Another Europe

by Will StoneIn the course of his long and creatively buoyant period of exile through the 1930s, Stefan Zweig expressed, in a slew of speeches and articles presented in conferences across Europe, one thing more than any other: his ardent desire to see a unification of European states, a Europe pledged to friendship, united around pluralism, freedom of thought and movement, a vigorous pan-Europeanism to offset the mounting threat of nationalism, totalitarianism and imperialism.

Despite the increasingly desperate situation during the 1930s as Nazism consolidated its grip and prospects for peace faded, Zweig kept up his utopian mantra well beyond the point of no return, for presumably no other reason than that it was in his view right and honourable to do so, advancing the humanistic argument, the only rational and dignified response in his eyes to the deranged machinations of Nazism. But Zweig was an internationally famous author, perhaps more widely read than any other in these years; his historical biographies and fine-cut gemstones of fiction were devoured the world over, and people waited on his word – the Jewish community, the top tier of European artists and writers – for it was expected of the great cosmopolitan author that forceful anti-Nazi statements would be made, denunciations of Nazi crimes, perhaps even a veiled call for a Jewish homeland. But Zweig did not deliver any of these things, visibly shrinking back from the Realpolitik of the hour; and this failure to weigh in publicly and visibly like other writers such as Thomas Mann, who made radio broadcasts denouncing the Nazis, was seen as indefensible by the majority of his contemporaries, casting a partial shadow over his exile and later colouring responses to his suicide.

Zweig abhorred politics, seeing it as the Antichrist to spiritual freedom, and thus distanced himself from it all his life. He saw a corrupt politics as having brought about the inferno of 1914 and the unstable aftermath. He firmly believed that he would do more harm than good to be sucked into a partisan position, even on Hitler. His pathological fear of his words being used for another’s ends, of his well-intentioned statement inadvertently stoking the flames, caused an impulse to recoil from any intervention, however justified. In this calculation it can logically be argued that he was wrong, for Hitler was surely a special case of extreme evil, a civilisation-destroyer who required a beyond-normal-behaviour reaction; but Zweig identified perhaps too literally with the humanist peacemakers and tolerance-preachers of the past, such as Erasmus or Castellio, and living ‘counsellors’ like the arch-pacifist Romain Rolland. This conviction to keep above the melee was further endorsed by his eleventh-hour reading of Montaigne, whom he found had pursued a similar solitary path, extricating himself from the feelers of the opposing factions and thereby, in Zweig’s eyes, retaining his inner authenticity in an earlier time of chaos and barbarism. Yet Zweig despised Hitler and the Nazis as much as anyone and harboured a special loathing for Goebbels’s insidious propaganda, which he rightly saw as the most dangerous element in Nazism’s machinery of diabolism. Even as his books were tossed on the pyres and he was obliged to break with his long-standing German publishers Insel Verlag, Zweig wore his pacifist cosmopolitanism, his right to stand apart from politics, like cerebral body armour. But this was the same man whose conscience had commanded him to express his revulsion for war, his condemnation of the madness of the time, the overreaching spirit of violence and conquest in his poetic and prophetic drama Jeremias (1917).

Much has been said about Zweig’s tendency to hang on too long in perilous situations and then make ill-starred decisions. Friderike Zweig was only too aware of her husband’s difficulty in this respect, his tendency to waver until too late. When he did make a political calculation it was often deemed naive or a blunder of sorts. In his biography European of Yesterday (1972), Donald Prater states: “Zweig’s political ideas were generally immature and ill thought out, and where he appeared to possess political insight this was often more from instinct than from clear or logical perception.” This phobia of politics and resolute ‘apolitical’ stance has its origins in the Nietzschean drive for aestheticism, which Zweig seized on, for he like Nietzsche saw the political class and materialism as the mainstays of nationalism and European spiritual decay. But it also comes from Zweig’s instinctual sense that the zone of art and literature is quite apart from anything political or social, that the inward self must stay pure. This is surely why we see him drift away from Romain Rolland’s influence only at the moment when the old man falls under the spell of Communism.

His determination to imagine Europe as a kind of spiritual engine house for the next key stage in mankind’s ascension appears now as out of time as it did then.”

This ideal may seem to us repugnant when faced with the threat of Nazism, but this is simplistic, for Zweig was looking I suspect beyond his rhetorical public statement to what uncontainable tentacles would inevitably sprout from it, and he sincerely believed for better or worse that he could do more to persuade through his works, for example Erasmus (1934). Having said all this there is also evidence which shows that Zweig at certain moments acted boldly and decisively, even ruthlessly, his sudden departure from Salzburg being the most obvious. And in all these departures and arrivals during his intercontinental exile he behaves rationally and methodically, not to mention thoughtfully, sorting out his affairs beforehand, ensuring his manuscripts and library will serve the public good, that friends and domestic staff are well taken care of. Whilst in London, a city he claimed he loved because he was largely left to himself, Zweig worked tirelessly from his Hallam Street flat for Jewish friends and the stream of exiles who appealed to him for help with visas, connections and so forth, their constant entreaties exhausting his resources of patience and time. As always with Zweig there are curious contrasts, the interplay of conscious proaction and inaction proving a labyrinthine challenge for critics and biographers.

