Double lives

by Peter Stamm

“One of Europe’s most exciting writers.” The New York Times

Even when I saw Lena onstage, I was shocked by her resemblance to Magdalena. But when she walked out of the hotel and stopped a few feet away from me, it took my breath away, and I felt paralyzed. She hesitated briefly, looked up and down the street, then, seemingly at random but nonetheless purposefully, she struck out for the center. She was walking fast and, barely stopping to think, I set off after her. She looked just like my Magdalena when she accompanied me to Stockholm sixteen years ago now, with a swaying, almost skipping walk, and the same facial expression, a mixture of astonishment and amusement. Sometimes she would suddenly crane her neck and look up, as though she had heard something or was looking for something, then her expression became serious, and for a moment it was as though she was listening out for something only she could hear.

We had been together for three years, sometime I had left my old apartment and moved in with her. By now she wasn’t attached to a particular theater anymore, and I was only rarely turning out copy for the ad agency and was starting to write for newspapers and magazines instead. I had never quite given up the desire to write seriously, though I didn’t do much to realize it either. The text about Magdalena and my life hadn’t seemed to lead anywhere. Eventually I told her about it, claiming our life was too uneventful for it to be made into literature. Why write it all down? I asked, after all, we’re living it. In reality I was afraid of Magdalena becoming a stranger to me again, and that the fictive Magdalena could supplant the real one. Magdalena seemed to be happy that I’d given up the idea. She encouraged me instead to write dramatic texts, with parts in them that she could play. But I didn’t seem to be able to manage that either. I like you best when you’re not playing a part, I said. It was true, I didn’t enjoy seeing her onstage, because I didn’t want to have to see that she was capable of being a completely different person, that our love was not the only possibility in her.

Even when we were living together, I sometimes had palpitations when she came home later than she’d said, and suddenly stood there in the apartment, as though setting foot there for the first time.”

Even when we were alone together, I sometimes had the sense that she was playing a part, maybe not deliberately, but because she couldn’t help it. Perhaps it was that that wouldn’t let me go, the feeling I could never get really close to her, never see through her, never possess her. I puzzled over what I might be to her. The only certain proof of her love was that she stayed with me. When we went to parties or premieres together, she was swarmed by men who were better-looking than me, who were cleverer and funnier and above all more successful and had more to offer her than I did. She would flirt a little with one or other of them, but sooner or later she would always come to me and say she had had enough, and could we go home now. There was something painful and consuming about my love for her. Even when we were living together, I sometimes had palpitations when she came home later than she’d said, and suddenly stood there in the apartment, as though setting foot there for the first time.

One day Magdalena showed me an advertisement in the paper. They were looking for television writers for a new series. That would be something for us, don’t you think? You write the scripts, and I’ll play the leads. We’ll be rich and famous, like Marilyn Monroe and Arthur Miller. Well, you know what happened to them, I said, but nevertheless I applied. I devised a couple of plots, wrote some trial scenes and sent them to the producer. I was invited to meet them, and was told my ideas were not filmable, but they saw some potential in my writing anyway. I got to work again, and proposed a series set in a meteorological research station in the Alps. For a few months, I was in regular back-and-forth with the TV people. They kept pressing me to more commercial subjects, sent me examples of screenplays they liked, and gradually cut everything from my scenes that I thought was original or clever. At least I wasn’t badly paid for the work, and eventually, along with a director and an editor, I got an invitation to participate in a master class in Stockholm, to be led by an American TV writer.

I had hoped to maybe see a bit of the city, instead I spent whole days with writers from half of Europe cooped up in the conference room of an anonymous hotel, listening to the American hold forth about story lines and plot points, and trying to get us going with his phony enthusiasm. No one can stop you now except you yourselves, he said, and passed around memos of tips and tricks and claimed that if you only followed his advice you would become a celebrated TV writer. I asked myself what such a man was doing leading workshops in so-so hotels in Sweden if he was that clued in to the secrets of successful scripts. Everything was getting me down, the yammering American, the participants who eagerly took down his every word, the two TV people there with me who treated me as the tyro I suppose I was. Magdalena spent her days in the city and when we met up at the end of the afternoon, told me what she had been up to. In the evening all the workshop participants, plus leader, ate dinner together. The first evening Magdalena joined us, but she seemed to be even more bored than me, and when we got up to our room at midnight, told me one author was plenty for her, she would eat dinner alone tomorrow, and maybe take herself to the theater or the cinema.

