Dangerous for ordinary people

by Mika Provata-CarloneIt takes great determination and mettle to give voice to silence; to look at closely, and truly see what has become invisible or been reduced to transparency. Louisa Treger evinces both purpose and mettle, deep knowledge and fine understanding in The Lodger, her debut novel about the writer Dorothy Richardson, someone who is often overlooked by readers and critics alike. Richardson was too quiet for some, too explosively subversive for others. She is often seen as the unspoken modernist, the blurred, obscured and neglected mirror image of Virginia Woolf, Charlotte Perkins Gilman and Katherine Mansfield, perhaps as the female echo of James Joyce, Marcel Proust, Henry James or D.H. Lawrence, of Gorky, Hermann Broch or Dostoyevsky. For H.G. Wells, the other prominent figure in Treger’s novel, she was infuriatingly male and female, a strong, brilliant mind in a highly desirable soft body: “she wanted some complex intellectual relationship, [s]he wanted me to explore her soul with wonder and delight. But a vein of evasive ego-centred mysticism in her has always made her mentally irritating to me; she seemed to promise the jolliest intimate friendship; she had an adorable dimple in her smile; she was most interestingly hairy on her body, with fine golden hairs, and then – she would begin intoning the dull clever things that filled that shapely, rather large, flaxen head of hers; she would lecture me on philology and the lingering vestiges of my Cockney accent, while there was not a stitch between us.” (H.G. Wells, H.G. Wells in Love, p. 64). As he says in Treger’s novel, “a fellow would always rather be listened to than talked at.”

Yet Richardson is and should be considered as monumental in her way as that sacred monster Wells: she wrote one of the first, boldest, most ground-breaking stream-of-consciousness novels ever attempted, published in the same year as Virginia Woolf’s The Voyage Out and only a few years after Édouard Dujardin’s pioneering Les Lauriers sont coupés. Her novel Pilgrimage has been hailed as a foremost example of this new way of writing that strove to capture the moment of being, the very heartbeat of existence, and hers was a voice so tremendous and yet so stifled, so quiet and subdued and yet so full of thundering life, that only her own bubbling, unleashed voice as a writer could suffice as the observant voice of her own singular, constantly evolving and rarely observed life.

There are now substantial studies and biographies of Richardson. Yet what Treger has achieved is quite unique and should be considered also quite significant. She has managed to convey with acumen, narrative sharpness, lucidity but also kindness the enormous contradiction in Richardson’s character and also in Richardson’s writing, namely the struggle to create aesthetically, philosophically and spiritually, and at the same time simply subsist, lead a practical and if possible a happy personal existence. Treger captures Richardson’s ambivalence between female and male stereotypes, between puritanism, overmastering mysticism and voracious sensuality, and uses two ‘voices’ in her novel, one the voice that writes the time and days of her characters, and the other the inner voice of Richardson thinking, speaking, formulating her own images and tense visions. Tension is certainly a crucial term here, for in Richardson there brewed an inner storm of feeling and words, there was a flaring yearning for experience and real life. At the same time there are the suffocating restrictions of her existence: material, psychological, social, historical, feminine, perhaps, above all.

This is a book with a passionate love for the art and craft of storytelling, for the skill of listening to and rendering a living voice, and Treger is clearly attuned to Richardson’s own style, which she adapts to her creative purpose as well as emulates. It is a book with sharply absorbing observations about art and life, history and private being. It is certainly a woman’s book in the starkest, often most troubled sense, a daughter’s book, though not a mother’s. Above all, it is women’s story inside the storybook of men. We see women looking at themselves and at each other timidly, intimately, audaciously, ferociously, within the world of men who live and build that world as if it were their own exclusive magnum opus of fairy tales and heroic feats. Treger has Richardson say that H.G. Wells’ second wife ‘Jane’ “was a persona created by her[self] and [him], someone who was able to cope with the demands of their joint life. Amy Catherine [Jane’s real name] was more real, real and vulnerable. But she was all but buried beneath that construct that was Jane”, a comment that feels piercingly too close for comfort. “We will have all life within the novel” proclaims Wells two pages later, and the ramifications now become sinister: everyone in Wells’ life, we are told, becomes a character, renamed and redefined within his own masterfully monstrous novel of his life. In this context of repressed existence and explosive yearning, the leading motif throughout is the vital urge to escape without self-destructing, to control instability, the ‘basis/abyss’ conundrum of later modernist writers such as Spender.

Treger is particularly gifted at conveying an atmosphere, a landscape, the inside or the outside of a building, a rose garden; transfixing when she enlivens the public and private struggles it took to allow the political voice of women to be heard.”

The Lodger is a book of many books, of Richardson’s Pilgrimage, certainly, but also other books forming triangles, like the triangles in Richardson’s real life. There is a clear hint of Orlando, with a middleclass Bloomsbury boarding house standing for Knole House, women powerfully, even more subversively in love, Ulysses-like characters moving in smaller urban spaces, with less daring but as many echoes and as much humanity. Wells’ voice is there too, and unmistakably, the voice that tried to find the prescription and the formula for both passion and reason, for both grand history and the humble ambiguity of existence.

