A fresh start

by Cristina Fernández CubasShe had decided to make a fresh start. She had to make a fresh start. And as soon as she arrived at the small apartment-hotel, chosen at random and booked in Barcelona through a travel agent, she thought it was the ideal place to allow her to stop wondering “How do I go about it?”, “Where do I begin?”, “What’s the recipe for starting a new life?” The room was large and bright. There was a kitchenette, a big bed and the bathroom had everything she needed. There was a sofa, armchairs, a dressing-table attached to the wall and a large window looking out on to Gran Vía. The fact that there hadn’t been a single room available for these particular dates at her usual hotel in the Paseo del Prado, the one she always went to, had been a stroke of luck. The same thing had happened with all the other alternatives she resorted to whenever her usual hotel told her on the telephone, “I’m very sorry. We’re full up.” Something had to be going on in Madrid during those first few days of spring – a particularly important conference, trade fair or symposium. Now she was glued to the window, protecting her eyes from the sun behind dark glasses and watching the activity in the street, fascinated. It was as if she were watching a silent film with a huge budget. There were thousands of extras, all the colours of the rainbow and lots of action. Some of the actors were trying to attract more attention and play a bigger role. She had seen one stylish passer-by cross the road at least four or five times. Where on earth was that man going – if indeed he was going anywhere? She moved away from the window and opened her suitcase. Two nights. She would be there only for two nights. But perhaps she would stay longer another time, for a week or a month. She turned on the television and put on the music channel. Then she switched on the air conditioning. For a minute she thought this really was her usual hotel and felt a hankering for what she had lost a long time ago – the urge to read, write, turn the dressing-table into a writing-desk, cook, stock up the fridge, go to the theatre and the cinema. More than anything, she wanted to come back. She wanted to come back to that bright room every evening, and, given the choice, she wouldn’t change a thing. It was hers. She had been given a room that belonged to her.

Eight months had already passed since he had gone. Eight months that time hadn’t measured in the usual way. Sometimes they seemed like an eternity, sometimes they seemed like smoke-rings jauntily colliding in the air.”

She looked at the key. Room 404. She had liked the number straight away. Four plus four equals eight. The symbol for infinity, she remembered, is a figure 8 on its side. An isolated zero, she thought, in principle has no value. It’s nothing. Or perhaps it is something. Perhaps it’s not a number but actually a letter. An O for oxygen, for example. She took a deep breath and turned off the television, the music channel and the air conditioning. Then her mind went back to the figure 8, to the key she was still holding in her hand. Four plus four equals eight. Eight months had already passed since he had gone. Eight months that time hadn’t measured in the usual way. Sometimes those eight months seemed like an eternity, just like the figure 8 on its side. And sometimes they simply seemed like smoke-rings jauntily colliding in the air between puffs on a cigarette. That’s what her eight months had been like – interminable and empty.

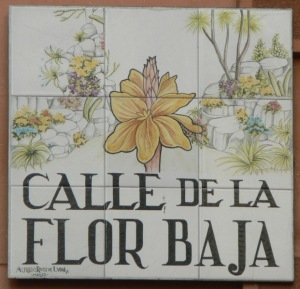

She went out, and now she was part of the film, too. She was one more extra, one among many thousands. Perhaps at that very moment someone from a double-glazed window, from a soundproofed room in some hotel, was watching her among the crowd. She liked the thought that whoever was watching her – whether it was a man or a woman – would suddenly feel strangely relaxed and happy, just like she did now. She walked down Gran Vía and thought how lucky she was – the room, such a beautiful day, wanting to get down to work again, to start living again. She had barely walked a block when she stopped in a square. She was surprised that what she thought was a square actually had a street name, calle de la Flor Baja. But that morning wasn’t like any other. She’d decided that it wouldn’t be like any other. She sat down at a table outside a bar, opened her diary and wrote “Flor Baja”.

She ordered a beer. She was sure she would never go back to the old hotel in Paseo del Prado. Flor Baja could very well be the starting point for a new itinerary. She would have new interests, start new habits, and perhaps her new life was beginning just at that very moment. She looked through her diary. She had arranged to have dinner with a friend that evening and had to go to an office to sort out some paperwork the next day. Suddenly the very idea of the dinner felt like torture, and it seemed as if the paperwork had just been a pretext to spend a few days in Madrid and have a change of atmosphere. She wrote down, “Cancel dinner and send documents by post.” She looked at the things she had written down on previous days. There were sayings, suggestions, reminders to be optimistic and how to behave. She smiled as she noticed that in a fit of fury she had ended up striking them all out for being useless. Only two of them had escaped the carnage: “Live for the day” and Einstein’s words of condolence to a friend’s widow, “Your husband has departed this world a little ahead of me, but you know that for me, as a physicist, neither the present nor the past exist.” She couldn’t remember the friend’s name or his wife’s, but she did remember how many times she had read those words in amazement, as if they were meant exclusively for her. The past, the present… of course the past existed. The only problem lay in what exactly the past was. Sometimes it insisted on disguising itself as the present. Voices, laughter, whole sentences often made her turn around hopefully in a cinema or in the middle of the street. Just as they would make her toss and turn anxiously when waking up from a dream. But now… she called the waiter over and quickly paid for the beer and didn’t wait for the change. What was happening now?