With the advent of Hitler, Zweig was initially drawn into the radicalising potential of the National Socialists, before leaping out as it were from a burning building. Zweig thought this new movement, though evidently repulsive, might stir things up, liberate the middle classes and offset what he saw as the infection of bourgeois materialism menacing the treasured spirit of France in particular. Zweig adored France above all other nations and unsurprisingly viewed her as the natural cradle of the arts and civilised intellectual activity, the model of his civilised Europe of the spirit. He like others presumed Hitler was a transitory phenomenon, an aberration, a spark of extremism which might have beneficial side effects before being summarily extinguished. Although this delusion was short-lived, it appears to reinforce what Prater claims regarding Zweig’s slowness to realise the course of events at the beginning of momentous political change. But conversely it may also explain why Zweig corrected himself by later abandoning his Salzburg home so suddenly and thoroughly. Zweig might have been slow to see the light, but once his eyes were opened he acted without deliberation.

With the advent of Hitler, Zweig was initially drawn into the radicalising potential of the National Socialists, before leaping out as it were from a burning building. Zweig thought this new movement, though evidently repulsive, might stir things up, liberate the middle classes and offset what he saw as the infection of bourgeois materialism menacing the treasured spirit of France in particular. Zweig adored France above all other nations and unsurprisingly viewed her as the natural cradle of the arts and civilised intellectual activity, the model of his civilised Europe of the spirit. He like others presumed Hitler was a transitory phenomenon, an aberration, a spark of extremism which might have beneficial side effects before being summarily extinguished. Although this delusion was short-lived, it appears to reinforce what Prater claims regarding Zweig’s slowness to realise the course of events at the beginning of momentous political change. But conversely it may also explain why Zweig corrected himself by later abandoning his Salzburg home so suddenly and thoroughly. Zweig might have been slow to see the light, but once his eyes were opened he acted without deliberation.

Zweig’s spiritual internationalist outlook was really based on a long-developed and honed network of culturally enriching relationships across central Europe, or as Prater has it, “Zweig was quietist, seeing in internationalism not a political programme, but the sum of personal connections forged through friendship.” His vision was to extend his own model, to upgrade the most valuable element of the lost ‘golden age’ before the First World War when these friendships were formed, both to act as a foil to the pernicious and ever more unstable reality represented by totalitarianism, and to provide a design for a future European situation beyond that of the present, whose survival he severely doubted. Zweig’s inherent idealism, his overriding passion for establishing a creatively ennobling society of nations, was underwritten by periods of striking artistic achievement in the past, most notably the Renaissance. At first sight all this may appear to us today laudable, naturally desirable, yet surely grossly out of touch with the bestial realities taking place on the ground, amongst peoples cut off from Zweig’s privileged elite. His determination to imagine Europe as a kind of spiritual engine house for the next key stage in mankind’s ascension appears now, in our present age of commonplace violent extremism and materialist decadence, as out of time as it did then, at the moment when Hitler, engorged with imperial fantasies, swept his hand impatiently back and forth across the map table in Berchtesgaden. However, the sheer passion and belief, the intelligence, the evident richness of learning, the valuable sediment as it were of a lifetime’s thought and reflection Zweig conjures in support of his dream remains valid and curiously seductive. Whatever the retorts, this is no vague chimera.

***

In the pieces collected in Messages From a Lost World, Stefan Zweig strives to bring his European ideal down from the clouds and place it on terra firma; for example, in places he argues robustly for progressive education, in order to change deep-seated attitudes on race and Fatherland and encourage a new fluidity of thought, the interweaving of languages and cultures. The reader will soon see that these essays themselves interlink and one is merely reinforcing another; though the outlying theme may be different the central message remains the same. Nationalism is the sworn enemy of civilisation, whether past, present or future, its malodorous presence thwarting the development of intelligence, its tenets those of division, regression, hatred, violence and persecution. In nationalism, with the Nazis as its most lethal form, Zweig sees the agent which may finally destroy his European heartlands, finishing the job the First World War started. Zweig’s Europe is an almost mystical conviction that whatever remains of the European spirit, the sum of artistic achievement that has accrued for centuries, can only survive the modern plague of nationalism, materialism and philistinism, can only safeguard its crown jewels of philosophical thought, art and literature through a practicable spiritual integration, a higher guild of amiable coalition. What Zweig proposes is a moral defence of the European soul against the very same forces which menace our Europe now, sanity against insanity, unity against division, tolerance against intolerance, intelligence against ignorance.

Moving and haunting, inherently tragic [and] morally persuasive, these pieces show Zweig repeatedly setting out his manifesto for cultural health through fraternity in the face of fanaticism, apathy, political expediency and genocidal terror.”