Treger fleshes out the period, its anxieties, visions, cravings, limitations. She is particularly gifted at conveying an atmosphere, a landscape, the inside or the outside of a building, a rose garden; transfixing when she enlivens a suffragette rally, Holloway Prison, the public and private struggles it took to allow the political voice of women to be heard. She is devastating when telling about death, miscarriage, tears – and often laughter. Treger mutes, and wisely, the evident parallels and accidental convergences in the real historical world: the other, real, looming triangles of Virginia Woolf, Leonard Woolf and Vita Sackville-West, or of Harold Nicolson, Vita again, and Rosamund Grosvenor or Violet Trefusis, these nobler, more solid and aristocratic, more free to dare, taste and proclaim alter egos to the more “ordinary and normal” Dorothy Richardson, H.G. Wells and Veronica Leslie Jones, who longed, lusted but also cringed and feared. We only have a fleeting, trenchant mention of Virginia Woolf when they both publish their first extraordinary novels. Richardson was Woolf’s equal and worthy of the challenge, Treger tells us, and hers too was an original female voice, one that will now be perhaps sought out and listened to.

In The Lodger Treger does not shy away from historical or private reality, from the reality of sexuality or the borderless limits of the erotic, yet she will not pry; her vision penetrates, explores, presents, but never indulgingly exposes. She is not afraid to show us in close detail these ordinary normal lives caught up in their dangerous attempts, and tackles the romantic, the mundane and the explicitly intimate with equal verve and with a scholarly mind. She explores the emotional, the physical, the intellectual, the public and the everyday world, and especially the effects of any one-sidedness on the novel’s clearly yearned-for wholeness. Throughout the novel she shows her skill as a perceptive, impartial and deeply sympathetic observer and chronicler of lives, and even in her portrayal of Wells, “that luminous mercurial man”, our sense is of human fallibility, of lamentable clay-feet in greatness.

At the same time there is always a sense of dire, impending risk, of incongruence between the actors and the acts, the task her heroes and heroines undertake. “The liaisons which you and I contract are something perfectly apart from the more natural and normal attitude we have towards each other. But it would be dangerous for ordinary people,” wrote Vita, Lady Nicolson, to her singularly complex and unordinary husband Harold. Treger takes us through her characters’ climactic states of suspense between the normal, the ordinary and the larger-than-life, to a cathartic vision: Richardson will transform both danger and ordinariness into unique writing and a lived, thoroughly intriguing existence.

There is an unmistakable, alluringly enigmatic quality in Treger’s writing, behind the wealth of detail, Richardson’s torrential adjectives, and imagined or researched moments of being. And it is this fleeting glimpse at the author which makes the novel particularly responsive and engaging. Like her heroine, she writes with “precision… and inexorable veracity”, and counters effectively Richardson’s comment to Wells that “Nothing real can be expressed in words.”

Richardson’s later life is no less full of vivid attraction: she continued to write, almost about everything, and married Alan Odle, an artist combining the acid daring of Beardsley and the crushing critical eye of Hogarth. Then, in the 1930s, she actively supported refugee writers fleeing from Germany, and it would be riveting to imagine a dialogue between her and the magnificently tragic Ernst Toller in this context. Treger does not tell us about that future, she only foreshadows and suggests it, so we finish The Lodger with both satisfaction and yearning: the satisfaction that this was “a struggle [well] worth setting down on paper”, and a struggle about which one can only yearn to find out more.

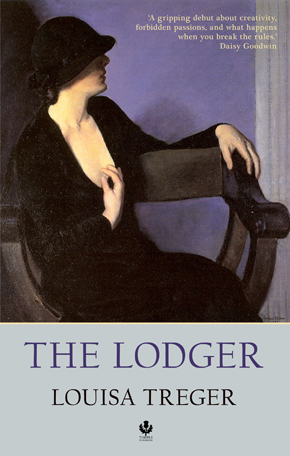

Louisa Treger studied at the Royal College of Music and the Guildhall School of Music, and worked as a freelance orchestral player and teacher. She subsequently gained a First Class degree and a PhD in English at University College London, where she focused on early twentieth century women’s writing. Married with three children, she lives in London. The Lodger is published by Thistle Press and Thomas Dunne Books/St Martin’s Press. Read more.

Louisa Treger studied at the Royal College of Music and the Guildhall School of Music, and worked as a freelance orchestral player and teacher. She subsequently gained a First Class degree and a PhD in English at University College London, where she focused on early twentieth century women’s writing. Married with three children, she lives in London. The Lodger is published by Thistle Press and Thomas Dunne Books/St Martin’s Press. Read more.

louisatreger.com

@louisatreger

Author portrait © Nicholas Harvey

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.