It is us they burn

by Gila LustigerIn the course of the 2005 youth riots that broke out across France, thirty-two libraries were burnt down or so badly ravaged that their contents had to be thrown away. If one looks at the period covering 1996 to 2013 the tally rises to more than seventy. Libraries come under attack in the banlieues again and again. An attack can vary from broken windows and graffitied walls, via broken or looted furnishings and riots in the reading rooms to intimidation of the library staff. At the time the situation in the banlieues was giving rise to other, more pressing causes for concern, and not much attention was paid to this phenomenon.

Why did a place that not even ten per cent of the local residents used attract the wrath of the rioters to such an extent? What led them to desecrate and destroy this source of culture which was made available for free? Libraries are set up by the organs of state to raise social standards. So what do you do then when the very people for whom they were set up not only reject them, but actually destroy them?

The sociologist Denis Merklen stands alone in his search for an answer to this issue. In a case study published in 2014 and entitled simply Why do they burn libraries? he attempts to get to the bottom of what exactly it was that the rioters were attacking when they demolished yet another library. Between 2006 and 2011 Merklen interviewed many of those who had participated in those dramatic events in the département Seine-Saint-Denis, known colloquially as ‘neuf-trois’ from its postcode reference 93, and home to several of the social flashpoints such as Clichy-sous-Bois, which took place, like all the other signs of youth radicalisation, on the outer reaches of public awareness.

Merklen’s conclusions make clear that the educational model motivating the builders of the libraries utterly failed to relate to the young of the département for whom all this unstinting largesse was being spent. In Clamart they even furnished the library with designer furniture from Alvar Aalto, Arne Jacobsen and Harry Bertoia, which is now worth a fortune at auction. Whilst for some, libraries represent one of the cornerstones of a democratic society, guarantors of knowledge and culture, forgers of enlightened opinion and ambition, for others they constitute nothing less than yet further humiliation. Many of the rioters were school dropouts and their hatred was directed not just towards books but towards the written word in general which they saw as an instrument of their subjugation. Far from offering a way out of their milieu for these young people, the realms of language and the written word stood for only one thing: bureaucracy. Language skills were essentially for filling out the official forms they needed at the job centre or benefits office to get a medical slip or a certificate to obtain their dole money. Language meant laws telling them what they could and couldn’t do. Just another way of fencing them in. Teachers, social workers and police laid down the law from outside; from inside, it was language which kept them down: “They build us libraries to anaesthetise us. So we sit reading nice and quietly in our corner. We want jobs, and their answer is ‘Get an education and keep quiet’,” one of Merklen’s interviewees said.

Because they didn’t shout fire-and-brimstone invective, we forgot that the rage which leads a person to burn down a library contains the germ of the same idea: the rioters too were dividing the world into Us and Them.”

If that young man had left his comfort zone and done something really daring, set off on a journey into the unknown – had he, in other words, opened a book – he would have seen that somebody before him had made precisely the same demands of the lords and masters who are all too keen to teach you how to “live in obedience and avoid sin and misdeeds”. As Brecht’s Macheath in The Threepenny Opera sings: “You may proclaim, good sirs, your fine philosophy/But till you feed us, right and wrong can wait. Or is it only those who have the money/Can enter in the land of milk and honey?”

***

How come hardly anyone really noticed that libraries were being destroyed and librarians attacked? How come it didn’t bother any of us? That images of burning books didn’t frighten us? That not even I was reminded of 10 May 1933 in Berlin? That those sadly all too familiar images did not superimpose themselves in my mind’s eye on to the images of libraries burning in the suburbs? Why weren’t all my alarm bells ringing? Why didn’t I remember Joseph Roth’s prophetic words to his friends before the takeover of power in Berlin in 1932: “They will burn our books, but in their hearts it is us they burn.”

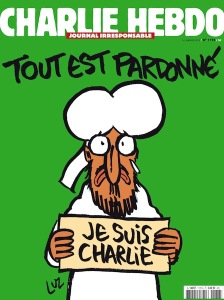

Seventy libraries in flames, and not one of us gave much consideration to the consequences of this encroaching phenomenon. It occurred to no one to recognise in these attacks symptoms of a disease whose natural course was to culminate in the assault on Charlie Hebdo and the terrorist attacks of 13 November 2015. Why did nobody point out that when they start burning books, soon they turn on the authors? The only possible answer is that none of us took the rioters from the banlieues seriously until the day when a dope-smoking pizza delivery boy and his brother stormed into the editorial offices of a magazine in order to kill twelve people. With the same blinkered condescension that the German chattering classes deigned to notice the noisy Brownshirts rabble back in the day, we paid brief attention to these losers, benefit scroungers and school dropouts who were down in the suburbs torching the cultural heritage we had so graciously made available to them that they might usefully better themselves.