Perhaps in her new life she would do nothing more than follow any stranger who looked like him. She had no time to feel sorry for herself, to turn around or even to realize that she was behaving like a madwoman.”

She had just seen him. Him. The man who had left this world almost eight months earlier. The man with whom she had shared her whole life. He was wearing an old beige jacket. That beige corduroy jacket! He was absent-mindedly crossing the square in the middle of the calle de la Flor Baja. She followed him cautiously. She was right. Although the similarity was remarkable, she knew it could only be an illusion. But that morning, she’d decided, wasn’t like any other. She’d felt that immediately, as soon as she’d walked into room 404 and felt it was hers. It was a morning unlike any other, and he was now walking down Gran Vía, and she was following in his footsteps like a shadow at a sensible distance. A few seconds later he stopped at a newsstand. She saw him hand over a few coins and pick up a packet of cigarettes, and then he moved off again. No, she said to herself, that’s not possible. He gave up smoking years ago. Although “neither the present nor the past exist”, she remembered, and it was only then that she thought she understood the reason she’d once written down that sentence to which she repeatedly returned. Perhaps in her new life she would do nothing more than follow any stranger who looked like him. She had no time to feel sorry for herself, to turn around or even to realize that she was behaving like a madwoman. He, whoever he was, had suddenly turned around as if her eyes were burning into the back of his head, and she had no option but to hide in a doorway. She was quick. He didn’t see her. But the look on the doorman’s face made her realize that she was acting ridiculously. Or was she? She told herself that she wasn’t. What was wrong with following someone you love? The man who, defying all the laws of the universe, had reappeared in Madrid in the full light of day one sunny morning delightfully confounding his own past.

She walked into the street again and for the second time in a few minutes felt as if she were taking part in a film, but now she wasn’t just another extra, someone to make up the numbers. She was walking surprisingly nimbly, and she had an objective: not to lose sight of the old jacket; to follow it at a distance. And for a few moments she thought that the people walking around and about her realized what she was doing and were aware of her objective. That was why they were looking at her, falling into step with her, spurring her on. But were they really spurring her on? She wasn’t young any more and had passed through the doors of invisibility some time ago. She could move around comfortably without anyone paying her any attention. And now, when she needed to be more anonymous and invisible than ever, she was the target of comments, remarks, flirtatious compliments, outrageous proposals. What was happening that morning on Gran Vía? Before she had time to answer her own question he suddenly headed off, taking great strides, and she had to run to keep up with him. She no longer cared that people were looking at her or that some idiot jokingly tried to block her way. She couldn’t lose him. Those great strides of his – that was how he walked, with great strides. Then he stopped dead in his tracks. He often used to do that. When he remembered something important he would stop dead in his tracks. She took a deep breath and stopped in front of a perfume shop. Just for a few seconds, she thought, until he moves off again and I can follow him without being noticed. But the glass in a mirror reflected her face back at her, and she just stood there fascinated, astonished and not moving a muscle.

Because it really was her. Who could say how many years ago, but it was her. She was wearing a very short skirt, and her long, shiny chestnut hair was loose. She thought she looked pretty. Very pretty. Had she ever been so pretty? She wanted to think she was in a dream, someone else’s dream. Wherever the man she loved was, he was dreaming about her, and now she was looking at herself through his eyes. That’s how he must have seen her around the time they met; that time, so long ago now, when anything seemed possible. She took a great big breath and had the feeling she had already experienced that moment. The shop window, the mirror, her girlish reflection, Gran Vía one sunny morning. A mirage or simply an optical illusion. The sun, her reflection, a trick of the mirror, the objects and posters in the window becoming entwined with her own image.

“Where did you get to?” she suddenly heard.

She put her hand out to stop herself from falling over. He was there – tall, slim and just as young as when they first knew each other. There was no longer any doubt. The boy in the beige jacket was right there, behind her, and he’d just put his hand on her shoulder.

“Come on. We’re late. Don’t forget, we’re meeting up with Tete.”

