Cat

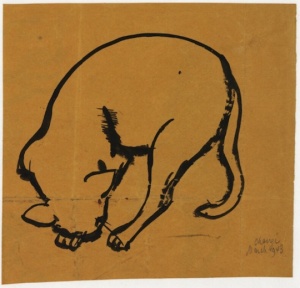

by Fleur JaeggyObserving others is always interesting. On a train, in airports, at conferences, while waiting in line, when sitting across from someone at a table; on any occasion, in fact, that people flow into. Even someone who doesn’t travel or is very much alone will at some point go out on the street for half an hour. And observe a cat terribly concentrated and alert, stalking his prey. Or clawing it. Maybe it’s a butterfly, or a leaf, or a piece of paper, an insect. On reaching the target, suddenly a cat becomes distracted. Animal behaviourists call this movement Übersprung. It happens just before the deadly blow. We see the cat shift and move the prey as if it were a feather. The last moves. The butterfly dances its agony. It vibrates imperceptibly, and this attracts further interest from the cat. And then he looks away. Walks away. Calmly, he changes route. Changes the mental route. It is like a dead moment. Stasis. It’s as if nothing interests him. It’s as though he has forgotten the fluttering wings that only moments earlier had inspired his total dedication. That which had possessed him before, as though it were an idea, a thought. Now he pulls away. Looks elsewhere. With his little paw he rubs his muzzle. With his little paw he scratches behind one ear, head bent. He has many tasks to fulfil. They have nothing in common with the preceding one. With action. The cat is looking elsewhere. He is elsewhere. It is a strategic move. It is part of a mechanism of precision. All of it is reminiscent of the puppets in Kleist’s story. The precision of the assault, the lightness and agility. The detachment, the distance. Maybe the butterfly and the leaf have the same moment of Übersprung. Like the cat. They distract themselves from agony, abstract themselves from their own death. From the idea of death. That’s what the cat does. He distances even himself from the agony. That he has inflicted. We don’t know why it is that the cat turns his gaze away. He knows why. Who knows, maybe this Übersprung is a delectatio morosa. A melancholic doing away with any connection to the victim. Übersprung: a word that involves us, too. It is a turning away, going on to something else, manifesting a gesture of detachment, like a goodbye. Wandering from the theme, escaping from a word – at once hunting for words and doing away with them: these are all a mind’s modes of writing. Some write according to delectatio morosa. Thomas de Quincey, for instance, once hinted at the ‘dark frenzy of horror’.

From the collection I Am the Brother of XX, translated by Gini Alhadeff

From the collection I Am the Brother of XX, translated by Gini Alhadeff

Fleur Jaeggy was born in Zurich and lives in Milan. Her previous books include S.S. Proleterka and Sweet Days of Discipline. She has translated the works of Marcel Schwob and Thomas de Quincey into Italian and written texts on them and on Keats. I Am the Brother of XX, translated by Gini Alhadeff, is published by New Directions in the US and And Other Stories in the UK.

Read more