A fortunate tyranny

by François-René de Chateaubriand

Statue of Napoleon in the Place Vendôme, Paris by Augustin-Alexandre Dumont, 1875. Siren-Com/Wikimedia Commons

A monstrous pride and an incessant affectation spoil Napoleon’s character. At the time of his supremacy, what need had he to exaggerate his stature?

He took after his Italian ancestors: his nature was complex: great men, a very small family on earth, can unfortunately find no one but themselves to imitate them. At once a model and a copy, a real person and an actor playing that person, Napoleon was his own mime; he would not have believed himself a hero if he had not dressed himself up in a hero’s costume.

Napoleon’s qualities are greatly adulterated in the gazettes, the pamphlets, the poems, and even the popular songs impregnated with imperialism. All the touching things attributed to Bonaparte in the ana about the ‘prisoners’, ‘the dead’, and the ‘troops’ are fabrications to which the actions of his life give the lie.

Bonaparte had nothing good-natured about him. Tyranny personified, he was hard and cold: that coldness formed an antidote to his fiery imagination; he found in himself no word, he found only a deed, and a deed ready to grow angry at the slightest display of independence: a gnat that flew without his permission was a rebellious insect to his mind.

Daily experience shows that the French are instinctively attracted by power; they have no love for liberty; equality alone is their idol.”

It was not enough to lie to the ears; it was necessary to lie to the eyes as well. Here, in an engraving, we see Bonaparte taking his hat off to the Austrian wounded; there, we have a little soldier boy preventing the Emperor from passing; farther on, Napoleon touches the plague-stricken people of Jaffa, or he crosses the St Bernard Pass on a high-spirited horse in driving snow, when in fact the weather was as fine as it could be.

Are not people now trying to transform the Emperor into a Roman of the early days of the Aventine, into a missionary of liberty, into a citizen who instituted slavery only out of love of the opposite virtue?

Daily experience shows that the French are instinctively attracted by power; they have no love for liberty; equality alone is their idol. Mounting the throne, Napoleon seated the common people beside him; a proletarian king, he levelled the ranks of society, not by lowering but by raising them: levelling down would have pleased plebeian envy more; levelling up was more flattering to its pride. French vanity was puffed up too by the superiority which Bonaparte gave us over the rest of Europe; another cause of Bonaparte’s popularity was the suffering of his last days. After his death, as people became better acquainted with what he had endured at St Helena, they were moved to pity; they forgot his tyranny. We were reminded of his fame by his misfortune; his glory has profited by his adversity.

Finally, his wonderful feats of arms have fascinated the young and taught us all to worship his brute force. His incredible good fortune has left to the conceit of every man of ambition the hope of reaching the point which he attained.

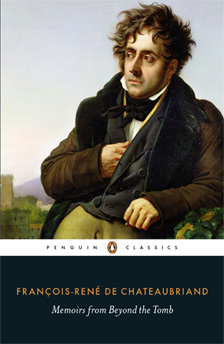

This is an edited extract from Memoirs from Beyond the Tomb, translated by Robert Baldick, published in a new edition by Penguin Classics with an introduction by Philip Mansel.

François-René, Vicomte de Chateaubriand (1768–1848) was a reactionary against the ideals of the French Revolution and the most celebrated figure in French literature during the First Empire. As a soldier, writer and politician, his days were divided between war and peace, wealth and penury, joy and despair. Memoirs from Beyond the Tomb captures his exotic adventures, heroic battles, political struggles, passionate beliefs and frequent bouts of loneliness, and is filled with sharp wit, awe of nature, and a restless desire to understand and explain the fleeting human spirit.