He put his arm around her waist, and she let herself be led away like an automaton. Tete Poch. Tete Poch had died years before. Tete was the first of their friends to disappear, to abandon this world. But now it seemed as if none of this could have happened yet. Tete was still alive. He had not yet departed to the place from which there is no return, and she was a girl with long hair who wore amazingly short skirts. She took a deep breath, and once again thought she might faint. She bit her lip until it bled. It wasn’t a dream. This was really happening. She gradually recognized streets, shops and bars. They went into one that seemed surprisingly familiar. She knew the place. There was a time she used to go there regularly, although she couldn’t now remember its name. A blotchy mirror reflected back her face. She was still pretty. And there he was beside her, very, very young, wearing that nice corduroy jacket he never wanted to take off and which she still (without knowing why) kept in the wardrobe.

“Tete’s borrowed a car off someone. We could go to Segovia for the day.”

“Great.”

“What’s up? You’ve hardly said a thing all morning.”

She shook her head.

“You were walking so quickly…”

Tete hadn’t arrived yet. It was better that way. She needed some time to take in what was happening. He had just taken out a book from his pocket.

“I found it in an old bookshop yesterday. It’s a real gem.”

She looked at the cover. The Oresteia by Aeschylus. She was surprised that she could read the title without her glasses. Her sight was still good back then. Perhaps, but anyway she’d recognized the book immediately. It was still at home, too, on the bookshelf in the study. She hadn’t dared take anything out of that room, even though he had gone.

“It’s a trilingual edition,” he said proudly. ‘Classical Greek, Modern Greek and English.”

“Yes.”

He took her hand. “Something’s up with you. Or are you worried about the exam?”

The exam? What exam?

“I’m sure you’ve passed. Don’t worry.”

She suddenly began remembering: Tete, a beaten-up old car, the three of them in Segovia, the journalism exam. That’s why they’d gone to Madrid. She had to take an exam in journalism, and he’d gone with her. They went everywhere together, almost from the first time they’d met at the Faculty of Law in Barcelona. They were never boyfriend and girlfriend. They didn’t like those words. They hated them. They were friends. That’s what they used to say. ‘FRIENDS’ in capital letters. No one had been surprised that some years later the friendship turned into marriage, although they didn’t like the word ‘marriage’ either and ‘husband’ and ‘wife’ even less. They thought they sounded formal and boring. If anyone had asked them what they were back then, at the time Tete was around and when they used to go to Madrid and when she was taking the journalism exam, they would have said ‘FRIENDS’.

“I’m just going to the toilet,” she said, and he stroked her cheek. Her cheek, my God, her cheek was burning! She was scared she would burst into tears, get emotional, say something out of place and spoil the marvellous encounter. She got up and added, “I’ll be back in a minute.”

She didn’t need to ask where the toilets were or stop to look at the sign (‘TOILETS. TELEPHONE’) because she knew exactly where she was. It was as if she had been there just the day before. She went down a couple of steps and turned back to look at the table. Tete had just arrived, and they were giving each other a hug. They were giving each other a hug! Then she did burst into tears. Tears of joy, tears of forgotten joy. Her mascara had run into one eye, and she almost had to feel her way down to the toilets. She splashed some water on her face when she got there. She needed to clear her head and sort herself out. She had to look happy and carefree and think there was still a whole life ahead of them. If they were surprised at how she looked or guessed that she’d been crying, she would simply say, “Bloody mascara. I don’t know why I bother with make-up.” She suddenly remembered that that was exactly what had happened. She remembered it clearly, word for word. “Bloody mascara. I don’t know why I bother with make-up.” She also clearly remembered that, on that morning she’d miraculously been allowed to relive, her eyes had stung for a long time and they went to a chemist’s and bought eye-drops (which brand was it?). Then they all got into the borrowed car and sang songs the whole way. Back then it was quite a journey to get to Segovia. They sang war songs, anthems, banned lyrics that were just as forbidden as the fact that she, a girl of twenty years of age at the time, should be in a car with Tete and him, as free as birds, happy and carefree, while her parents in Barcelona thought she was taking an exam or studying. What a charmed life they’d led before mobile phones. She dried her face with a towel (paper towels still hadn’t invaded the toilets) and went up the steps two at a time. She was ready. She knew the script and was happy. She was the happiest girl in the world, even though her mascara was still running and for a moment, when she rubbed her eyes, she could see only a grey mist. Bloody mascara!

***

For a second she thought she’d made a mistake and that the bar had another room or that the toilets were shared between two different premises. But there was only one staircase and upstairs was a soulless bar with an enormous counter, a few customers and a dozen tables piled up any old how in a corner. “Where are the young men who were here a short while ago?” she asked a waiter in a quavering voice. The man shrugged and didn’t understand. She leaned against the wall. Where had they gone? How could they leave her behind?

A young woman offered her a seat and asked, “Are you OK?”

She shook her head.

“She seems confused,” said the waiter. “She came in a while ago and went straight to the toilets.”

The young woman spoke to her gently, very slowly and in a loud voice as if she were a foreigner who found it difficult to understand. “What’s your address? Shall we call a taxi for you?”