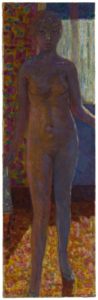

I went into a corner and pretended to be examining a painting, a nude by Bonnard, but all the time I was peering around at her.”

While I was trailing Lena, I had asked myself whether someone might have followed my Magdalena sixteen years ago; if not only did I have a doppelgänger, but I might be someone else’s, links in an endless chain of identical lives running through time. I tried to remember what Magdalena had told me about how she spent her days, whether she had visited the forest cemetery with a man who had told her some crazy story. But would she even have told me? Would she have believed him? Did Lena believe me?

Pierre Bonnard: Nude in Counter-light, 1920. Photo © Anna Danielsson, National Museum Stockholm

She went into a few stores, looked at dresses, shoes, furnishings. She bought a red rocking horse, a couple of glass candleholders, and a T-shirt bearing the legend I ♥ SWEDISH GIRLS. She ate her lunch at a small café. Afraid to lose her from sight, I waited outside and watched through the window as she conducted a laughing conversation with the waitress, who then gestured, as though to point her the way. After lunch, Lena chose her direction with even greater purpose, and led me to the National museum, a classical building facing the water.

There were very few visitors, and I followed her through the quiet rooms. The pictures were hung densely, often one over the other, and some of the rooms contained sculptures and partition walls with even more paintings hung on them. Lena didn’t seem to be that interested in art. She crossed the rooms without stopping, as though absolving a show-jumping course, or on the lookout for something or someone. The only time she stopped was in front of a few still lifes. After she had moved on, I stopped to look at the pictures, which were by a Dutch seventeenth-century master, and depicted the cannily arranged booty of successful hunting expeditions, dead foxes, game birds, and hares. One picture showed a couple of hounds, and another a cat stretching out her claws in the direction of the dead birds.

Lena had gone on, but I caught up to her quickly enough. She had sat down on a bench a couple of rooms farther on, looking abstractedly in front of her. She seemed not to have noticed that anyone else was in the room. I went into a corner and pretended to be examining a painting, a nude by Bonnard, but all the time I was peering around at her. Finally, she stood up, turned on her heel, and marched back through all the rooms, out of the museum, and back to the hotel. I was completely exhausted, not so much by the rapid pace as by my feelings. I scribbled a brief note in the lobby and asked the porter to take it up to Lena’s room. Please come to the forest cemetery tomorrow, two p.m. I have a story I want to tell you.

From The Sweet Indifference of the World, translated by Michael Hofmann

Peter Stamm was born in 1963, in Scherzingen, Switzerland. He is the author of the novels Seven Years, On a Day Like This and Unformed Landscape, and the short-story collections We’re Flying and In Strange Gardens and Other Stories. His prizewinning books have been translated into more than thirty languages. He was shortlisted for the Man Booker International Prize in 2013, and in 2014 won the prestigious Friedrich Hölderlin Prize. He lives in Switzerland. The Sweet Indifference of the World is published by Other Press and Granta Books in hardback and eBook.

Peter Stamm was born in 1963, in Scherzingen, Switzerland. He is the author of the novels Seven Years, On a Day Like This and Unformed Landscape, and the short-story collections We’re Flying and In Strange Gardens and Other Stories. His prizewinning books have been translated into more than thirty languages. He was shortlisted for the Man Booker International Prize in 2013, and in 2014 won the prestigious Friedrich Hölderlin Prize. He lives in Switzerland. The Sweet Indifference of the World is published by Other Press and Granta Books in hardback and eBook.

Other Press

Granta Books

@autorstamm

Author portrait © Anita Affentranger

Michael Hofmann is a German-born poet and translator. He has translated the work of Gottfried Benn, Hans Fallada, Franz Kafka, Joseph Roth and many others. In 2012 he was awarded the Thornton Wilder Prize for Translation by the American Academy of Arts and Letters. His Selected Poems was published in 2009, Where Have You Been? Selected Essays in 2014, and One Lark, One Horse: Poems in 2019. He lives in Florida and London.