Down on Disneyland

by Elisa Shua DusapinDOMED BLUE CEILING, a phantom ocean. The Little Mermaid hangs from a wire, waving her hands in greeting, her tail swishing sinuously in her wake. Her stomach bulges from the harness beneath her bodysuit. Down on the ground, visitors brandish cameras, contorting themselves to keep her in their sights. A puff of smoke and Triton, king of the waves, surges forth. A robot, not a living actor like the mermaid. His voice booms out a warning to his daughter: ‘Moray eels.’ Ariel screams, another puff of smoke, she spins one last time and disappears. Darkness.

—

I find her stroking a Bambi figurine.

‘Do you like Bambi?’ I ask hopefully.

She nods.

‘Would you like me to buy it for you?’

‘No, that’s okay.’

‘I’ll give it to you as a gift. I’d like to.’

‘But I don’t want it. His mother’s dead and his father goes away somewhere at the end, and we don’t know where he’s gone.’

‘That’s because he’s old. He goes away to die.’

‘I know that,’ she says scathingly.

Snippets of the story come back to me. It wasn’t my favourite Disney tale, I found it irritating, the timid little fawn afraid of his own shadow.

‘I don’t want it!’ she says again as I head towards the cash desk with the figurine.

‘I’m buying it for my grandmother.’

She stares at me in disbelief. I finish paying and stuff the figurine into the bottom my bag, holding it close under my arm to keep it out of the rain. Mieko hasn’t taken her eyes off me.

‘It’s just to remind her of when I was little,’ I say, thinking of the evenings my grandmother and I used to spend together watching the videos I brought with me from Switzerland – The Lion King, The Little Mermaid, Sleeping Beauty – it was something we both enjoyed.

‘All children play with their grandmothers…’

‘I didn’t,’ she mutters, eyes cast down.

I doubt my grandfather would object to me showing her round the Shiny. It’d certainly be less bother and much less expensive than coming all this way out of the city to Disneyland. Even so, I don’t want to make any promises.”

I try and make amends. I wasn’t exactly playing with my grandmother, I say, it was more a way of being together, and besides, I didn’t see her very often, only during the holidays, and my grandfather was always working at the pachinko parlour, from morning till night.

‘The pachinko parlour,’ Mieko says, interrupting me. ‘That’s where I’d like to go.’

I laugh. Does she even know what a pachinko parlour is? She rolls her eyes. Obviously, everyone knows about pachinko parlours, they’re everywhere. She’s never been inside one. That’s what she wants to do with me.

‘They’re not for children you know, it’s not a children’s game.’

‘I know.’

She stares at me earnestly. I doubt my grandfather would object to me showing her round the Shiny. It’d certainly be less bother and much less expensive than coming all this way out of the city to Disneyland. Even so, I don’t want to make any promises.

‘If you like, one day… Maybe we could, yes.’

Mieko smiles. At long last, I think to myself, she looks like a normal kid.

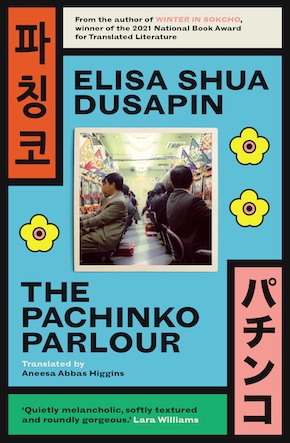

from The Pachinko Parlour (Daunt Books, £9.99), translated by Aneesa Abbas Higgins

Elisa Shua Dusapin was born in France in 1992 and raised in Paris, Seoul and Switzerland. Her first novel Winter in Sokcho (Hiver à Sokcho) was awarded the National Book Award for Translated Literature, the Prix Robert Walser and the Prix Régine Desforges and has been translated into twenty-three languages. The Pachinko Parlour was awarded the Swiss Literature Prize and has to date been sold into eleven languages. The English translation by Aneesa Abbas Higgins is published by Daunt Books in paperback and eBook.

Elisa Shua Dusapin was born in France in 1992 and raised in Paris, Seoul and Switzerland. Her first novel Winter in Sokcho (Hiver à Sokcho) was awarded the National Book Award for Translated Literature, the Prix Robert Walser and the Prix Régine Desforges and has been translated into twenty-three languages. The Pachinko Parlour was awarded the Swiss Literature Prize and has to date been sold into eleven languages. The English translation by Aneesa Abbas Higgins is published by Daunt Books in paperback and eBook.

Read more

@ElisaDusapin

@DauntBooksPub

Aneesa Abbas Higgins is the award-winning translator of Winter in Sochko, and has translated works by Nina Bouraoui, Vénus Khoury-Ghata, Tahar Ben Jelloun and François Garde. Her translation of Ali Zammir’s A Girl Called Eel was awarded the Scott Moncrieff Prize. Her work has also appeared in Asymptote and Words Without Borders.

free99656.wordpress.com

@aneesa50abbas