Dolorosa

by Rodrigo Hasbún

“He is not a good writer, thank goodness. He is a great one.” Jonathan Safran Foer

It wasn’t an easy journey. From Santa Cruz, Monika had to take the main road for four hours to Concepción, and from there it was at least three more hours of ruinous dirt roads.

She drove with the radio on. Her shoulders and neck ached – not even sleep could ease the tension. And to make matters worse, she wasn’t sleeping more than three hours in a row. Her dreams tended to be bad and she often woke up screaming and crying. Inti had had the same problem, one more thing that united them. A cold shower usually brought her back to the world. Then she would do her exercises, eat something and start work. She wrote messages, planned meetings. She thought up new ways to get funds. How much would her father know?

Monika hadn’t seen another vehicle for half an hour. There’d be no need for her forged documents this time. She thought about last week’s losses. They’d intercepted Warmi, Miguel and Juan in Cochabamba and a fight had broken out, only ending when Warmi’s bullets ran out. Juan had managed to escape and Warmi asked Miguel to kill her before the soldiers did. Knowing she was right, he aimed at her heart and fired. When he heard them coming down the hallway he turned the gun on himself. He relayed all this to the press the following day. He hadn’t succeeded in dying. Monika didn’t know what the soldiers thought they would achieve by allowing him to make statements like that. Show how savage the extremists are? The girl, Warmi, was a Venezuelan trained in the GDR, he a Uruguayan. Juan, for his part, turned up dead two days later. They said he’d committed suicide. She didn’t want to imagine what they must have done to him before killing him, or how much information they’d got out of him, or how much they’d get out of Miguel.

There had to be moles. That was the only way they could have caught up with them, the only way they could have tracked down Inti eleven months earlier. Sometimes the enemy is closer than you imagine. He sneaks in and disguises himself as one of you, as your most loyal friend. She would have to learn to spot him in time, before there were any more killings. In recent weeks there had also been deaths on the other side: the editor of Hoy newspaper and his wife, as well as one of Barrientos’s ex-ministers. On the radio, two broadcasters began commentating on a football match between Bolívar and Wilstermann. She could never get her head around how the country carried on as normal in the midst of so much terror.

He froze, convincing himself that what he was seeing was real, and then strode towards her, hugging her tightly, instinctively, the moment he reached her.”

She looked into one wing mirror then the other, and estimated she would be there around one. There were still a couple of hours to go. It wasn’t an easy journey. It was even harder than she’d imagined. Everything will be fine, Monika told herself. In the long run, everything will turn out OK.

***

Her father was with two men. She stood in the entrance of the house which sat at the top of a hill. He was giving instructions, waving his arms dramatically while the others nodded. They were clearing a decent-sized patch of land and now they’d come up against some problems with a tree they were trying to cut down.

It would make the perfect spot. It was secluded, and not far from there was some unmapped terrain. That’s what she was thinking when her father spotted her. He froze, convincing himself that what he was seeing was real, and then strode towards her, hugging her tightly, instinctively, the moment he reached her.

They kept the conversation casual in the kitchen. In an attempt to ease the growing tension Monika apologized for not having warned him she was coming, and asked if she could stay for a few days.

“You can stay for as long as you like,” was her father’s response.

She thought he looked well. He had recently turned sixty-one but seemed considerably younger, despite his grey hair and beard. He showed her around the house. It was spacious and she was surprised to see how well kept it was. She was even more surprised to find one of the walls in the dining room covered in old photos. Her father had never been particularly given to nostalgia, a quality she had happily inherited.

“What are they doing outside?”

“They’re making a runway. First we’ll clear a decent strip of land, then level it and then mark it out, and voilà.”

“Why?”

c. 1958″ width=”300″ height=”240″>“Well, you have to mark it out so that—”

c. 1958″ width=”300″ height=”240″>“Well, you have to mark it out so that—”

“No,” she interrupted, “why a runway?”

“Ah,” he said. “I’m going to start selling my produce to an export business. The return’s better, but they run a tight ship. The runway will speed up the traffic. And another thing,” he boasted, “every now and again my friends visit me in their light aircraft. They don’t even come from far. The General’s hacienda is a stone’s throw from here.”

“Colonel,” she corrected him. “I didn’t know you were friends.”

“Have you eaten?”

Monika shook her head.

In his company she no longer felt in control. Her strength deserted her, she lost years in a matter of seconds. At thirty-two she regressed to being a teenager, a little girl who didn’t know what to do with herself. She had to process this information, to accept that perhaps Dolorosa was less safe than she had imagined.

She saw him go onto the terrace where he called out a name. A moment later a small woman with Guaraní features appeared and greeted her submissively.

Nothing made Monika feel more uncomfortable than servitude. It was precisely servitude that reaffirmed in her the need to keep up the fight.

“Jacinta, what could you whip up for my daughter?”

“Whatever the young lady likes, Don Hans.”

“What do you fancy?” her father asked her.

“Anything at all,” she answered. “Whatever’s easiest.

