The eye of the Gorgon

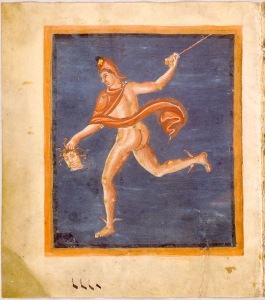

by Mika Provata-Carlone The middle of August, and by extension the end of summer, is the time of the Perseids – magnificent, prolific meteor showers, majestic shooting stars inspiring us with awe at this glimpse of eternity and immensity, but also forcing us to shudder at the prospect of chaos and human mortality. They herald divine illumination and cosmic catharsis, and invoke, thanks to their name, man’s potential to defeat absolute evil: Perseus, who founded the house of the Perseids, and after whose constellation the meteor showers are named, killed the Gorgon Medusa – a mere human hero triumphing over unspeakable, monstrous horror. Yet within that triumphant human moment lurks also darkness, the Eye of Medusa is the brightest star of the constellation, reminding us that wishes upon shooting stars often turn awry – and that magic lanterns, whether room-bound or floating in lilting processions across the summer night sky, can burn cruelly and absolutely, can project as much illusion as charmed images.

The middle of August, and by extension the end of summer, is the time of the Perseids – magnificent, prolific meteor showers, majestic shooting stars inspiring us with awe at this glimpse of eternity and immensity, but also forcing us to shudder at the prospect of chaos and human mortality. They herald divine illumination and cosmic catharsis, and invoke, thanks to their name, man’s potential to defeat absolute evil: Perseus, who founded the house of the Perseids, and after whose constellation the meteor showers are named, killed the Gorgon Medusa – a mere human hero triumphing over unspeakable, monstrous horror. Yet within that triumphant human moment lurks also darkness, the Eye of Medusa is the brightest star of the constellation, reminding us that wishes upon shooting stars often turn awry – and that magic lanterns, whether room-bound or floating in lilting processions across the summer night sky, can burn cruelly and absolutely, can project as much illusion as charmed images.

Shooting stars and magic lanterns are the powerful symbols in Stefan Zweig’s Shooting Stars: Ten Historical Miniatures and Rachel Polonsky’s Molotov’s Magic Lantern, which seem to be seeking no less than a redefinition of history as they each embark on a timeless journey into the human condition.

Both Zweig and Polonsky are storytelling historians – they wish to engage not only our intellect, our critical faculties, but, vitally, they wish to capture our humanity.”

In Molotov’s Magic Lantern, Polonsky invites us to share a kaleidoscopic and delicately crystalline perspective into Russia past and present. Published in 2010, and receiving in May this year the prestigious Città delle Rose international prize for essay writing, this is more than a survey or a philosophical peregrination through time and space. Polonsky, finding herself in Moscow researching Russian Orientalism, decides to transcend the prescriptions of academic papers and explore her subject as a living, breathing experience, infused with all that a very rich and rigorous scholarship has taught her, and motivated by what Nikolai Fyodorov believed to be the true aim of all human inquiry: “to study means not to reproach and not to praise, but to restore life”. Polonsky seeks to restore this Russian life that has captured her mind and imagination, and her gift is to be able to offer stirring critical insight through an almost haunting prism of grief, an unflinching, yet equanimous witnessing of horror, alongside what she sees as the beauty of the Russian landscape, of the much-sung Russian soul.

Polonsky transports us with this sense of secular eternity that seems to emanate from the country’s greatest authors, painters, musicians, simple peasants and great sages. We learn insatiably, relish luxuriously all that she has carefully and exquisitely collected for our sake. Her journey is gentle, with a note of yearning, as she seeks long-lost treasures and old, resonant, vital voices. She writes so that we may see with her, feel as she does, and above all think about what was there and is now perhaps catastrophically lost.

Polonsky’s pilgrimage into the Russian past, more distant or startlingly close, bears witness to her sharp, inexhaustible erudition, her rare talent for words, for a narrative that is as light and engaging as it is riveting in the breadth and wealth of its individual elements. Her love for the human detail behind all that contains the greatest meaning (or the deepest trauma and most harrowing pain) is what makes this book a unique chronicle as well as a fundamental essay on Russian history – on history as a discipline, as a human enterprise, as a way of experiencing both the singular and the universal.

For Polonsky, history cannot be only evidence, facts, events and historical landmarks. Nor can it be reduced to annals, stories, personal accounts. History has to be ruthlessly honest and pragmatic, as much as it has to be intimate, introspective, private, a comparative study of nodes, connections, encounters, actualised or failed. It has to be diachronic and synchronic at the same time, in order to encompass as much of human experience as possible, urge the human spirit to look through that chink in the wall of Goethe’s “mysterious workshop of God” (and, more tragically, of man). “History does not move forward. It moves not in a line, nor a circle, but in an arabesque, which is not always a line of beauty,” writes Polonsky, and the arabesque in Molotov’s Magic Lantern has a soviet curve and goring angularity.

