Hailstorm

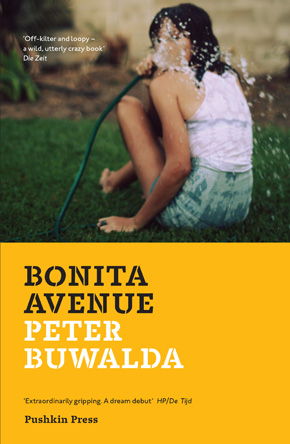

by Peter BuwaldaSiem Sigerius is a maths professor who delights in putting his students straight about coincidence theory. When he sees an image that might depict his adopted daughter on an erotic website, he has to weigh up the probability that she and her photographer boyfriend have started a sideline in porn…

The tepid downpour shades the Shanghai twilight. Gurgling, the rainwater seeks out drains and sewers, sloshing against the Hauihai Zhong Lu sidewalks, over which hundreds of Chinese tread hurriedly with precise steps, shielding their straight hair with umbrellas or briefcases. Occupied taxis spray fans of glistening water; shoppers, their arms ending in clusters of purchases, take cover under awnings or in doorways, staring into space or conversing in their secret language. The usually thriving, vibrant, pulsating avenue with its high-priced shops, malls, hotels and restaurants almost looks covered, it is so dark.

Jaywalking against a red light, he crosses a flooded intersection, dodging the aggressively advancing taxis and rickshaws. His suit jacket is drenched, lukewarm rainwater soaks the toes of his shoes. He takes large strides, a curious disquiet steers him towards his hotel. On the one hand he believes his suspicions say more about himself than about Joni, that what he has seen is a projection of his own fears; but on the other hand he is just a bit too familiar with adversity to be entirely sure. As different as his daughters are, he has never doubted their respectability, their decency: it is a question a man with a son in the Scheveningen penitentiary never gets around to asking. He would put his life on the line for Tineke’s daughters, Janis and Joni, whom he regards as his own – the elder, who has everything going for her, who will breeze through life: she is quick on the draw, witty, ambitious, above all engaging – “take the plunge with me”, it’s written on her forehead in glittering gold letters – and on top of it those damned good looks, her extraordinary beauty, so no, the father of a criminal does not worry about a daughter like Joni. If there is any of Tineke’s brood to worry about it is Janis, who is altogether another matter. The younger daughter has made it her life’s work not to engage, she harbours a programmatic, often intolerable, loathing for everything that in her eyes is not genuine, she fights a one-woman guerrilla against everything that is insincere, fake, hypocritical. That is why she refuses to diet, that is why she wears boys’ clothes, that is why she so vehemently abhors money, meat-eaters, Hollywood films, saddled horses, universities, vacations. She shreds Christmas cards sent by aunts and uncles. Deodorant: Tineke had to force her to use deodorant, as a teenager Janis insisted it was a lie to mask your own odour, it’s deceitful, deodorant is bourgeois. At least she’s honest, he and Tineke told each other.

The heavens open, downpour turns into hailstorm, the deafening drumroll is so loud that the traffic appears to glide noiselessly forwards. Sigerius has no choice but to take refuge under a sodden awning. Packed together with other pedestrians, he picks up a scent that reminds him of the sweaty judo mats of long ago. One of the men points to the bouncing ice balls, maybe he’s never seen hail before, at least not on 13th May.

For a couple of years he was the jogging coach for Joni’s gymnastics class; after returning from America she joined a club in Enschede called Sportlust, and one day she asked if he felt like coaching them. Sounds good, he said, and it did sound good: a weekly run with thirteen thirteen-year-olds through the Drienerlo woods. Shortly before his summer holidays, the chairwoman and the head coach sat in his living room discussing the details; soon thereafter, every Wednesday evening the farmhouse overflowed with beanpoles with braces and tracksuits, a party that Joni soon regretted because all the girls cancelled now and again – homework, illness, being under the weather – something she could never get away with. He laid out a not-too-girlish route of about four kilometres. They ran southwards down the Langenkampweg, cut across the campus, including the motorcycle club’s dune (“Oh, noooo, sir, not the loose sand!”), after which they continued through the woods until coming out at the farmhouse, where Tineke served them glasses of elderberry cordial.