***

In the afternoon he gave her a tour of the land. He had large cornfields and hundreds of cows, chickens and goats. They crossed paths with five of his employees along the way and she asked him if they lived here. He said they had houses over to the east. To the west there was nothing, just wild bush that also belonged to him. He had two thousand hectares in total. She was impressed by how her father had managed to achieve all this on his own, by how he’d reinvented himself so convincingly.

The moment they got back, she went to inspect the photo more closely. They were explorers, but looked like guerrillas. They all seemed happy apart from her father, who was the only one without a smile on his face.”

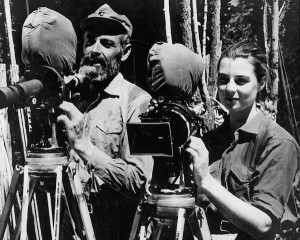

They walked for hours, barely saying a word to one another. It was like being back in the rainforest, far from the world and the horrific things that happen in it. Monika was still thinking about one of the photos she’d noticed earlier on the dining-room wall. She couldn’t recall having seen it before, and had certainly never owned a copy. It was taken at the end of the expedition, when Heidi and her mother had come along to catch up with them. All three of them were in the frame, as well as Burgl, Rudi and her father. Now, without looking at it, she couldn’t remember their expressions or what was behind them.

The moment they got back, she went to inspect the photo more closely. They were explorers, but looked like guerrillas. They all seemed happy apart from her father, who was the only one without a smile on his face. She had revered him madly on that trip: his courage, his passion, his will.

“It’s one of my favourite photos,” she heard him say.

She turned and looked at him. Twelve or thirteen years had passed since the end of the expedition. At times it seemed like double that, at others not even half.

“Ready for supper?”

Monika let out a laugh.

“What?” her father asked.

“I’ve only just eaten lunch,” she said.

“Hours ago,” he said.

“I’m fine.”

“You look drained.”

“I’m fine,” Monika repeated.

“I’m not talking about the food,” her father said. “I mean in general, I’ve never seen you like this. Jacinta has already fixed up your room, go and sleep for a while.”

She went out to the car for her rucksack and also took the opportunity to fetch the revolver she had under the seat. Back in her room, she slipped it under the pillow and took off her boots. She did a few exercises before getting into bed and woke up seven hours later. It had been years since she’d slept for that long, and she had to check her watch several times to convince herself that it had really happened. A few minutes later, without even realizing, she’d nodded off again.

When Monika left her room at six-thirty the following morning her father was already up and waiting for her at the table. Jacinta appeared with a glass of mandarin juice, offered her some oatmeal, and then, having served her some, asked how she liked her eggs. Monika was distracted over breakfast, absorbed in the twenty or so photos on the wall that summed up their lives.

“I tried to wake you up last night for supper but you were dead to the world,” her father said.

He was trying to be nice. Their relationship had always had its ups and downs. There had been times when they had stopped speaking – when Monika got married or when he made his relationship with Burgl official – but there had also been moments of absolute intimacy.

She asked after Burgl.

“She’s well,” he said.

“Are you still together?”

It took a few minutes for her father to reply that he didn’t know, and that Burgl had been away for almost three years. They wrote to one another every fortnight, and spoke on the telephone from time to time. For now they didn’t have any plan to start things up again.

“And you?” he asked.

This was always the risk if they were going to play at being close again.

Monika thought about Inti. She recalled her days in Havana when she met him. She recalled the long walks they took together, the conversations, the thrill. With her he was no longer the reserved man all the others saw.

“I’m single,” she replied.

“Your husband isn’t a bad man, but he wasn’t right for you,” he said. “I knew all along that it wouldn’t work.”

Jacinta came in, rescuing them. She took away the plates, smiling, and a little while later they could even make out her voice as she sang to herself in the kitchen.

Her father had a few matters to attend to – they would see each other for lunch. Being alone often meant losing her sense of order, and that idea scared her. She decided to take a better look around the land.

“Is is quiet around here?” she asked Jacinta on her return.

“It doesn’t get any quieter than this.”

“You live in one of the small white houses, do you?”

“With my family, yes. I’m making majao, señorita. Do you like it?”

“How could I not?” Monika replied.

Back in her room she tried and failed to concentrate. The city and the war had vanished in less than a day, this place seemed like another planet. The enemy gets into your head, tries to convince you there’s no sense in fighting, makes you believe you could abandon the fight, ignore what matters most, go back to your life from before. She hated herself for thinking these things, for her lack of seriousness.

As a means of self-preservation she thought about Inti, about his determination and how he spent months on the run. The news of the ambush had filled her with rage and pain but she hadn’t let herself grieve for long. She also thought about her trips through Europe, years earlier. On her way through Freiburg during one such trip she met up with Reinhard. She’d intended to tell him she had been pregnant with his child, but in the end chose not to. He seemed a shadow of his former self, an utterly defeated man.

‘They won’t come near the house,’ she said. They would live in the bush… Nobody need find out, not even his workers or the locals.”

