A clandestine Christmas

by Agi Jambor

“Agi Jambor’s memoir has a rare quality of humanity; an unyielding power as a testimony and as a final tribute, as a gesture of mourning and of closure in the aftermath of an unhealable wound.” Mika Provata-Carlone

One day I went with the general 1 to the Swedish Legation to get some protective passports for his daughters. I met there a young man – one of the most handsome young men I have ever seen – in the garb of a Catholic priest. I looked at him,then looked again, and sure enough, I recognized him. He was a young conductor whom Imre 2 and I had helped in his musical education. He had practically become a member of our family. Obviously, he was impersonating a priest. I greeted him properly, “Jesus Christ be praised,” which is the correct way to salute a priest in Hungary. The correct answer is, “Forever and ever, Amen,” but the young rascal answered, “Hello.” I said to him very softly, “You donkey, what happened to you?” “I became a Catholic priest, as you see,” he answered, then we withdrew to a corner where he told me his story.

Some time before, he was being driven on the street, together with a large group of other people, to deportation in a German concentration camp. A Catholic priest saw him, he walked up to him and said, “Come with me.” The young man answered, “I can’t, they will kill me.” However, they soon came to a bend in the road, and he was able to step out of the group. The priest took him to a monastery, gave him a cassock, and provided him with the papers of a deceased priest. Steve then went to one of his former professors and asked his help. The professor told him that the priest of his church had recently died in a bombing attack, and the community needed a priest. Steve learned very quickly how to baptize, how to bury and perform marriages, and he made a very satisfactory priest. Perhaps I might as well tell the rest of his story here. Steve stayed with his flock for the next three months, until the Germans left. In those confused times nobody realized the deception. His congregation loved him, and they tried to persuade him to stay after the war was over. But he left and became assistant conductor of the Opera in Budapest. He is now professor of music at one of the leading universities of Canada.

The general noticed my long conversation with Steve at the Swedish Legation. He asked me who the young priest was and I told him his story. Just as I finished, a nun entered the legation. The general looked at her, then winked at me and said, “I guess you will tell me next that that nun is your mother.”

One morning at the usual time, 5:30, the doorbell rang in Mr Posfay’s 3 apartment. We felt sure that at this hour the visitors would come only from the Gestapo or the Arrow Cross 4. Our bathroom-bedroom was the nearest to the door, so we were supposed to open it. Imre had in the room about ten papers that he had recently ‘washed’ and dried, and it wouldhave been pretty sad if they had found them on us. In addition, Mr Posfay had a gun in his room, which was against the law, and he also had a number of important documents hidden in his bedroom. He had taken these from the Foreign Ministry when the Germans occupied Hungary; he wanted to preserve them from destruction by the Nazis.

I wanted to keep the conversation going as long as possible. I talked loud and used as vulgar language as I could imagine… I think I played my role of a former prostitute most satisfactorily.”

Imre immediately began to destroy his papers by flushing them down the toilet as fast as he could. The bell began to ring again, more insistently, so I told Imre I had better go to open the door, otherwise they might break it down and throw in a few hand grenades. When I opened the door three rifles were directed at me, held by three Arrow Crossists. One of them inquired: “Where is Virgil Posfay?” I answered: “Do you think that I would know where an important man like his Excellency is, or what he is doing?” The leader of the three asked me then who I was. I replied: “I am Mrs Kocsmaros. I ran away from the Russians with my man, and this goodhearted gentleman accepted us in his house as refugees.” The Nazi then inquired: “Is it true that a Russian is hidden in this house?” I answered very emphatically: “No, it is not true.”

Agi Jambor just before the war, courtesy agijambor.org

I wanted to keep the conversation going as long as possible to give Imre and Mr Posfay time to hide the incriminating evidence. I talked loud and used as vulgar language as I could imagine… I think I played my role of a former prostitute most satisfactorily. I told them how the Russian soldiers had raped us women, and bawled them out unmercifully for using their guns against us peaceful citizens instead of fighting the Russians. I even threatened them that I would go back to the Russians. They doubtless felt that this would be a calamitous blow to the Nazi cause, for they listened to me with open mouths, unable to put in a word edgewise.

