Berlin by twilight

by Mika Provata-Carlone

“An absolutely epic book. A walking remembrance.” Walter Benjamin

“Who in all the world goes to Berlin voluntarily?” wrote Joseph Roth in The Wandering Jews in 1926–27. For him, as for so many others who were acutely attuned to the particular dissonances of a global order in turmoil, Berlin represented the metaphorical and real space of a harrowing existential predicament: the new paradigm for a world in disharmony, displacement, dissolution, the emerging theatre for a new politics of might and hatred, for a rhetoric where words became all-engulfing vortices of total domination and ruthless annihilation. More pragmatically and realistically, Berlin was the shore where the remnants of a Jewish humanity in tatters washed off from the East – to stumble onwards to some ill-defined terminus or just simply die.

Yet for others, Berlin in the 1920s, during the years of what may now seem the utopia of the Weimar Republic, Berlin was the epicentre of a fertilising chaos promising new creation: following a catastrophic beginning for Germany, the twentieth century, as it emerged in the streets, cafes, lecture halls, artists’ studios, stages, factories or laboratories of Berlin, had a uniquely mesmeric allure. Few cities around the world at the time could claim such a consortium of minds reflecting on the future of humanity, on the cosmos and its workings, or on a technological progress that would bring release from the more pressing conditions of existence; few places could pride themselves on a similar plethora of responses, prophetic, critical, apologetic or outright jubilatory towards the smallest or the greatest traits of modernity; perhaps nowhere were there schools of thought bringing together so systematically, determinedly and audaciously intellectuals and creative professionals, businessmen with visions of grandeur which became magnificent acts of public patronage, all of which has left its indelible trace even onto our own similarly metamorphic present.

Walking in Berlin is an utterly engrossing, fascinating ‘walk-along’ guide to a Berlin that did not last for very long – or perhaps hardly existed at all.”

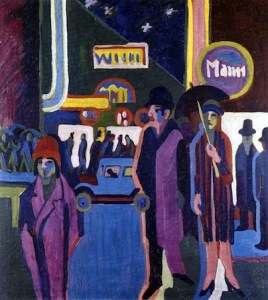

Berlin in the 1920s is the triumph of neo-Prussian order and decorum, but it is also a time of unprecedented tolerance, inclusiveness, a space where voices can be heard and even reverberate. Einstein, Heisenberg or Max Born deconstruct the cosmos to its most infinitesimal particulars, Carl Jung, Erich Fromm, Karl Manheim, Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer, Herbert Marcuse, Edmund Husserl or Ernst Cassirer and Walter Benjamin ponder its socio-political and eschatological significance, whereas Fritz Lang, Erich Kästner, Kurt Weil and Berthold Brecht, Gropius and Mies van der Rohe, the Neue Sachlichkeit painters like George Grosz, Otto Dix, Max Beckman or Adolf Dietrich, together with the Bauhaus architects, seek to give that world a tangible, everyday dialectics, an aesthetic identity, an urban beauty. They all frequent the streets of Berlin, its cafes, parks and public buildings. They thrive and clash, give birth to a very specifically Berliner cosmopolitanism that will attract a cohort of anxious celebrity foreign souls, such as Auden, Isherwood or Spender.

This Berlin of miraculous attraction is the subject of Franz Hessel’s Walking in Berlin: A Flâneur in the Capital, originally published in 1929. It is an utterly engrossing, fascinating ‘walk-along’ guide to a Berlin that did not last for very long – or perhaps hardly existed at all. As Hessel writes, Berlin is “a city that’s always on the go, always in the middle of becoming something else”; to know its past and its present, one must first explore its future, the urban landscape feverishly being planned for the new global metropolis, that especially ominous blend of “old architectural horrors and new solutions and redemptions”. Walking in Berlin is written in the flippant language of flappers, with a serious, sharp, deeply erudite twist, and in a vacant omniscient first person, the flâneur, as Walter Benjamin, a close friend and literary collaborator of Hessel, would call that all-curious leisurely gentleman, observing, attesting, evoking, above all hinting and revealing unexpected wonders or well-hidden miasmas.

