Crossing bridges

by Kalyan RayWhen I first migrated to New York, a wide-eyed student with a frugal scholarship, I felt no fear, for Manhattan was connected to other land-masses by half a dozen bridges. That calmed an inner part of my soul. Given my family history, I do not know how it could be otherwise.

Until that point, rivers seeped into every cranny of my family lore. By the mid-1940s, my family had moved to a palatial house being built beside a wide river which my grandfather’s bridge would span. An engineer who had written important books on the great alluvial rivers of East Bengal, he was in charge of designing and building this one, his crowning achievement. He prodigally spent almost all of his considerable personal funds building the house on whose spacious verandah he planned to sit upon retirement – which was not far – and contemplate the bridge. His Taj Mahal. The bridge was near completion, just one crucial part waiting to be put in place, a technically delicate final step. Except it did not quite happen that way.

At this critical stage, my grandfather was informed that he was being replaced by a callow young English officer with little technical training; his double-barrelled Anglo-Saxon name was to adorn the plaque on the pediment of the bridge.

My grandfather resigned in high dudgeon and took with him the technical plans he had designed. This was interpreted by the authorities as typical oriental duplicity only to be expected from the devious wog. That last crack must have struck home, for my grandfather forthwith burnt his beloved bespoke silk ties and double-breasted suits, fancy waistcoats and cravats, and took to wearing nothing but immaculate home-spun khadi garments which Gandhi, years ago, had urged upon all patriots. He sat for countless hours on his own incomplete verandah, staring at the incomplete bridge. My grandmother complained that he had begun to grind his teeth in his fitful sleep.

The precipitous events leading up to Partition overtook him in his reverie, catching him completely unprepared. The house was on the wrong side of the river on a map of India which an Englishman sitting in a great English university used, slicing away the eastern wing to make up a whole new country. Violence and confusion grew out of each other and swept through the land, first rumours, then riots and abrupt killings. Hindus and Muslims began to cross pell-mell to either side of the new border. My stranded family blamed fate, British imperial policies, colonialism, His Majesty George VI whom they no longer considered handsome, and finally – inevitably and vituperatively – my grandfather.

The precipitous events leading up to Partition overtook him in his reverie, catching him completely unprepared. The house was on the wrong side of the river on a map of India which an Englishman sitting in a great English university used, slicing away the eastern wing to make up a whole new country. Violence and confusion grew out of each other and swept through the land, first rumours, then riots and abrupt killings. Hindus and Muslims began to cross pell-mell to either side of the new border. My stranded family blamed fate, British imperial policies, colonialism, His Majesty George VI whom they no longer considered handsome, and finally – inevitably and vituperatively – my grandfather.

News arrived that there would be a night attack. People apparently believed ridiculous whispers that my grandfather had hidden gold in the walls of his new riverside mansion. They were going to simply burn the house down to get at it. The gold would be purer by the inventive mode of their getting at it. All things considered – went the loud murmurs in the family – it would be prudent for us to cross over, as quickly as possible. That would have been a simple matter had the bridge been completed, but the wide monsoon-vexed river lay between the family and safety.

That night my grandfather with his sons lashed together what timber could be salvaged. As quietly as they could, they urged my grandmother, my idiot aunt, and my very pregnant mother on to what they called a raft. The ebb-tide swirled around their ankles.”

Ah – but mine was the old-fashioned Indian family replete with grown offspring, some of whom had children of their own, various relatives who had attached themselves like barnacles over the years – a stubborn variety of unemployed cousins – prehistoric great-aunts and other relicts, retainers ancient and young. It was simply called the ‘joint-family’, a large and compliant bitch with many teats. There were inbuilt and intricate tiers of importance and neglect. But there they were now, milling around distractedly, gathering and misplacing bundles of clothes, utterly at a loss. But in the midst of their chaos, they were unanimous in their condemnation of my grandfather whose ‘salt’, as the saying goes, they had eaten for years.

They all decamped in the darkness, leaving my grandfather and his immediate family behind. Out of that night rose a tremendous wind and rain, and the rumoured attack never happened. My grandfather had sat on a chair next to a kerosene lamp at the head of the main staircase, cradling his ancient hunting rifle, red-eyed with lack of sleep. The house was quiet without all the other relatives.

In the clear light of the next dawn, he went to the verandah from where he could see that the returning tide had tugged back their floating bodies, charred remains of dinghies, their soggy bundles among torn branches and debris in the swirling rush of the monsoon-gorged river.

That night my grandfather with his sons lashed together what timber could be salvaged. As quietly as they could, they urged my grandmother, my idiot aunt, and my very pregnant mother on to what they called a raft. The ebb-tide swirled around their ankles. My grandfather, who had studied the river for the last decade, cast off at a carefully calculated moment, and they floated, guided by his single salvaged oar. There was only one mishap when a beam of the bridge seemed to rise up out of the dark water to glance off the side of the raft. No one was hurt, except my mother who fell on her side and fainted briefly. The rest of the trip was uneventful, if tense, and they reached the other muddy shore, a new nation under a sickly morning moon.

My mother lost the baby, but becoming pregnant some months later insisted it was the same baby come back. No one ever contradicted her. And I was born in a brand new country, growing up with the lore of bridges, built and unbuilt.

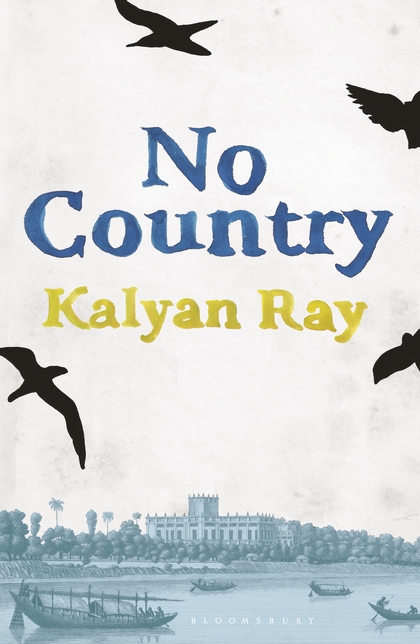

Kalyan Ray’s family was uprooted from the Ganges Delta (now Bangladesh) through a combination of natural disasters, political upheaval and poverty. He grew up in Calcutta, was educated in India and the US, and now lives in both countries. He is the author of the novel Eastwords (published by Penguin India) and several books of translations of contemporary Indian poetry. His latest novel, No Country, a rich tale of exile and identity and a murder two centuries in the making, is published by Bloomsbury in hardback. Read more.

Kalyan Ray’s family was uprooted from the Ganges Delta (now Bangladesh) through a combination of natural disasters, political upheaval and poverty. He grew up in Calcutta, was educated in India and the US, and now lives in both countries. He is the author of the novel Eastwords (published by Penguin India) and several books of translations of contemporary Indian poetry. His latest novel, No Country, a rich tale of exile and identity and a murder two centuries in the making, is published by Bloomsbury in hardback. Read more.

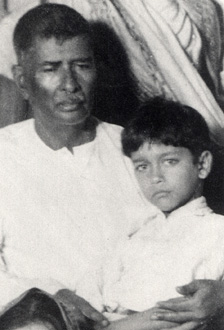

Author portrait © Ethan Shapiro; Young Kalyan Ray with his grandfather (above) courtesy of the author