She didn’t reply. She opened her handbag and took out a small mirror and looked at herself in it for a moment. She wasn’t surprised. In the distance she could hear a hum of voices wondering what was going on and the young woman asking for a napkin with some ice-cubes and talking to the onlookers.

“It’s all right. The lady doesn’t feel very well.”

She went back to the hotel, to the apartment-room she had liked so much that morning. The past, the present, she remembered. There is no past and there is no present. Today, the present had slipped into her past. Or it was the other way around and fragments of her past had surfaced in the present? She opened her suitcase. By this time they would already be on the way to Segovia. Once more she wondered how they could have left her behind. But taking the high-speed train would mean she could overtake them and get there before they did. The present racing against the past. Not everything was lost yet because once again she remembered everything perfectly well: the restaurant, as much wine as you could drink, searching out a cheap hotel for the night. The names and the exact locations didn’t matter. She would go to each and every restaurant, inn, tavern or hostelry until she found them. It would be best to leave her suitcase down at reception and travel without any luggage. There wasn’t a second to lose. She would take a taxi and go to Chamartín Station. She’d catch up with them and would reappear in that delightful day from so long ago. Tete, him and her, with their whole lives ahead of them.

She was grateful for the miracle of time travel, the hope that if that (whatever it was) had happened it could happen again.”

The key slipped out of her hand and clattered on the floor. She saw the number on the key fob and smiled. She smiled. “Eight months, oxygen, four plus four, infinity.” She kneeled down, picked up the key and couldn’t help recalling her thoughts from just a short while ago, her frustration or despair at her question “How could they leave me behind?” But also, as she was leaning against the bed to help herself get up, she was grateful for the miracle of time travel, the hope that if that (whatever it was) had happened it could happen again; clinging to Einstein’s words, which had become a mantra: “There is no past and there is no present.” Suddenly she understood that she’d made a mistake about something very important. They hadn’t left her behind. How could she have thought something so ridiculous? Of course they hadn’t left her behind. There they were, the three of them, together on the road in an old banger someone had lent them, singing and laughing. They were free! That day from years and years back she had experienced once again just for a few moments was not over. She squeezed the key as if it were an amulet. 404. Oxygen. Four plus four equals eight. Infinity was a figure 8 on its side. She opened her hand without realizing it; the key slipped from it once more and hit the floor. But now she thought it was mocking her. A fresh start. A fresh start. A fresh start.

She sat down at the dressing-table and looked at herself in the mirror. She wouldn’t go anywhere. The past had a cast-iron script, and there could be no improvisation. Whatever Einstein said, the past and the present were two irreconcilable spaces. She had been on the verge of doing something crazy; the whole morning had been completely ridiculous. If she closed her eyes she could still see and hear them – the songs, the car and the road – but if she opened her eyes she saw her tired old face again. That’s what her new life was offering her. It would be no use to try to cheat the clock and steal back times that didn’t belong to her any more. For a moment she saw herself, exhausted and in a sweat, finally finding the bar where the three friends were cheerfully chatting and discreetly sitting down at a nearby table to watch them and to wait for the miracle to work its magic once again. But now she felt ridiculous. She felt like an intruder, an interloper, a gooseberry, because those three were twenty years old; they were young and living for the moment. And, what was now clearer than ever, they didn’t need her for anything. They didn’t need a sixty-year-old woman staring into a mirror who sometimes, occasionally, didn’t feel very well.

From the collection Nona’s Room, translated by Kathryn Phillips-Myles and Simon Deefholts

Cristina Fernández Cubas is a writer and journalist who lives and works in Barcelona. Since the publication of her first collection of short stories, Mi hermana Elba in 1980, she has stood out as a master of the form. She received the Setenil prize for short stories for her fifth collection, Parientes pobres del diablo in 2006. She has also published several short novels. Many of her works have been translated into Dutch, French, German, Italian, Norwegian, Portuguese, Turkish and Chinese. Nona’s Room is published by Peter Owen Publishers in their World Series Spanish Season. Read more.

Cristina Fernández Cubas is a writer and journalist who lives and works in Barcelona. Since the publication of her first collection of short stories, Mi hermana Elba in 1980, she has stood out as a master of the form. She received the Setenil prize for short stories for her fifth collection, Parientes pobres del diablo in 2006. She has also published several short novels. Many of her works have been translated into Dutch, French, German, Italian, Norwegian, Portuguese, Turkish and Chinese. Nona’s Room is published by Peter Owen Publishers in their World Series Spanish Season. Read more.

Author portrait © Pilar Aymerich

Kathryn Phillips-Myles and Simon Deefholts have jointly translated a number of plays for the Spanish Theatre Festival of London, and two other books in the 2017 Peter Owen World Series Spanish Season, the novels Wolf Moon by Julio Llamazares and Inventing Love by José Ovejero. Read more.