Disciplines of disobedience

by Ra Page

“During a time of political division and rise of the far right, this generation may need to learn from their history and be ready to rise up to the occasion.” Manchester Literature Festival

‘Let’s do this copper bastard over.’ These are the words my father was accused of saying before his arrest on the anti-Vietnam War protest of 30 March 1968 as it progressed towards Grosvenor Square, then site of the American Embassy. The officer who testified to overhearing him say these words in one of the many court cases that followed – over 200 arrests were made that day – was in fact not the officer who had arrested him. No such words were ever uttered, my dad insisted. In reality, he had instigated an impromptu sit-down in the middle of Regent Street and then complained about the rough handling of his five-month pregnant wife (my mum) by a completely different officer. Come the court appearance, as family legend has it, my dad defended himself and was complimented by the judge, who suggested he retrain as a barrister. Ultimately, though, he was found guilty and fined £15, which his fellow students at Regent Street Polytechnic paid on his behalf when he refused to.

This was the story my dad liked to tell, a wry smile curling the corners of his mouth. The story would end with the recollection of a fellow protester he met in the back of the police van that day, who told him he had been charged with

‘kicking a policeman in the groin’, even though he was physically incapable of doing so owing to a club foot. ‘Don’t tell anyone that until the day of the trial,’ my dad had suggested. But the man couldn’t hold it in that long, and when the police returned to the van, he complained and they simply changed the charge to something else.

What my dad didn’t tell us – something my mum only told us recently – was that his arrest that day in March 1968 followed him around for years. On securing a post as a senior lecturer at Chesterfield College five years later, for instance, plain-clothes CID officers visited both his future place of work and the tiny farming village he planned to move into, to warn co-workers and locals about the man about to enter their midst. Indeed it is no surprise that nearly five decades later, my family is still referred to in said village as ‘the communists’.

From Boudica’s Rising, through Peterloo, to the woodlands around Newbury and beyond, the quashing of unrest is something the British don’t do by halves. Every tactic has been tried and, in many cases, perfected.”

This case is mild, of course, amusing to the point of quaint. For, as many of the stories in this collection will attest, the history of British resistance is littered with much more violent and unlawful crackdowns than a mere creative use of the charge sheet or a spot of minor surveillance. From Boudica’s Rising, through Peterloo, to the woodlands around Newbury and beyond, the quashing of unrest is something the British don’t do by halves. Every tactic has been tried and, in many cases, perfected: torture, capital punishment (for treason), sabre-wielding cavalry charges, domestic espionage, entrapment, mass shootings, deportation (for the swearing of oaths), the deployment of troops and warships to British ports, plain-clothes snatch squads, Special Patrol Groups, ‘kettling’, even the use of improvised weaponry. Perhaps the reason why the British haven’t witnessed a revolution since the 17th century – and have an international reputation for being mild, moderate, even biddable – is simply that we police resistance ‘better’ here.

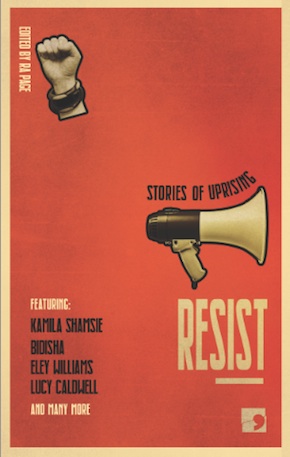

In putting this anthology together, two themes certainly emerged in the protests authors chose to write about: firstly the extraordinary and frankly creative lengths to which British security services have gone to ‘manage’ resistance; and secondly the growing institutional hostility and wider climate of intolerance that has often coincided with these extreme policing methods. Authors were presented with a long list of historical British protests to choose from, as well as the opportunity to work with a historian specialising in the protest in question, or an eyewitness who’d been there. Unlike in this book’s predecessor, Protest: Stories of Resistance, where many of the chosen movements seemed to cluster together around wider moments of social progress – what the Welsh language activist Ned Thomas called ‘awakenings’ – this time many of the authors chose to explore the flip side to that history; times when, instead of moving things forward, people rose up simply to stop them slipping backwards.

Among such rearguard actions explored in this anthology are the Cato Street Conspiracy (which responded to the oppressive Six Acts that followed Peterloo), the Battle of Cable Street (a response by the Jewish community, trade unionists and communists to Mosley’s blackshirts mobilising in East London), the Notting Hill Riots (the black community’s response to racist attacks by fascist-inspired Teddy Boys), and the Southall Riot (a response to the provocative staging of a National Front meeting in the heart of an Indian community). Whether successful, proportional or legitimate, each protest is open to ongoing reappraisal. But what is worth remembering in any context is what exactly these protests were trying to stop us from sliding into.