Her achievement is to present us with a razor-sharp analysis of the Soviet era, ideology, systemic governance and the feel and pulse of everyday life, without ever dismissing the human substance – no matter how much that may have been quashed, transmogrified, betrayed. She listens quietly to the voices of the dead and is determined to break the silence of killers. That “powerful force: the life of past epochs”, “everything known and remembered”, becomes in Polonsky’s book a plea for a present that will reclaim the duty of remembrance, that will restore meaning where harsh forms and shapes have taken root. Her history of Russia is as much an elegy as it is a lament – a poignant declaration of love, as much as it is a scholar’s testament of truth.

Truth and memory, futility and promise, human genius and catastrophe, are the themes of Stefan Zweig’s Shooting Stars. In this new translation by Anthea Bell, Zweig’s ‘miniatures’ number ten in all, instead of the original fourteen in German (and also in the Italian and Spanish editions) or the odd twelve of the Arabic and French translations. We will not read about Goethe’s unfulfilled love for Ulrike von Levertzow, of Dostoyevsky pardoning his planned execution, about Leo Tolstoy’s death or Cicero’s plea for the restoration of the Republic after Caesar’s assassination. Humanity has also lost the fight to history in the English title: Zweig’s original was Sternstunde der Menschlichkeit – stellar hours of humanity. Yet the image of the shooting star coveys supremely the sense of tragic grief and despair which, as in Polonsky’s book, determines the tone of this collection of “variations on a theme” – namely the theme of human fatality or, perhaps more honestly, human inadequacy in the face of historical schemes that contain more than their fair share of human stupidity and guilt.

It also suggests a different force at play: Zweig is not tranquil in his gaze, does not, and will tragically never have, the critical distance from his own momentous historical hour, which he will choose not to survive, but from within which he vitally writes, shoots, every word of these tensely compact, superbly distilled vignettes. Like his hero in Journey Into the Past, Zweig “listen[s] yet more intently to what was within him, to the past, to see whether that voice of memory truly foretelling the future would not speak to him again, revealing the present to him as well as the past.” By revisiting known or unknown defining moments in the lives of people and nations (the complete miniatures generously span the years between 1453 and 1919), Zweig explores no less than Herodotus’s fundamental premise regarding history: “the worst pain a man can suffer is to have insight into much and power over nothing.” This is an impetuous discourse that unites philosophy to angst, history to anecdote, eternity to the burning present moment: we learn about Scott’s final hours, El Dorado and the man behind it, Waterloo and the making of one man’s fortune, Columbus’s “sublime folly”, about wires across the Atlantic Ocean, Handel’s moment of divine inspiration and the writing of ‘La Marseillaise’; about how “in history, as in human life, regret can never restore a lost moment and 1,000 years will not buy back what was lost in a single hour” as in his sketches of the fall of Constantinople, Lenin’s return to Russia and Wilson’s shattered dream of peace.

Zweig’s recurring question throughout his writings concerns people, historical or fictional, who get things wrong, who are “making the wrong diagnoses” as he says in Beware of Pity. Significant or insignificant individuals who fail in their estimation of circumstances, history, humanity, who misconstrue and misuse what they blindly identify as power and opportunity. In parallel ways, Zweig and Polonsky seek to understand not only human fatality or futility, but most particularly men who branded history with their passage, action or inaction, who were “both devout and cruel, passionate and malicious, scholar[s] and lover[s] of art, who read Caesar and the biographies of the Ancient Romans in Latin and at the same time [were] barbarian[s] who shed blood as freely as water” as Zweig writes of Mehmed II. The cultured monster and the faceless unique individual are their central theme, as well as “unforgettable ecstasies of downfall” such as perplexing personal libraries acquired through the extermination of both friends and capriciously defined foes, the last mass in Saint Sophia or El Dorado – that incredible, fantastical and all too real historical parable to world markets and economy, international law and a single, fragile man – what Zweig calls the elemental.

Both Zweig and Polonsky are storytelling historians – they wish to engage not only our intellect, our critical faculties, but, vitally, they wish to capture our humanity. Their ‘stories’ are systematically and critically collected, checked against evidence and sources, turned into poignant historiographical narratives. Like Herodotus, they urge us to examine civilisations in conflict – a hubristic humanity in crisis. They seek the reasons behind history’s failure, point out monumental acts and hours of stupidity, cruelty, common indifference, discomfortingly complacent fatalism and ludicrous, criminally misjudged instants of heroism. They offer us Bildungsromane of humanity’s tragic self-illusion, of the brittleness as well as the titanic force of history, of the vital necessity to hope beyond what is either possible or probable. They both present us with different, exquisite analyses of the sorrow of progress, present and timeless, and they invite us to think about what distinguishes creative chaos from destructive mayhem. They do so with childlike enchantment – the unshakeable faith in the possibility of listening, understanding, sharing, combined with an old sage’s lament.

To use Kant’s term, these are extraordinary feats of the art of being crucially “purposeful without a purpose”; they are free of any insular central theme, possessing instead a harmony of multifarious strains, the voices of lost souls and living ghosts.

c. 830–840. Leiden University Library/Wikimedia Commons” width=”160″ height=”181″>Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.

c. 830–840. Leiden University Library/Wikimedia Commons” width=”160″ height=”181″>Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.

Rachel Polonsky’s Molotov’s Magic Lantern is published by Faber & Faber, and Stefan Zweig’s Shooting Stars: Ten Historical Miniatures by Pushkin Press.