Elixirs and poisons

by Mika Provata-Carlone In the work of Ioanna Karystiani, a meeting between worlds takes place. Thought and matter come clashingly together. The old and the new accuse and forego one another. Memory and facelessness stare haughtily at each other. Meaning and incomprehensibility stagger us with their urgency and despair. Dignity tries to speak. It stutters, fumbles for the right words, the right feelings, images and gestures. Above all, it tries, with all its might.

In the work of Ioanna Karystiani, a meeting between worlds takes place. Thought and matter come clashingly together. The old and the new accuse and forego one another. Memory and facelessness stare haughtily at each other. Meaning and incomprehensibility stagger us with their urgency and despair. Dignity tries to speak. It stutters, fumbles for the right words, the right feelings, images and gestures. Above all, it tries, with all its might.

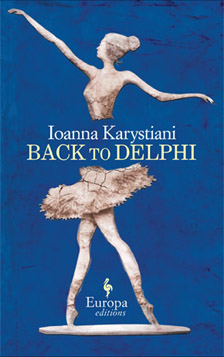

Karystiani’s voice remains thoroughly Greek, for all that she has learnt the minds of many distant men. One can hear echoes of Scarimbas’ The Divine Goat, Pentzikis’The novel of Mrs Ersi and The Dead Man and the Resurrection, Papadiamantis, Tahtsis, Karagatsis, Dido Sotiriou, and so many others. Her latest novel to appear in English, Back to Delphi, is a piece of needle-sharp realism and raw emotions. It is full of unmitigated, almost impossible gentleness, and equally sheer horror. It is eerily tangible and intensely symbolic.

It conjures up a time of extreme crisis, of total annihilation. The language has a Beckettian gait and feeling of suspense, which comes through clearly in the English translation by Konstantine Matsoukas. Back to Delphi is a novel in the tradition of the film noir: Theodore Angelopoulos is certainly in the background, as is the work of fellow director (and Karystiani’s husband) Pantelis Voulgaris. There is darkness without light, a panting slowness; inevitable, relentless eternity without a sense of ending or redemption. Without return. Also without choice? That is the central question of the novel.

One must read slowly, absorb the atmosphere of the story, allow it to seep through one’s own life and soul.”

The darkness is particularly heavy for a writer who has described the act of writing as looking through a window – she laments in an interview the loss of a small writing desk she used to have, and which she would move each time closer to a different window, according to the alternation of the seasons; so that the view would be durably beautiful and full of light. Full of colours and silent invocations. The slowness of the narrative is determined and determining, it reflects Karystiani’s own way of reading and essentially of being. One must read slowly, absorb the atmosphere of the story, allow it to seep through one’s own life and soul.

Ioanna Karystiani is appearing at Greece is the Word!, a day event on contemporary Greek literature and arts at the Southbank Centre on Saturday 19 October, and will be in conversation with David Connolly at the Ilkley Literature Festival on Sunday 20 October.

The plot of Back to Delphi is terrifyingly simple: a mother and son reunite for five days. A trip is prepared, it is offered as a brief, yet great and vital journey into hope, a second chance, an impossible pause away from the black madness of a world which weighs heavily on every utterance, every thought and every sensation. At the same time, and with hair-raising single-mindedness, it is staged as a fearful act of sacrifice. Through a whirlwind of cluttering, meandering and mundane experiences, hinting at a dark unspeakable centre, at a silent, all-devouring terror, we get a poignant sense of human devastation and tragedy. Of a dissolution without solution. Of double and lost identities.

An absent father looms far into the distance, an abusive husband, a dead man. The son grows – or rather stops growing – after the death of his father, and begins to warp and fester instead. The mother escapes, evades, gasps with desolation. He struggles to find a meaning in life. She fades away from life, in a desperate effort to still hold on, go on, even when she cannot. He ends up strangling a girl. She enters a form of non-existence by turning him in. In the five days of the novel, in a rural, Arcadian setting near Delphi, on leave of absence away from the high-security prison where the son has spent his last ten years, we are given, in chokingly concentrated form, the promise of an elixir of life – and all its most lethal poisons.

It is the simplest, starkest images which both shatter and affirm our faith in existence: in ‘The Sack’, the first section of the novel, the memory of a bucket used by the narrator’s mother since childhood to draw water from a village well, to carry garden vegetables, to hold sacred incense or simply to sit on, now becomes endearingly, menacingly, the most cherished and most personal possession. The only discordant and unifying link to past, present and future. There is a terribly strong sense of fatefulness and fate, a lyrical feeling of loss:

“For Viv Koleva the sadness of her great grandmother, her grandmother – she had heard of their fortunes, as well – and of her mother, was her female dowry. It grew with the passing years and the colourless trivia of poverty, it swelled like a river that, from time to time, dashed her progenitors onto sharp-edged banks, their lives spoken for like every woman’s of their time, though her it hadn’t washed upon some turn but dragged her on through life, until… it drew her out into the open sea, far from any shore of salvation or respite.”

One can feel that the Greek original must be a piece of intricate and transfixing craftsmanship. That the velocity and the hammering rhythms of the prose bring art and life inseparably and seamlessly together. That they release the torrents of consciousness and conscience so inextricably intertwined in the novel. Ioanna Karystiani is one of the strongest, most evocative and original writers in Greece. Her linguistic sense is organic, never contrived, for all that it is rebellious, experimental, and even on occasion disjunctive. The translation by Konstantine Matsoukas sometimes suffers from grammatical and linguistic errors, and from an uncritical use of English colloquialisms which alter the cultural identity and timbre of the text. It evinces a stylistic uncertainty and ungainliness. Yet the novel itself, its thrust and impetus, its final cathartic climax/anti-climax, easily and powerfully overcome any such difficulties.

Back to Delphi demands our attention, it offers, Karystiani tells us, “where there is no possibility of forgiveness, or promise of purification… the only true catharsis there is […]: pain, omnipotent and everlasting. Pain as seed, taking root here and there, and growing into humanity. Perhaps this is all I seek, all that I can imagine, if this is all that’s left anywhere anymore.” This very real seed of humanity is at the heart of Back to Delphi, it is the release and restoration, the oracle offered by this harrowing, gripping, powerful novel.

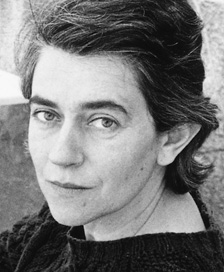

Ioanna Karystiani was born on Crete, and now lives in Athens. Her literary debut came with the collection of short stories, I kyria Kataki (Ms Kataki). Her subsequent novels The Jasmine Isle, Swell and Back to Delphi are published by Europa Editions.

Ioanna Karystiani was born on Crete, and now lives in Athens. Her literary debut came with the collection of short stories, I kyria Kataki (Ms Kataki). Her subsequent novels The Jasmine Isle, Swell and Back to Delphi are published by Europa Editions.

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London. Her latest book is her translation of Penelope Delta’s A Tale Without a Name, published by Pushkin Press.