But what of this spiritual unity? Is it just another word for pan-Europeanism, such as the mobile professional elites enjoy in the privileged strata of a technologically unified Europe today, or a rhetorical comfort blanket for those who see their national language and traditions dying on the world stage (notably the French, who habitually accord Zweig mythical proportions), or is there any substance to it? In these disparate pieces, culled from declarative pauses during his wanderings in exile, Zweig argues forcefully that there is. Moving and haunting, especially with the gift of hindsight, inherently tragic when planted before the brush fire of bestial realities sweeping across the continent as he wrote, yet paradoxically also morally persuasive, these pieces show Zweig repeatedly setting out his manifesto for cultural health through fraternity in the face of a Europe gradually slipping away into fanaticism, apathy, political expediency and the spectre of genocidal terror. Whether delivering a lecture in Rome or Zurich, in London or Paris, whether attending yet another conference in the ever-shrinking free-thinking world, humanistic symposiums whose influence on events he knew only too well were depressingly limited, Zweig is urgently reiterating the need for change, for action not more words. Yet in the unstable climate of imperialist muscle-flexing and virulent propaganda during the 1930s, the action required, the necessary turnaround, which he espouses so earnestly in his speeches, is held in check by the sheer physical and psychological power of the extremist forces which are already unleashed.

Since the present appears hopeless, Zweig looks to the future and the generation beyond his own, the survivors, like himself after the First World War, speaking to an audience both within and crucially beyond the present calamity. Of course that future did herald an eventual Franco-German dream collective of European nation states, and out of this techno-bureaucratic conglomeration one could argue that something of Zweig’s dream has become a reality, namely in the successful European exchange of culture, sport and the arts. But Zweig’s exultant vision of fraternity under one continental roof has hardly been realised, since nation states have in spite of the past clung on to their self-serving national powers and their nationalist arrogance with tenacity. In the extraordinary, recently discovered text ‘The Unification of Europe: A Discourse’, a speech prepared to be given in Paris in 1934 but then mothballed, Zweig puts forward the novel idea of a “capital city of Europe” whose location would change each year, giving each country a chance to be master of the greater union. Today’s policy of European Capital of Culture is something Zweig would have certainly applauded, but it is really attractive window-dressing. The sad truth is that Zweig’s noble premise of nations purged of animosity towards one another, intellectually advancing in interlingual creativity, could only happen, then as today, if the people of Europe really wanted it to happen. But through the progressive decades of the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, behind the self-congratulatory fanfares and chatter of policy-making from Brussels, nationalism lurked in one gruesome form or another, apparently muzzled on the fringes, kept at bay from the great project. Now, as fanatical Islam extends its grip and correspondingly Islamophobia rises, as the union stutters and stalls in monetary crisis, the far right is emboldened as never before, has slipped its chains, and we watch helpless as it sends out its hideous spawn. Zweig and the later constructors of the union all overlooked or optimistically sidelined a disturbing fact: that people might sign up to a collective if it does not disadvantage them, primarily in economic terms, but all the same they have the door to the motherland left ajar, ready to leap through it with the national flag whenever the time is right. The union does not replace the old enmities, the old fault lines. In their rush to renovate the European house, the decorators of the union merely laid consecutive layers of fresh wallpaper over a mouldy wall, and now those living in the house see the mould showing through again. Zweig’s grand European hothouse of the soul, a microclimate where hostility is an anachronism, did not come to pass, nor – let us be candid – did Zweig probably expect it to; but for us today, these ardent ‘lost messages’, in their endorsement of a stillborn yet still possible future, surely hold a special relevance, for they have been found, translated and made available to anglophone readers at a precarious moment for Western civilisation, as to Europe’s outer walls the outriders of atrocity are gathering.

Extracted from the introduction to Messages from a Lost World, translated by Will Stone and published by Pushkin Press.

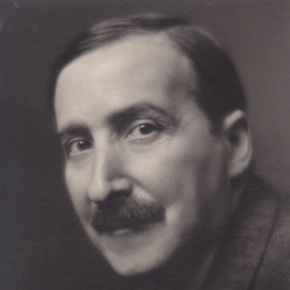

Stefan Zweig was born in 1881 in Vienna, into a wealthy Austrian-Jewish family. He studied in Berlin and Vienna and between the wars was an international bestseller with a string of hugely popular novellas including Twenty-Four Hours in the Life of a Woman, Amok and Fear. In 1934, with the rise of Nazism, he left Austria and lived in London, Bath and New York, eventually settling in Brazil. In exile he produced his celebrated novel Beware of Pity and memoir The World of Yesterday, a lament for the golden age of Europe destroyed by war. The articles and speeches in Messages from a Lost World, all appearing in English for the first time, were written in response to the ongoing destruction. On 23 February 1942 Zweig and his second wife Lotte were found dead in an apparent double suicide. Much of Zweig’s work is available from Pushkin Press. Read more.

Will Stone is a prize-winning poet, translator and essayist. His translations include work by Roth, Rilke, Traki and Verhaeren, and he contributes reviews and essays for the TLS, The London Magazine and Poetry Review. His translation of Zweig’s Montaigne is also published by Pushkin Press.

Will Stone is a prize-winning poet, translator and essayist. His translations include work by Roth, Rilke, Traki and Verhaeren, and he contributes reviews and essays for the TLS, The London Magazine and Poetry Review. His translation of Zweig’s Montaigne is also published by Pushkin Press.

willstonepoet.wordpress.com