One of the differences between democratic socialism and neoliberalism is that the latter implies that the social contract (as originally conceived, between the state and the individual) is not enough.”

Before his death in 2000, the activist Tony Cliff often suggested that ‘the period we are living in is like a re-run of the 1930s but with the film running more slowly.’1 A seemingly intractable, decades-long economic crisis had led to the widespread deployment of racist scapegoating as a deliberate tactic to divide and weaken the working class in order to ensure they, and not the beneficiaries of capitalism, continued to pay for this crisis.

For many, this is too extreme an analogy. But it’s interesting to consider the scapegoating Cliff refers to in the current climate. Filmmaker Daniel Renwick, in his afterword to Julia Bell’s Grenfell Tower story, goes straight to the philosohical core of what we believe underpins society in trying to understand what went wrong: the social contract. One of the differences between democratic socialism and neoliberalism is that the latter implies that the social contract (as originally conceived, between the state and the individual) is not enough. It’s not enough that individuals’ rights need protecting in return for their law abidance; corporate interests need a voice too. In practice, these interests are always brought into the negotiations by stealth; the market needs to be free, so neoliberalism implies, in a way that individuals don’t. And the best way to understand corporations, legally and psychologically, is to regard them as ‘like people’. Thus corporations enter the social contract not as a third seat at the table, but as part of our seat – they become effectively the ‘best of us’, enjoying all of our rights, but fewer of our restrictions. (How often have the opinions of small-businessmen been granted privileged airtime in public debates, over and above mere members of the public?)

Meanwhile, the ‘worst of us’ slowly get removed from the contract. Rather than being citizens automatically, by virtue of us being human beings, we begin to learn (under neoliberalism) that we have to qualify first – rather like the cadets in Paul Verhoeven’s Starship Troopers have to earn their citizenship through life-threatening tours of duty. Rights thus transform, in the neoliberal logic, from things that we’re born with, to things we might be rewarded with if we deserve them. This removal of the undeserving, the ‘worst of us’ is something that can be seen historically in multiple contexts, as well as, sadly, the present. Right now it’s taking place on many fronts: from the mistreatment of those who simply lack the right paperwork, refugees (who can be detained indefinitely in UK removal centres, and therein enjoy fewer rights than convicted criminals), to the media scapegoating of so-called ‘benefit scroungers’ (not just undeserving individuals, but undeserving types of individuals, somehow congenitally predisposed to ‘not pulling their weight’). A third category who have started to be ‘othered’, in the public imagination at least, is protesters.

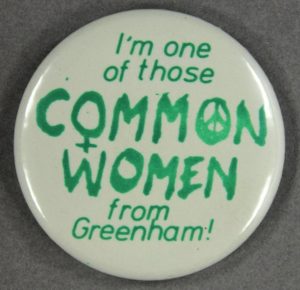

This process is perhaps the subtlest. It begins with the emphasis the media places, in its reporting of protest, on very specific details: the strangeness of protesters’ clothes, their hairstyles, or other aspects of their lifestyles. Whether this was in relation to the Greenham Common women of the 1980s, the anti-roads protesters of the 1990s (made famous by ‘Swampy’), or the Occupy movement of the 2000s, the media’s ‘othering’ of them was a deliberate attempt to create a public perception that these people somehow lived ‘outside the law’ – as if such a place exists – thus paving the way for them to be treated differently to ordinary citizens. Early examples of how this cultural scapegoating might manifest in legal practice include the increasingly regular prosecution of protesters under counterterrorism legislation (that special set of legal exceptions put aside for the most ‘othered’ of all citizens).

In a climate where the ‘us’ has been dissected, in the public consciousness, into different categories – the deserving, the especially deserving (business elites), and the undeserving (‘others’) – it’s very easy for the scapegoating that Cliff talks about to be institutionalised. Casting an eye over the stories in this book, we realise people working in law enforcement seem surprisingly willing, at these particular moments in history, to treat the ‘others’ in the fields of protest with an almost complete lack of compassion. Just as people working today in immigration detention, the Home Office, or benefits means testing, have also been regularly accused of callousness.

Institutionalising this ‘othering’ is a three step-process, it seems. First, you need years of almost daily scapegoating by the popular media (as protests are occasional, saturation hasn’t been reached here); secondly, you need a demagogue who publically and privately elevates the status of officers working in enforcement over and above other public sector employees (in Trump’s case, his constant fawning over ICE agents); finally, you need a coded signal to those working in enforcement, by said demagogue, implying an unspoken mandate to implement the policy, cutting through the nanny state’s red tape, or the ‘snowflakes’ in the courts or parliament.