We were dismayed, maybe somewhat disappointed, shocked, confused because they were destroying our culture. But were we frightened of these Philistines? Not in the least.

We were dismayed, maybe somewhat disappointed, shocked, confused because they were destroying our culture. But were we frightened of these Philistines? Not in the least.

People have been burning books ever since there have been books to burn. Those doing the burning had different motives. They burnt books they judged to be heretical or obscene, blasphemous or inflammatory, decadent or hurtful, but despite their differences of doctrine they all fell back on the same explanation: they divided the world into friend and foe, Us and Them, more and less valuable, into good and bad. The library arsonists in the banlieues acted with no ideological framework. And for precisely that reason: just because they didn’t shout fire-and-brimstone invective when they threw the books, we forgot that the rage which leads a person to burn down a library contains the germ of the same idea: the rioters too were dividing the world into Us and Them.

We assumed that with the libraries they were destroying symbols of the state, and many of us tried to justify this cultural vandalism by looking at social dysfunction and the frustration it engendered. But we forgot that anyone who is so suspicious of culture that they destroy it (all fascists incidentally), will sooner or later lose the capacity to think critically – the very capacity which makes discussing differences of opinion tolerable, even desirable. For culture and literature invite one to see the world through the eyes of someone else. And a library is always going to be one of those spaces which allow ideas, religions, worlds, sensibilities, experiences and opinions to co-exist and flourish.

It is all too easy to equate a book with its author, or confuse an author with his work, as the words of one of the Kouachi brothers show so clearly. The scene was filmed on a smartphone by a witness who had managed to escape onto a roof and it was doing the rounds on the internet the next day. As the brothers were running back to their black Citroën C3 one of them cried out: “We have avenged the prophet! We have killed Charlie Hebdo!” He could have named the cartoonists, or called out their noms de plume, because in the final analysis, they hadn’t shot Charlie, but Charb, Cabu, Tignous and others, but for that they would have had to have seen their victims as individuals. They had been indoctrinated by an ideology which dehumanised and demonised others.

What can you possibly say to someone who claims he would rather obey God than Man and thus

is convinced that he will go to heaven if he cuts your throat? More often than not the fanatics are

guided by villains, who press the dagger into their hands. – Voltaire, Treatise on Tolerance.

After the Charlie Hebdo attack this plea for tolerance, which first appeared in 1703, reached the bestseller list, because many French people affirmed their values through the medium of culture. It’s a paperback and costs 2 euros. Needless to say, this brief text, in which Voltaire sets out the need for tolerance, would have been on loan from any one of the destroyed libraries.

We must all bear with one another, because we are all weak and faltering, we are all subject to

change and error. Does a reed bent down in the mud by the wind say to another reed bent in the

other direction: Bend the same way as me or I will complain and get you pulled up or burnt?

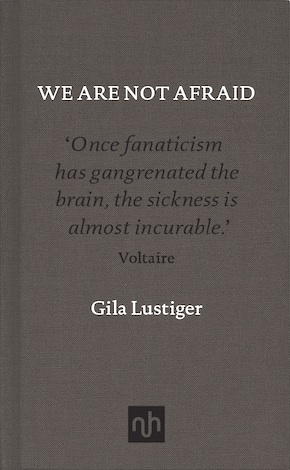

This is an edited extract from We Are Not Afraid, translated by Jane Purrier

Gila Lustiger was born in Frankfurt in 1963. She studied German and Comparative Literature in Jerusalem before settling in Paris in 1987, where she continues to live and work. She is the author of six published novels and was shortlisted for the German Book prize in 2005. Her most recent novel, Die Schuld der Anderen (The Guilt of Others), won the Jakob Wasserman Prize. We Are Not Afraid (originally published in German under the title Erschütterung − Über den Terror) was awarded the Horst Bingel Prize 2016 and the Stefan Andres Prize 2017, and is out now from Notting Hill Editions.

Gila Lustiger was born in Frankfurt in 1963. She studied German and Comparative Literature in Jerusalem before settling in Paris in 1987, where she continues to live and work. She is the author of six published novels and was shortlisted for the German Book prize in 2005. Her most recent novel, Die Schuld der Anderen (The Guilt of Others), won the Jakob Wasserman Prize. We Are Not Afraid (originally published in German under the title Erschütterung − Über den Terror) was awarded the Horst Bingel Prize 2016 and the Stefan Andres Prize 2017, and is out now from Notting Hill Editions.

Read more

Author portrait © Lilian Birnbaum

Jane Purrier graduated in modern and medieval languages from Cambridge and subsequently became an interpreter in Brussels and eastern Europe, before raising six children as diplomatic wife to an EU ambassador. She now lives with an overworked French doctor in Provence, where she spends her time reading, riding, cooking and finding rewarding displacement activities to avoid writing The Novel.