Finally Mr Posfay appeared on the scene to rescue the Arrow Crossists. In his usual kindly tone he asked: “What do you wish, gentlemen?” The leader of the group said: “My name is Brother Megadja.” The Arrow Crossists called each other ‘brother’, just as the Communists call each other ‘comrade’. (Incidentally, Brother Megadja was one of the first Nazis hanged after the war, for mass murder.)

I interrupted: “Can I go back to my man now?” Brother Megadja slapped me on the back and said: “Go on back, lass.” I departed, and the three Nazis followed Mr Posfay into the apartment. They searched the rooms pretty thoroughly but of course, they found nothing. Disappointed, they ordered Mr Posfay to go along with them for a hearing. The old diplomat answered: “My good friends, I cannot go with you. I must have my shave and bath first. I shall appear at your headquarters at 8 o’clock sharp.” It must have been the first time that the ‘brothers’ had met anyone so calm and collected, so they answered: “All right, we will expect you at 8 o’clock.”

After they left, Mr Posfay called all of us into his living room. We held a little conference there and decided that in case he did not come back from the hearing in about two hours, we would all disappear from the house. However, to our joy, he came back in less than an hour, telling us that his visit at the Nazi headquarters turned out to be a complete flop. When he got there, he found the three ‘brothers’, together with three girls, in the midst of a drunken orgy, and nobody seemed to be in the least interested in him. Unfortunately, it was not at all certain that the whole story would end there, so he advised us to scatter for two or three days, and promised that he would keep us posted about what was happening.

I stopped to buy some bread. When I opened my purse I realized that I had forgotten to bring my identification papers along. This meant great danger because the Arrow Cross was holding constant raids all over the city.”

Imre and I decided that we would become Swedish citizens again for a while, and went to a ‘Swedish’ house where a considerable part of our family lived. At that time there were two ghettos in Budapest. Most of the Jews and yellow star people of Budapest were crowded into a ghetto in the center of Pest; this place was surrounded by walls and closely guarded. The other was the international ghetto, where those victims of the Nazis lived who were protected to some extent by one of the foreign legations. This ghetto had no walls but each house was guarded by its janitor armed with a gun, and no one could enter or leave without permission.

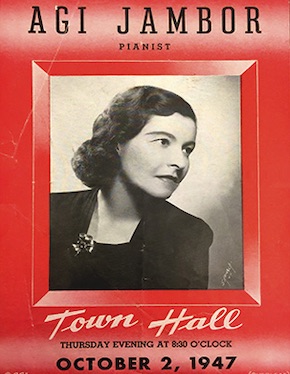

An early concert in America, courtesy agijambor.org

The Swedish house into which we moved had previously been a peaceful apartment house where among others, some of the pure ‘Aryan’ part of our family had lived. When the house was designated a Swedish house, i.e., a house for yellow star people who were under Swedish protection, they decided to stay on (Aryans who wanted to stay in their own homes did nothave to move out). Later, some of the non-Aryan part of our family obtained Swedish protection, and they also moved into this house. When Imre and I moved in temporarily, we shared a room with about eight people. The two of us slept in the same bed with the brother and sister-in-law of Peter Lorre, the American movie star. In this two-room apartment on the fifth floor of the house some twenty people tried to live. It was not an easy life. About the only food we had were peas and beans, supplied by the Swedish Legation.

Imre’s brother and his wife lived in the same house on the second floor. He was a wonderful mathematician and violinist and, like Imre, he had a very fine spirit. They had with them his ninety-year-old paralyzed mother-in-law and his blind sister-in-law. He visited them every day. All the candles were gone now, so we sat in the evenings in complete darkness. By sitting I mean that my brother-in-law had on one knee his wife and me on the other, and Imre sat somewhere on the arm of the chair. Still, it was not an entirely joyless life, for Imre and his brother held the most inspiring conversations that I have ever heard in my life during these black evenings of ‘involuntary laziness’.

