A butterfly in January

by Joanna Cannon

“A gripping debut about the secrets behind every door.” Rachel Joyce

Tilly and I stood on the corner together, kicking our feet and sending sprays of white into the air.

“Has your dad gone to work?” she said.

“No.” I did an especially big kick. “He’s gone to get provisions.”

Tilly stopped kicking. “What are provisions?”

“It’s what people call food when it snows,” I said. “Fancy not knowing that.”

Tilly shrugged her whole duffel coat.

“I’m bored with this already.” I kicked again.

“It’s a day off school,” said Tilly. “Aren’t you pleased, Gracie?”

“Oh yes,” I said, “very much. But what’s the point in a day off school when there’s nothing interesting to do?”

Tilly pushed her hands further into her pockets. “At least we have each other. I was worried I wouldn’t be able to find you. Nothing looks the same. Everything’s disappeared.”

“I know. But just because we can’t see something, doesn’t mean it’s not there. Look.”

I walked across what used to be chippings and grass, towards the two empty garages in the far corner. They didn’t have doors anymore, and the weather had swept itself inside, turning them into wintery shells. I pointed to a bank of snow.

“This, for example.” I pointed it to it with the tip of my wellington. “Is that old rubber tyre.”

“Is it?” said Tilly.

I brushed the snow away with the edge of my sleeve.

“Oh, so it is,” she said. “I wonder where everything else is.”

She spun around. Tilly wasn’t the best spinner on an ordinary day. When she’d heaved herself back up, she pointed to another mound of snow next to the fence. “What’s that, then?” she said.

I couldn’t work it out at first, and then it came to me.

“It’s that old plastic chair Mr Lamb uses, when he fishes leaves out of the drainpipe,” I said.

Tilly turned back to the garages. “Then where’s the drainpipe?”

We both stared at the wall.

“It’s there somewhere,” I said.

We fell back into the snow. It felt like a pile of cushions. The air filled with clouds of breathing and laughter, and it was only when I lifted myself up onto my elbows that I spotted it.”

We put on our gloves, and brushed at the drift with our coat sleeves, but no matter how much we brushed, and how deep our coat sleeves went, we couldn’t find the pipe. It seemed to have vanished from where it was supposed to be.

“Shall we give up?” said Tilly.

(Tilly gave up far too easily, in my opinion.)

I dug harder into the snow and Tilly joined in, and it powdered our hair and our faces and stole away our breath. I was just thinking Tilly might be right after all (although it doesn’t do to admit that too often) when the button on my coat sleeve hit against metal.

“It’s here,” I said, and the drift broke away and the drainpipe appeared, dirty and chipped, and covered in old paint.

We fell back into the snow. It felt like a pile of cushions. The air filled with clouds of breathing and laughter, and it was only when I lifted myself up onto my elbows that I spotted it, pushing its way out of the snow near the drainpipe. Afterwards, Tilly said she was surprised we saw it at all, but it was impossible to miss – scarlets and emeralds and turquoise, dancing and twisting around our heads.

“It’s a butterfly!” said Tilly.

“It’s a butterfly!” said Tilly.

“In January?” The butterfly rested on a brush of white, and we stared at it. “You don’t get butterflies in January.”

“You get this one.” Tilly held out her hand and it landed on the edge of her finger. “No one will believe us.”

I studied the butterfly. It was fragile, almost translucent, and it trembled on Tilly’s hand, as if it were worried we might think it had just been imagined. But its colours were vivid and certain, and bright. The whole of summer had been painted upon its wings.

“Perhaps we could catch it. They’d believe us then,” I said.

The butterfly seemed to hear, because it flew from Tilly’s finger and danced in the space above our heads.

We stood, and it danced a little further away.

“I think it wants us to follow,” said Tilly.

“I think you’ve been watching too much Jackanory,” I said.

But we started walking anyway, arm in arm, holding each other up in the snow.

The butterfly beat its wings and waited.

“I wonder where it’s taking us?” said Tilly.

And I decided the day was going to be far more interesting than I had originally thought.

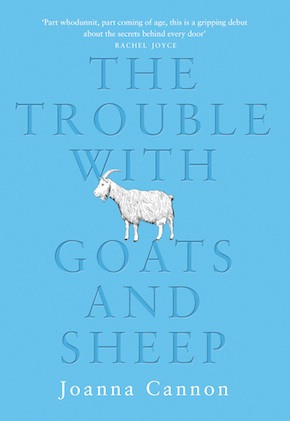

This is the second part of ‘The Greatest of These’, a standalone story featuring junior detectives Grace and Tilly from Joanna Cannon’s debut novel The Trouble with Goats and Sheep, published by The Borough Press in hardback and eBook. Read more.

This is the second part of ‘The Greatest of These’, a standalone story featuring junior detectives Grace and Tilly from Joanna Cannon’s debut novel The Trouble with Goats and Sheep, published by The Borough Press in hardback and eBook. Read more.

joannacannon.com

@JoannaCannon

#GoatsandSheep

Read part one at Litro

Part three: For Winter Nights

Part four: The Writes of Woman

Part five: Popshot magazine

Part six: The Debrief

Part seven: London Review Bookshop blog

Author portrait © Philippa Gedge