by Kieran DevaneyThere was a bear. Life in the woods, where he lived with the other bears, had begun to sicken him.

The bear would go to the edge of the forest and watch the people who lived in the small town below. The stature of the buildings, the play of light on glass, the swish of fabric on pink, hairless flesh: these all moved this bear and he began to yearn. This was a bear that yearned.

On a cool night, this bear leaves the woods and enters the town. He breaks into a barber’s and uses an electric shaver to remove all his fur, leaving just a small clump on the top of his head. The bear then breaks into a hardware store and, with a file, pares his claws until they are flat and dull. Finally, this bear steals the biggest shirt and pair of jeans he can find and strains them over his massive frame. On this night, looking at his reflection in the flat black glass of a shop window he begins to feel better. It is in this way that this bear becomes a man.

…

The bear is in the office. He is in front of his computer. He clicks one window open and looks at the number in it. He clicks open another window, moves his mouse into one of the blank fields and types in the number. He moves the mouse and clicks a button and the screen refreshes to reveal the field blank again. The bear switches windows again and looks at the number. He clicks open another window. He moves his mouse. He runs his claws through the coarse scruff on top of his head. He gets up. He goes to the toilets and enters a stall. He puts his head against the cold formica side panel. He feels his sinew stir. He shuts his eyes. There is so much of the day left.

…

The bear is in the pub with his girlfriend’s father. It had been intended for it to be just the two of them, but when they get to the pub, they run into two of the father’s friends. The father is a dentist. He is a man and he has a big pink face. His friends, likewise. The dentist is called Clive. The dentist puts his drink down and, looking at the bear, he begins to speak. It’s a fucking gamble being a dentist. Here. Distracted, the dentist points at the folded paper in the bear’s bag. You on the crossword? Here you go… Two down, Flaubert, easy. The dentist picks up the paper and starts filling in the clue with angled capitals. Flaubert is incorrect. The bear, drinking his drink, looks at the dentist. Fucking gamble, as I was saying. I had this girl in a few days ago, I seen her a few times before, she was just in for a checkup. Beautiful teeth she had, not a thing wrong with them. Anyway, I’m poking around and, uh, the dentist picks up his pint and swigs from it, he then cocks the pen which he still holds in the direction of the bear. His friends follow the pen with their eyes. They have pork-scratching skin and bad breath. She’s lying on the chair, just there like where you are now and I’m having a go in her mouth, y’know, when I notice that her skirt – it was a short skirt, floaty sort of material – has ridden up. This is the gamble, because, she’s lying there with her mouth open, eyes closed, but the position of her hands, it almost looks like she’d done it on purpose. You know, pulled the skirt up? The dentist sits back and drinks. The bear drinks. Shit, man. What did you do? goes one of the two friends. It is very loud in the pub. The dentist leans in; he is still looking at the bear. He has an incredulous look on his face. He turns to the guy, then he turns back to the bear, still with the incredulous look. What the fuck do you think I did, Andy? Andy shrugs. Fuck all, is what I did. That’s the gamble. Sometimes you do, sometimes you don’t. What I generally do, if it happens more than once – that’s the clue – I rest a hand gently on their thigh as I’m working, gauge the response and go from there. But like I say, it’s a fucking lottery. Pick the wrong numbers and you could land up in court, in jail, lose your job, lose your wife and kids. You got to play the system. You got to have rules. He grins at them one by one. Fuck, goes Andy. Fucking hell. The dentist drains his pint and looks down the glass, surprised that there is nothing left in it. He turns the paper onto the back page and runs his eyes over it. The bear feels itchy under his clothes. It is so loud in there. Another drink? the dentist asks and they all nod. He goes to the bar.

…

The bear is in the men’s. He is at the urinal. He looks ahead. His frame is vast and his centre of gravity is low. From behind the walls comes the noise of water moving through pipes. All the stalls are occupied. The bear can see feet under the walls of the nearest one, black trainers, soles turned inwards. On the other side of the bear, the door opens. A man comes in, he glances at the bear. He looks over at the stalls, he sees they are all occupied. He comes and stands next to the bear and undoes his jeans. The man pulls his dick out. The man spits into the urinal trough. The bear looks ahead. He feels the man turning to look at him, he feels that. He continues to look ahead. The water moves through the pipes and there is noise. The men’s is of an older design. The urinal is one long trough, with semi-cylindrical tiles sloping down to one metal grate. The trough is set slightly below the floor, the lip of which is made of brown tiles.

As soon as the bear entered the world, there was work. To live in the world is to owe something. If the bear had known this, would he have made the same decisions?”

The rest of the floor has grey tiles. There are small rectangular windows high up; the glass in them is yellow. The bear has no notion of what those windows would look out on, if you could climb up, if you could see through the yellow glass. He has no notion of where in the building he is. The man is not going, he isn’t pissing. The bear glances down at him. Ugh, says the man, and then shortly afterwards he says, Ugh. He gives a sigh. He looks at the bear. He is shaking his head. I can’t go, he goes, I can’t go while you’re here. He steps away from the urinal, turns and does up his trousers. He goes to the sink and rinses the tips of his fingers. He dries his fingers on his jeans. He leaves the room. The bear finishes and goes to wash his hands.