A feeling of desperation began to stir inside her. Monika didn’t know how to fight it, had never known. She rooted around in her rucksack for her book. It was a collection of Che’s essays and speeches published by Rowohlt. It felt strange reading them in translation.

Her father came back at midday. She heard him in the living room speaking with Jacinta in his stilted Spanish. Then Jacinta knocked on the door to tell her lunch was ready.

“Why are you here, Monika?” he asked her a few days later. They’d been walking in silence up until that point. Now he had stopped and was looking at her. He wanted an instant reply. His old, intransigent ways were rearing their head again.

More than two years had passed since they’d seen one another. It must have been unnerving for her father, her being there. It was for her. It hadn’t been an easy decision to visit him.

She was going to be direct, as direct as he was.

“I came to ask you for something,” she said.

“I’m listening.”

She took a deep breath and said she needed to ask him if he would let a few of her comrades live in Dolorosa for a while.

“I don’t understand,” her father said.

“They won’t come near the house,” she said. They would live in the bush. There, where they stood talking. The group were in urgent need of a safe place. Nobody need find out, not even his workers or the locals.

“A place for what?”

“To hide out for a while and train.”

“The Bolivians have always been good to us,” he said, cutting her off.

“This is for the Bolivians,” she said. “There’ll be new raids. The guerrillas need to train in real conditions.”

“Do you realize what you’re asking me to do?”

“I’m asking you to help your daughter.”

“Wars are fought in cities, Monika.”

“They wouldn’t stand a chance in the city.”

“And in the middle of nowhere they would? Haven’t you people learnt your lesson yet?”

It was hard to believe her father was so well informed, that he was saying these things, that they were both keeping their cool.

“Let’s go back to the house. It’s getting late,” he said.

“It wouldn’t affect you in the least,” she said.

“You don’t know what you’re saying.”

“I’m saying a few comrades using your land wouldn’t affect you.”

“I don’t want any part in your idiocies or your violence or your deaths,” he said, now with another tone entirely, and staring at her.

She had been naive to expect anything from her father.

“Let’s go back, we’ll carrry on talking later,” he said.

“I want to know if it’s a definitive no.”

“The time for these things has been and gone,” he said.

“That’s a no?”

“We’ll talk later. Let’s go back to the house.”

***

Half an hour later they were screaming at each other in the living room. “You’re nothing but a lackey to pigs in suits. A filthy fascist!” was the last thing Monika said before grabbing her keys, rucksack and revolver from the room, then leaving without a word.

That scene would remain with him for the rest of his life. He would replay it obsessively in his mind over and again: his darling daughter insulting him, the sound of the car engine fading into the distance.

The next time he saw her was on a poster in La Paz. The army was offering a hundred thousand pesos for her, dead or alive.

Extracted from Affections, translated by Sophie Hughes.

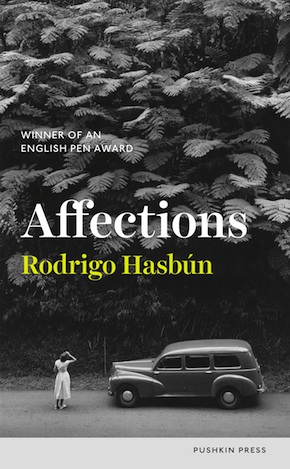

Rodrigo Hasbún is a Bolivian novelist of Palestinian descent born in 1981. He is the author of two novels and a collection of short stories. In 2007 he was selected by the Hay Festival as one of the Bogotá 39, and in 2010 he was chosen as one of Granta’s Twenty Best Spanish writers under the age of 35. His work recently appeared in the Latin American issue of McSweeney’s, edited by Daniel Galera. Affections, his second novel – loosely based on the lives of German filmmaker and explorer Hans Ertl and his daughter Monika, who fought with Bolivian Marxist guerrillas and became known as ‘Che Guevara’s avenger’ – is published in the UK by Pushkin Press. Read more.

Rodrigo Hasbún is a Bolivian novelist of Palestinian descent born in 1981. He is the author of two novels and a collection of short stories. In 2007 he was selected by the Hay Festival as one of the Bogotá 39, and in 2010 he was chosen as one of Granta’s Twenty Best Spanish writers under the age of 35. His work recently appeared in the Latin American issue of McSweeney’s, edited by Daniel Galera. Affections, his second novel – loosely based on the lives of German filmmaker and explorer Hans Ertl and his daughter Monika, who fought with Bolivian Marxist guerrillas and became known as ‘Che Guevara’s avenger’ – is published in the UK by Pushkin Press. Read more.

Author portrait © Martín Boulocq

Sophie Hughes is a literary translator and editor based in Mexico City. Her other recent translations include Iván Repila’s The Boy Who Stole Attila’s Horse (Pushkin Press, 2016) and Laia Jufresa’s Umami (Oneworld, 2016). Her essays, reviews and translations have appeared in publications including the Times Literary Supplement, the Guardian and the White Review.

@hughes_sophie