On the third day that we were in the house, the 24th of December, 1944, Imre said that we ought to find out what Mr Posfay was doing. It was Christmas time, and we felt that we should remember him for his inexhaustible kindness with some sort of a gift. We had absolutely nothing, but my brother-in-law gave us two books to give him as a present. I decided to take it to him immediately. I took on the identity of Mrs Kocsmaros and started on the journey. When I reached the streetcar station they told me that there were no more cars going across the bridge to Buda. I was determined to perform my errand anyhow, so I walked.

In the house next to Mr Posfay’s there was a baker, and I stopped at his store to buy some bread. When I opened my purse to pay him I realized that I had forgotten to bring my identification papers along. This meant great danger because the Arrow Cross was holding constant raids all over the city. People were being examined on almost every street corner. What worried me even more was that Imre would find out that I had left without my papers and would become terribly upset.

I arrived breathlessly at Mr Posfay’s door, and told him: “I do not know what to do, I forgot to bring my papers.” Fortunately Juliska, the cook, immediately came to my rescue and said: “Don’t mind it, Mariska, you can go home with my papers and bring them back tomorrow.” There was nothing to do but to accept, so I quickly found out from Juliska her entire family history, changed myself from a laundress to a cook, and started back. I arrived home safely. As I expected, Imre had discovered my papers and was worried to death.

The next day was Christmas. The Aryan part of our family succeeded in getting some poppy seeds and sugar, and made the favorite Hungarian dish, noodles with poppy seeds. We sat around in a family circle, almost like in old times, when suddenly a terrific explosion jerked us to our feet. The siege of Budapest had begun.

1 The General, a member of the underground movement, was ‘Aryan’ but his daughters were Jews, since his wife, although a devout Catholic, belonged to the Jewish race.

2 Agi Jambor’s first husband, the scientist Imre Patai.

3 Virgil Posfay, Hungary’s Ambassador to Switzerland in peacetime, who held various other distinguished posts in the Foreign Service.

4 A far-right Hungarian nationalist party led by Ferenc Szálasi, which governed from 15 October 1944 to 28 March 1945.

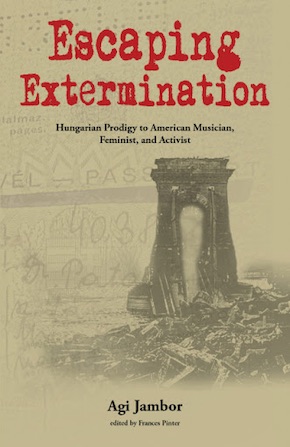

From Escaping Extermination (Purdue University Press)

Agi in the 1950s, courtesy agijambor.org

Agi Jambor was born in 1909 in Budapest, Hungary, the Jewish daughter of a wealthy businessman and a prominent piano teacher. A piano prodigy, she was playing Mozart before she could read and at the age of twelve made her debut with a symphony orchestra. She studied under Zoltán Kodály and was a pupil of Edwin Fischer at the Berlin University of the Arts. Arriving in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1947, she was widowed shortly thereafter. She became a professor of classical piano at Bryn Mawr College and was briefly married to the actor Claude Rains from 1959 to 1960. Agi’s life in America was full of intellectual and musical abundance. She was active in opposing McCarthyism and fought against the Vietnam War, giving proceeds from concerts to her charity that bought food for Vietnamese children. She was much loved by students as a charming yet feisty role model. She died in 1997 in Baltimore. Her wartime memoir Escaping Extermination, edited by Frances Pinter, is published by Purdue University Press.

Read more

agijambor.org

Buy from bookshop.org

Frances Pinter, born of Hungarian parents in Venezuela, grew up in the United States. Only in her early teenage years did she meet her relative Agi, who became her role model. Frances made a career in academic publishing in London. In the 1990s she worked for the Open Society Institute, supporting independent publishing all across the post-communist region. In February 2020, she took on the newly created role of executive chair of the Central European University Press in Budapest.

pinter.org.uk

@francespinter

Monday 16 November

A Virtual Book Talk: Escaping Extermination

The Wiener Holocaust Library

7 to 8pm

Free

The Wiener Holocaust Library welcomes Julia Neuberger, Rachel Polonsky, Mika Provata-Carlone and Robert Max in conversation on how music and art sustain the human and much more, to mark the publication of Agi Jambor’s extraordinary memoir.

Replay on YouTube

@wienerlibrary