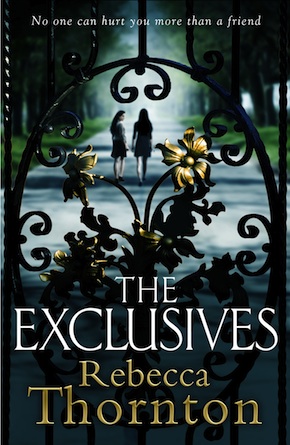

Behind the black gates

by Rebecca Thornton

“Utterly gripping.” Esther Freud

When I wrote my novel The Exclusives, a psychological thriller set in a boarding school, recollections of my own school days played some part in underpinning themes of the book.

I was sent to a boarding school when I was thirteen. One of my overriding memories of the place is the school gates. They were tall and black, and shone in the sun. Despite their beauty, I found them pretty frightening; the metal structure looming down on me like a heavy, shadowy presence.

As my Father drove through them for the first time they shut behind us, locking out the rest of the world.

I said goodbye to my parents, bidding them farewell with a dismissive wave and a smile. After all, there was a bunch of girls watching.

“It’s OK,” said the housemistress to my mother and father. “She’ll be fine.” She pulled me aside a few seconds later:

“Let these girls take you to lunch. And just so you know, you aren’t allowed to call home. For three weeks. So you don’t feel homesick.”

All I could manage, was an “Oh” and a “thank you.”

And thus, with these words, it was set: it didn’t matter how I felt. All would be fine, and that was it. “Be courageous” was the gloss. Underneath though, the subtext was that despite feeling sad and lost, I would be expected to put on my best smile, marching forward in the correct school manner.

In Fide Vade was our school motto: Go in Faith. But many of us didn’t have much faith – in ourselves, at least. We were fragile and our senses of selves precarious, propped up only by the rigidity and structure of the school rules. I’m not alone in thinking this. When I talk to many other girls who went to boarding school, they say they felt the same.

All of these real-life dynamics fused together to allow me to explore the fictional lives of my characters.

Their fragility meant they would react to certain events in a more visceral way than others perhaps might. Josephine and Freya, the two main girls in the book, do exactly this. When a night out goes horrendously wrong, they react in totally different ways, which impacts the rest of their lives. But they had one thing in common – they were two emotionally vulnerable teenagers, lost in the art of growing up.

I remembered how the girls at school used body language as a weapon; the nuances and intensity of female friendship; the multitude of narratives, both light and dark, being spun by the pupils from an innocent conversation.”

In a first, lazy attempt at writing my novel, I tried to base one of my main characters on a fellow pupil I once knew. It didn’t work. She kept getting in the way of the plot, stopped my imagination from flying so I scrapped her. I had to work to find inspiration elsewhere. One of my main characters – Verity, the Deputy Head girl in the novel – she exists, somewhere, although I have no idea where and I doubt I’ll ever see her again. I was scrolling through Facebook once, when I caught sight of a girl on someone’s newsfeed. Instantly, I knew she was meant to be Verity. So, although she is based on the physical appearance of a real person I have no idea of her real-life character. I don’t know about her likes, dislikes and affectations. None of that. But when I wrote about Verity, I kept the image of this Facebook girl in my head: smug, curly-haired and for some inexplicable reason, so annoying. And when I imposed my own imagination on to her, she revved up the plot, behaving in ways in which I detested.

Ideas for the novel would also swing into play when I remembered how the girls at school used body language as a weapon: the light resting of a hand on a desk which said, so boldly, you are not welcome to sit next to me; the nuances and intensity of female friendship; the multitude of narratives, both light and dark, being spun by the pupils from an innocent conversation.

It was the collision of experienced feelings and imagination that crystallised the story. The book is all fiction, yet there were certain memories, imprinted onto my subconscious, that helped fuel empathy for what I put my characters through. Watching a girl’s real-life reaction, for example, when she found out about a rumour about herself – I can’t recall the exact nature, something to do with boys and virginity. I remember so well the manufactured flick of her hand, designed to convey nonchalance. Yet that night, I found her alone in the dark, sobbing into her duvet. That rumour fractured more than one friendship and temporarily divided an entire year group.

It was the idea of smaller moments like these that breathed life into the setting of the book. The idea that being stuck behind four walls amplifies feelings in what is an already emotionally febrile environment. And of course, once the girls in my novel left the school, they also carried those feelings and experiences with them. They shaped them also. Just as they shaped me.

Rebecca Thornton is a journalist and runs an online advertising business. Her work has been published in Prospect Magazine, the Daily Mail, the Jewish News and the Sunday People. She was Acting Editor of an arts and culture magazine based in Jordan, and has reported from Kosovo, London and the Middle East. She is an alumna of the Faber Academy writing-a-novel course, where she was tutored by Esther Freud and Tim Lott. The Exclusives is published by Twenty7 Books. Read more.

Rebecca Thornton is a journalist and runs an online advertising business. Her work has been published in Prospect Magazine, the Daily Mail, the Jewish News and the Sunday People. She was Acting Editor of an arts and culture magazine based in Jordan, and has reported from Kosovo, London and the Middle East. She is an alumna of the Faber Academy writing-a-novel course, where she was tutored by Esther Freud and Tim Lott. The Exclusives is published by Twenty7 Books. Read more.

@rebs_web