Weimar Berlin is a city of penetrating contrasts, whether it is between its huge unemployment rate and the dazzling luxury lifestyle of its middle and upper classes, or between its rigorous conservatism and its startling liberal-mindedness. Hessel seemingly aims to write the twentieth-century Baedeker, also a German product that had first appeared a hundred years previously: a guide that will bridge the past, its awesomeness and tranquil or brutal monumentality, with a modernity in explosive flux. We feel that we have walked on every street and suburb of Berlin by the end of our peregrinations, that we have paid tribute to every monument and indulged in every new temple of pleasure or quite possibly wisdom. As a historical record of what was there, Hessel’s book is invaluable for the details it provides, but also for the atmosphere that it conjures of that so very semantically charged moment in time. It is unique, especially, for what it leaves unsaid, for what it begs us to see behind opaque parapets or hear behind sentences that can only allude or intimate in hushed tones what under different circumstances, or in another’s narrative, would have been bold statements, stark illustrations, true verbal panels of new objectivity.

Hessel begins with deceptive lightness: we are introduced charmingly to the “terrifically merry classes” and explore the business of leisure and salon society, where “bedlam” (jazz) and “elegant limits” (the bourgeoisie) converge to produce the new breed of “the ambitious Berliner”. Next we are asked to admire the perfect, unwasteful efficiency of machine technology, industry and progress in “reverent shrines of fervour”, the urban miracle and the rebirth of a nation, as well as Prussia past and present, the historical and ideological skeleton of this new reality. The architects and artists who built Berlin, the political figures who ruled it, the merchants and businessmen who financed it, the tradesmen and craftsmen who gave it life and the folklore characters who cast a spell on it, lure the reader along a romping tour and journey, where historiography and landscape descriptions mingle with fiction. Walking in Berlin is as much a traveller’s guide to a lost world of great, mixed wonder, a novel where the characters are real or imaginary people, statues and buildings, landscapes and an almost transcendental sense of place, but also a record of human history as an urban experience, a specifically Berlin experience. Above all, it is a declaration of presence and of a possible alternative vision.

Critics have often stressed Hessel’s failure to expose the underbelly of this new state, the socio-economic crisis and the bleakness that followed it, the emerging culture of racism, hatred, violence and decadence that would become the subjects of Kästner’s Fabian (1931), Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927), Brecht’s Threepenny Opera (1928), Der Blaue Engel (1930) or Döblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz (1929). It is true that throughout Walking in Berlin we find no blaring accusations, no weighty social analysis or critical denunciation, no sinister noir pages, nor do we find a vocal appraisal of what would perhaps be a natural subject for Hessel himself, the presence, legacy, contribution of Jewish culture and industry to Berlin history, to its character and development.

The architecture of might and perfection that Hessel sardonically admires, and the new society of luxury, frivolity and thrill, will provide ample cover for what lies and grows beneath.”

Yet it would be unfair to thus limit our reading of Walking in Berlin. Hessel’s tone may seem light-hearted, suavely polished and suited to ears used to the delicious sounds of new slang and lounge-lizard nonchalance, yet his voice has a lucidity that will entice even the most unsuspecting readers to look at the slums of the almost dismantled Jewish neighbourhood which is to be replaced by a fantastical blueprint of metropolitan achievement, or to the river where the corpse of Rosa Luxemburg was thrown and found, to the ghostly presence of Jewish writers, artists, thinkers, public figures, especially of Rahel Varnhagen, throughout the city’s inner spaces and brightest minds. Hessel speaks loudly of Prussian perfection and aspiration, yet he also whispers all that may not be safely spoken. His pages begin to whirl in a stroboscopic panorama of highlights and lowlights of Berlin life. As with other semi-fictional works where Berlin is the main character, the underpinning metaphor is the unstoppable inertia of mad speed, coltish modernity, invincible progress – their ominous inevitability. Words begin to feel like the dots on Paul Signac’s portrait of Félix Fénéon, an enthralling as well as ominous hallucinatory potion, even at its most tongue-in-cheek, its most flippantly elegiac moments of whimsical irony. Lang’s Metropolis is a spectre of each image and paragraph, and prophetically, whether consciously or unconsciously, the spiralling dream of the ultimate urbs hints at what is to come: amazons will become murderous Valkyries, machinery will dominate as it kills, efficiency will remove not only the toils of the factory hands but also the human element from every proposition. The architecture of might and perfection that Hessel sardonically admires, and the new society of luxury, frivolity and thrill, will provide ample cover for what lies and grows beneath.