Once the first two steps are in place, it doesn’t take much of a signal – a mere nod or wink, in fact – to finalise the institutionalisation of these attitudes. Theresa May’s use of the phrase ‘hostile environment’, as well as other nods, like her promise to axe the European Convention on Human Rights, were all that was needed for the Home Office to institutionalise the tabloid’s hatred of refugees. Thatcher’s pre-election ‘fear of being swamped’ was snapped up by the Metropolitan Police Force, who even named their operation ‘Swamp 81’ in deference to her. The slighter the nod, the subtler the wink, the harder it is for journalists to trace it back to the top. But where journalists fail in this tracing, historians usually succeed.

Could it be that our institutions are not just increasingly hostile to ‘othered’ groups, but are developing an international consensus with other countries’ agencies as to how to treat them?”

In The Origins of Totalitarianism, Hannah Arendt noted that sufficiently elevating the prestige attached to the law enforcement agencies in your country (stage 2) can lead to police forces in other countries taking their cues from your agencies, rather than from their own governments. ‘Long before the outbreak of the war,’ Arendt writes, ‘the police in a number of Western countries, under the pretext of “national security,” had on their own initiative established close connections with the Gestapo and the GPU [Russian State security agency], so that one might say there existed an independent foreign policy of the police.’ By way of example, she adds: ‘If the Nazis put a person in a concentration camp and if he made a successful escape, say, to Holland, the Dutch would put him in an internment camp.’

Could it be that our institutions are not just increasingly hostile to ‘othered’ groups, but are developing an international consensus with other countries’ agencies as to how to treat them, irrespective of each individual government’s policies? In as much as these questions of treatment involve logistical challenges (that can be learned from and shared), the answer is understandably yes. But the ethical question – how is the state responsible for them? – is too often informed by a combination of tabloid headline writers, and one particular foreign nation’s more televised and media-ready figurehead.

Against pluralism, we see a narrowing down of what constitutes ‘us’, and the eviction of the ‘less deserving’ from the social contract, until it only applies to the ‘best of us’ and those willing to be strapped and bound to a hardening central core – like wooden rods around an axe in a fasces. And as Arendt noted, the figurehead at the top of the central shaft doesn’t even need to be our figurehead.

In case you’re wondering what I’m talking about here, I’ll spell it out. Fascism.

It’s easy to see patterns across different countries’ responses to the so-called ‘migrant crisis’,2 but less easy to see them in their ethical considerations in security responses to protest. Perhaps this is because we’re looking at the wrong figurehead on this issue. For Putin – sixteen years a KGB foreign intelligence officer – there’s no such thing as a genuine protester, or an organic protest. For decades during the Cold War, Russian intelligence prided itself on its ability to engineer protests in other countries at the drop of a hat. Recently unsealed KGB files from Yuri Andropov’s time as chair (1967–82) show agents claiming to be able to mobilise protests of up to 20,000 people outside the US Embassy in India for a set fee (equating to a quarter-rupee per protester).3 This is what protest is for Putin: a paid-for foreign intervention. He saw evidence of foreign protest-sponsorship in the Orange and Rose revolutions in Ukraine and Georgia (2003, 2004). He exposed it with his first big hacking success in February 2014, when his agencies released a taped phone call between Victoria Nuland (America’s Assistant Secretary of State) and the US ambassador to Ukraine, in which they openly picked their preferred opposition leader to replace President Yanukovych after the anticipated revolution. And he fought fire with fire when he set in place counter-insurgency youth groups such as Nashi and the Young Guard of United Russia, who, when the time came, could simply be paid to meet ‘democracy’ protests on home turf with counter-protests. (Resemblances between these groups and the Hitler Youth are not entirely accidental).

Given the way the British government seems to be aping everything the White House does right now, we shouldn’t be surprised when allegations towards protesters, saying they’re agents or paid to protest, start flying here.”

But why am I talking about Russian intelligence tactics in a book about British protest? Well, until not long ago, the idea of protesters in the West being paid to go out on the streets would have been laughable. But that’s exactly what Trump claimed in October 2018 when thousands of women descended on Washington to protest the swearing in of alleged sexual assailant Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court. ‘Paid professionals’ Trump called them in a tweet that also implied George Soros was the one paying, doubling-down four days later when he claimed the same people were now protesting because they hadn’t received the cheques yet.