…

As soon as the bear entered the world, there was work. To be human, it seemed, there had to be work. To have the things that defined people, you had to have the money to afford them, and to have that, you had to work. Similarly, work itself defined people. When he found work, the bear was surprised at how much time it took up. Though less complex, his society among other bears had not been founded on the principle of work – when they had enough to eat, when they had done what was necessary, they stopped and were leisurely.

Working in an office, he could finish all the necessary tasks and then ask his manager what to do. The manager, always hassled, always put upon, would sigh at the bear. He had been working too fast again. Then he or she would find some filing for the bear to do, or some tidying up, or some¬thing. Alternatively, there would be nothing to do, but even in those situations the bear was not free to leave the office. He had to sit there and look at the screen of his computer, look busy.

The bear could not comprehend fully the logic of this and it got him down. It seemed as though work was not so much something that you did, as a place you went to and stayed at for a set period of time, whether there was anything to do or not. It was rarely made clear to the bear, as he went from temp job to temp job, exactly who he was working for, or who he was making money for, or how his filing or data entry fitted into a larger schema. There was never time for the managers to explain that. Or perhaps they too were unaware. On the bus in the mornings, the bear could see the dark pull that work exerted on the shrunk-pink faces that rode with him.

The problem for the bear is that he cannot simply return to the woods if no longer satisfied with life among humans. He cannot simply quit. To be human is to acquire debt. And debt must be paid back, and debt accumulates. Unless you are one of the fortunate few hundred in the world to whom debt is paid, then you must pay it. To abscond is not conceivable. Were the bear to let his fur grow back and return, naked to his brethren, he would be chased down and made to pay. He would be put back into work. To live in the world is to owe something. If the bear had known this, would he have made the same decisions?

…

A friend of the bear’s has been going on for ages about visiting the zoo, so one weekend he agrees to accompany her. The bear hulks along among the cages. It’s cruel, don’t you think, to see them cooped up like this? They look so sad, says Lisa. They are looking at a cage with a leopard in it. The leopard is asleep in one corner. She turns and looks at him and the bear looks back at her. Something passes between them. She turns away and begins to walk towards the giraffe enclo¬sure. The giraffe is standing and looking pensively at the trees on the hill above the zoo. The bear, too, stands and looks at the trees. He begins to follow her. She has stopped in front of the giraffe. This is fun, she says, turning to the bear. The bear looks at the giraffe, which continues to look at the trees. It is cold. The giraffe looks like it has patches of rust on it. It is dirty, it is fat, its teeth are horrible. Its legs looks spindly, it does not seem to understand its cap¬tivity, it continues to strain its neck while it looks over at some trees. Being winter, the trees on the ridge are just bare branches. The enclosure is four brown walls, a brown floor and brown hay in a corner. There are pools of brown water on the concrete and piles of black giraffe pellets in the pools. This giraffe is called Terry, he was born in the zoo and is now fully grown, Lisa reads from a sign on the wall.

When they see the spiders, especially the tiny brilliant black widow, which is moving, the bear grows jumpy and agitated. He begins to scratch his skin all the time, feeling constant itches and the presence of insects.”

Inside the reptile house, with the bright staring eyes of frogs and the lethargy of the snakes, the bear gets too hot, has to leave and sit down outside. His breath, big in the air, comes in grey plumes. Are you all right? Lisa puts the back of her hand on the bear’s forehead, on skin that feels scrubbed hard and is pink. The bear looks up at her. He puts his hands on his knees and pulls himself up with effort. He looks down at her.

When they see the spiders, especially the tiny brilliant black widow, which is moving, the bear grows jumpy and agitated. He begins to scratch his skin all the time, feeling constant itches and the presence of insects. Out of the corners of his eyes he is sure he keeps spying movements.

They go to the penguin enclosure. It is noisy there, there are quite a few families. I’ve never liked penguins, says Lisa, I’ve always found them bizarre. There’s something weird about them. I don’t know, I think I associate them with death. Isn’t that weird? Animals in general I’ve always associated with death. Penguins in particular but animals in general, I guess. I suppose it’s the way they approach death, you know. They don’t think about it. They spend their whole lives avoiding it, but just by instinct. It’s only because that’s all they know that they don’t just die straight away. But then in some ways, we’re the same. I mean people. We know just enough to think about it, but we still act the same, we don’t know enough to rise above that. I’ve always been sad that people aren’t smarter, you know. Like when you see films on the TV or read a book about an alien civilisation and they’re always so civilised and advanced and intelligent. It seems like we have the worst luck really. We’re too clever not to be aware of what we are, but not clever enough to live together properly. She looks up at the bear. Just then, a kid drops a toy, a die-cast metal car, into the enclosure. The penguins cluck and shriek and jump back towards the corner. Lisa makes a face. I don’t like penguins. Can we go? she says.

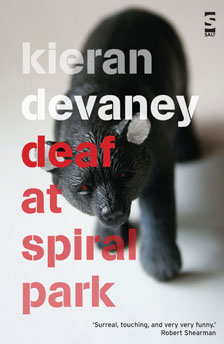

From Deaf at Spiral Park, published by Salt Publishing. Read more.

Kieran Devaney was born in Birmingham in 1983. He has worked as a library assistant and an academic support worker. He writes davidcameron.tumblr.com and a fake celebrity twitter account. He is writing his second novel, about a dog of infinite size, in Brighton, where he currently lives.

Cover image © John Oakey