1929 may seem a year that is relatively removed from the nightmare that was to follow, and yet all has already begun: Berlin is the first city where the presence of brown shirts is felt, the first success in Hitler’s experiment of propaganda and intimidation. Berlin was considered dangerously avant-garde, too free, too much of a risk for what is afoot. In 1926 Hitler will appoint Joseph Goebbels as the Gauleiter (regional party leader) of the city and Berlin will become the training ground for Germany’s Nazi future. The first persecutions, racist harassment, the normalisation of public bullying, they all happen before everywhere else in Berlin. In 1929 something equally astonishing happens, and Hessel’s book should perhaps be seen as its companion piece: the Jewish community in Berlin which numbers about 160,000, decides to publish an inventory of all its members, a Jewish Address Book of Greater Berlin. In the preface of its re-issue in 1931–32, the aim is explicit: it is a response to the vile anti-Semitic attacks in the press, in everyday public and private life, to the toxic change in the nation’s ethics and social fibre. The Jewish Address Book is a j’accuse against the “hard time faced by German Jewry” and an “I will not budge”, “I shall not assimilate or flee”, in unsettlingly Germanic, monumental typeface, an act of self-confirmation in response to Goebbels’ propaganda, to the rise of a power pledged to bring total destruction. With satanic irony, this act of resistance may have well been the ultimate act of unwilling collaboration: here was a reliable, exhaustive list for the future ‘cleansing’ of the city of its Jewish human capital, so that Goebbels could triumphantly proclaim it judenrein in 1943.

Hessel’s book is a similar, if more subtle gesture of non-erasure as well as of disapproval, of the flâneur as the detached, yet profoundly involved, outsider: as he contemplates the modernisation of part of the city, his reaction is that “another piece of our lives would fade to pale memory”; elsewhere he warns us of the “conflict between the neutral modern organisations and the personal engagement demanded by spiritual objects”. Hessel’s Berlin is a determined effort to freeze time, to stop the unstoppable, to mark, like the Jewish Address Book, everything that made the city beautiful, livable, tolerant, admirable. By juxtaposing this ideal beauty and history to intensely dense, unsentimentalist descriptions of slums, the homeless, the less savoury sights of Berlin by night, the impeccable cleanliness of the streets with its unmistakable sinister echoes, Hessel completes Joseph Roth’s What I Saw: Reports from Berlin 1920–1933 with an audacious, if delusional, might-have-been, a projection of timelessness and possibility into a future of painfully evident darkness.

Walking in Berlin can be read lightly as a postcard from the past; it should be read seriously as an inexhaustible record of all that Berlin was and might have been, as an enthralling guide to a wealth of references, sidetracks, lost paths. Evokingly translated by Amanda DeMarco, and beautifully published by Scribe, this is a first encounter with the myth and the reality of that intangible fantastic beast of a city.

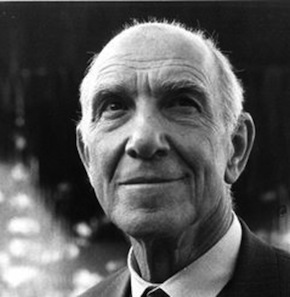

Franz Hessel was born in 1880 to a Jewish banking family, and grew up in Berlin. After studying in Munich, he lived in Paris, moving in artistic circles in both cities. He co-translated Proust with Walter Benjamin, as well as works by Casanova, Stendhal, and Balzac. His relationship with the fashion journalist Helen Grund was the inspiration for Henri-Pierre Roche’s novel, and later Francois Truffaut’s film Jules et Jim. He died in early 1941, shortly after his release from an internment camp. Walking in Berlin, translated by Amanda DeMarco, is published by Scribe in hardback at eBook. Read more.

Franz Hessel was born in 1880 to a Jewish banking family, and grew up in Berlin. After studying in Munich, he lived in Paris, moving in artistic circles in both cities. He co-translated Proust with Walter Benjamin, as well as works by Casanova, Stendhal, and Balzac. His relationship with the fashion journalist Helen Grund was the inspiration for Henri-Pierre Roche’s novel, and later Francois Truffaut’s film Jules et Jim. He died in early 1941, shortly after his release from an internment camp. Walking in Berlin, translated by Amanda DeMarco, is published by Scribe in hardback at eBook. Read more.

Amanda DeMarco is an editor, translator, and the founder of Readux Books. Originally from Chicago, she is currently based in Berlin.

@DeMarcoAV

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.