Joni was still young enough to be proud of her athletic father, and he too would have looked back with pleasure on the training if it hadn’t been for that incident. Sportlust participated, as it did each year, in a door-to-door fund-raising drive for cancer research, and Joni and Miriam, a small but pert girl who jogged with her blonde curls flattened under a headband, spent two long afternoons canvassing the houses and apartments in Boddenkamp for donations. “A neighbourhood where you can expect them to be generous, just like in previous years,” remarked the chairwoman the evening he phoned her because Joni had come home from try-outs and – first stammering, then crying – told him she’d been accused of stealing money out of the collection can.

While counting the takings, the woman told him, the Sportlust treasurer noticed that Miriam’s and Joni’s cans didn’t contain a single banknote, and that their proceeds were not only less than a quarter of the previous years’ but the lowest of all the other cans, even the ones from what she called the grotty neighbourhoods. Miriam was in the Tuesday evening gymnastics group; they took her aside and within ten seconds she had confessed. According to her, she and Joni managed to fish out all the paper money with a geometry triangle and then divided the loot – a little over 150 guilders – between them.

Joni was furious. What a bunch of lies. She had nothing to do with it! How could somebody be so mean. She hated that Miriam, she always knew she had a mean streak, she should never have trusted her. When they had finished their rounds, she told him through her tears, it was already dark and dinner time and Miriam had offered to turn both cans in to the treasurer at the central collection point, near where she lived.

Sigerius was livid. “My daughter is standing here in the living room bawling,” he said to the chairwoman. “I know Joni inside out, your accusations are premature and totally out of line. I guarantee you my daughter is not going around plundering charity collection cans.” They agreed that he and Joni would go together so she could tell her side of the story, a suggestion she accepted with a pout, but she backed out just as he was about to leave for the gym. She was afraid she’d burst into tears. Or explode in anger. So he went alone. It was an onerous meeting; the woman insisted that it was Miriam’s word against Joni’s, and he was adamant that Joni’s name be cleared. When he returned home at ten-thirty that night, he told Joni he’d given them the choice: either take her word for it, or that was the end of the training, and then we’d have to see whether she stayed in the club.

He can still remember exactly where they were standing: in the front hall, he with his coat still on, right foot on the open spiral stairs; Joni halfway, holding her toothbrush with toothpaste already on it. He won’t soon forget the moment she broke. After he’d finished his report she went quiet. Then she slumped down onto a step, dropped the toothbrush, tick, tack, tock, onto the slate floor. She hid her face in her nightie and said with a drawn-out sigh: “Dad?”

He raised his eyebrows.

“Listen, Dad, don’t freak out or anything. I, um, what I mean is… well, actually, Miriam’s telling the truth.”

From Bonita Avenue, published by Pushkin Press. Translated from the Dutch by Jonathan Reeder.

Peter Buwalda is a Dutch novelist and formerly a journalist and editor. Bonita Avenue, his debut novel, was an immediate bestseller in Holland and nominated for a dozen prizes, winning three. It is a suspenseful psychological drama about the dark side of human nature, in which relationships, families and minds unravel in a web of murder, secrets and eroticism. Look out for our interview with Peter in the next issue of Bookanista. Read more.

Peter Buwalda is a Dutch novelist and formerly a journalist and editor. Bonita Avenue, his debut novel, was an immediate bestseller in Holland and nominated for a dozen prizes, winning three. It is a suspenseful psychological drama about the dark side of human nature, in which relationships, families and minds unravel in a web of murder, secrets and eroticism. Look out for our interview with Peter in the next issue of Bookanista. Read more.

Author portrait © Mikel Buwalda