Putting aside any mental instability on Trump’s part, it’s interesting to ask: where did he get this idea from? Whether it was from the dark corners of the web, where almost untraceable conspiracy theories can be planted, or whether it’s much more directly, from one of his unaccompanied one-to-ones with Putin, it doesn’t ultimately matter. In the final analysis, it’s an attitude to protest that has its roots in state espionage. Nor do we even need theories of Russian hacking or the alleged ‘pee-tape’ leverage over Trump to see why this attitude towards protest should be shared so easily, between these demagogues: to quote the historian Howard Zinn speaking in 1970, ‘Nixon and Brezhnev have much more in common with one another than we have with Nixon… That’s why we are always surprised when they get together – they smile, they shake hands, they smoke cigars, they really like one another no matter what they say.’4 Thus we also shouldn’t be surprised when one demagogue’s Cold War-influenced thinking towards protest hops the pond and becomes another’s. And given the way the British government seems to be aping everything the White House does right now, we shouldn’t be surprised either when allegations towards protesters, saying they’re agents or paid to protest, start flying here.

In short, if protesters aren’t ‘hippies’, living outside the law, they’re the post-Cold War equivalent of ‘commies’, agents of a foreign power, traitors. Either way, they’re not ‘us’.

To quote Jacob Ross, a riot, or as he prefers, a ‘rising’ should never be dismissed as a mere act of mass criminality. It is rather a ‘renegotiation of the social contract.’”

Fighting fascism is far from the only battle preoccupying the protesters in this book. It merely seems to be something ‘in the air’ at the moment, as bookshops get raided by far-right thugs, parliament is shut down unlawfully for obvious political ends, and nationalists continue to reap the rewards of a referendum result won (in part) by the modern equivalent of tabloid journalism, targeted social media misinformation. The types of protest featured vary widely, from traditional strikes, marches and demos, through to military sabotage, civil disobedience, even letter-writing campaigns. Some might question how broadly we’re defining resistance, here, especially given our decision to include protests that, by accident or design, ‘descended’ into violence. The reason we took this expansive definition is to avoid the filter of modernity blinkering us from actions that may prove entirely political as time moves on. A riotous event that took place sufficiently long ago, like the Battle of Cable Street, is much easier to file under ‘protest’ than, say, the anger on Tottenham High Road that sparked the August 2011 riots. Of course, a distinction can be drawn between taking to the streets to call for a change in the law, and taking to the streets to protest the methods by which law is enforced generally. The latter may be historically more prone to morph into a riot, but it’s not by any means the only type of protest that does morph into one. To quote Jacob Ross, a riot, or as he prefers, a ‘rising’ should never be dismissed as a mere act of mass criminality. It is rather a ‘renegotiation of the social contract’.5 What’s being negotiated isn’t a change in the law, but a change in who those laws are seen to apply to; it’s a reminder to the rest of society of whose rights should be protected by the law, who sits at the table. All of us.

From the introduction to Resist: Stories of Uprising (Comma Press, £14.99)

1 Grent, Nick & Richardson, Brian, ‘Blair Peach: Socialist and Anti-Racist’ (Socialist Worker).

2 Research is currently being undertaken by the project ‘Hostile Environments: Policies, Stories, Responses’ to document these commonalities.

3 Claire Berlinski, ‘Fruits from the Tree of Malice’, City Journal, Winter 2011.

4 ‘The Problem is Civil Disobedience’, speech by Howard Zinn, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, November 1970.

5 The Comma Press Podcast, Series 1, Episode 6: ‘The New Cross Fire & Brixton Riots with Jacob Ross and Stephen Reicher’.

Ra Page is the founder and editorial manager of Comma Press. He’s the editor of numerous anthologies, including The City Life Book of Manchester Short Stories (Penguin, 1999), co-editor of The New Uncanny (winner of the Shirley Jackson Award, 2008) and Litmus, voted one of 2011’s books of the year by the Observer. Between 2004 and 2013 he was also the coordinator of Literature Northwest, a support agency for independent publishers in the region (until it formally merged with Comma). He also coordinates Comma Film, an ongoing film adaptation project which regularly commissions filmmakers and animators to adapt short literary texts (poems and short stories). He read Physics and Philosophy at Balliol College, Oxford and has an MA in English from the University of Manchester. Resist is published by Comma Press in hardback and eBook.

Ra Page is the founder and editorial manager of Comma Press. He’s the editor of numerous anthologies, including The City Life Book of Manchester Short Stories (Penguin, 1999), co-editor of The New Uncanny (winner of the Shirley Jackson Award, 2008) and Litmus, voted one of 2011’s books of the year by the Observer. Between 2004 and 2013 he was also the coordinator of Literature Northwest, a support agency for independent publishers in the region (until it formally merged with Comma). He also coordinates Comma Film, an ongoing film adaptation project which regularly commissions filmmakers and animators to adapt short literary texts (poems and short stories). He read Physics and Philosophy at Balliol College, Oxford and has an MA in English from the University of Manchester. Resist is published by Comma Press in hardback and eBook.

Read more

@commapress