Imagining the unthinkable

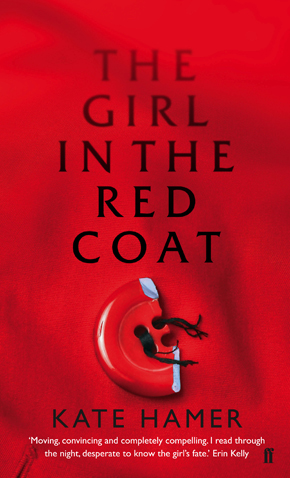

by Kate HamerThe Girl in the Red Coat begins with that premise – a missing child – that strikes fear in the hearts of any parent. It’s not anything I particularly intended to write about at all. But once the story came to me I found it difficult to stop. The idea first came to me as an image. A girl standing in a forest wearing a red coat. The image is not static, it’s moving – a bit like a piece of film would do. I only knew one thing for certain in it – the girl is lost in some way. Some time after having that image the first chapter of the novel came to me in one go. I sat up and wrote it late into the night, but the voice in that first chapter was not the girl, but her mother Beth. It’s Beth talking about her loss. In that first chapter we’re not quite sure what has happened but she’s writing about her daughter Carmel who she hasn’t seen for some time, for whatever reason. At that point I wasn’t sure of the reason either – and the mission of the book was to find out.

This is as much of the plot I can easily talk about without giving away a spoiler. Eight-year old Carmel is on a day out at a storytelling festival with her mother Beth when the unthinkable happens – she loses sight of her daughter. She stumbles around the field looking – some people are helpful and others stare at her blankly or worse. I found that I was almost breathless as I wrote these scenes. Time and again I thought, “You can’t do this to them, this is too awful!” But I had to pull myself up short – “they’re characters,” I reminded myself at the end of every day. But the question remained, if the premise was such a difficult one why engage with it?

Of course, it’s not the first book to deal with the subject by any means. I tended to actually avoid others covering the same ground as I wrote the book, not wanting to be influenced. I still haven’t read Ian McEwan’s The Child in Time although he is one of my all-time favourite contemporary writers. I’d read Emma Donahue’s Room some time before and thought it a very fine, if terrifying, book – but I didn’t return to it all the time I worked on The Girl in the Red Coat. I very much felt like Beth and Carmel’s very own, personal journey had to be unique to them and right from the start I didn’t want anything else to enter the mix that might throw the story off-kilter.

The subject is of course a universal fear for parents and to a certain extent I think in writing you are ‘working through’ your own fears, if that doesn’t sound too much like psychobabble. So that certainly played its part but I think there were other factors in my choice of story too.

I wanted this book to reflect the modern reality of mothers and daughters and not some chocolate-box version that we are served up on Mother’s Day.”

The relationship of mothers and daughters is crucial to the book and one of the strands that I really wanted to explore. The book opens with a close, loving relationship between the two but one that is already being tested. Beth is in mourning for a marriage that ended around a year beforehand and she is still really in love with her good-looking and charismatic ex-husband. As for Carmel, she may only be eight years old but already she is pushing the boundaries of the relationship with her mum. Sometimes she can be scratchy and impatient and feels her mother’s closeness to be claustrophobic. She craves it but pushes it aside at the same time. This is no perfect domestic scene with the serpent entering to destroy a vision of paradise. They are happy and not happy, as many families are at different times in real life. Underneath both are trying to do their best with the circumstances that have been presented to them. But, in the way of daughters, Carmel sometimes privately berates her mother for not being the perfect figure of motherhood, instead conferring the attributes of this on her friend Sara’s mother who wears lovely shoes and keeps an orderly and pleasant house. Sometimes she even wishes herself in that house where she imagines everything to be peaceful and conventional. Though Carmel also knows obliquely that her mother is really trying her best and feels guilty for her occasional disloyal thought or muttered aside.

I wanted this book to reflect the modern reality of mothers and daughters and not some chocolate-box version that we are served up on Mother’s Day. It’s one of the strongest bonds – but one that can be tested every day. In The Girl in the Red Coat it is of course tested to the very limit when Carmel is cruelly taken on a family day out. One can only imperfectly imagine Beth’s desperate, almost violent desire to look for her daughter as the bond that in some ways they have both taken for granted, because in normal family life that is what you mainly do, is ripped apart. To the point where her feet might be ripped to shreds; to the point almost to hallucination where she imagines her daughter as having dropped like a bracelet charm and where she will have to put her ear to the ground to hear Carmel’s cries that have become no louder than a mouse’s squeak.

It’s actually quite a hard book to talk about without giving away too much of the story. I would say though, that I think it goes in a direction the reader might not expect. It’s always a delight as a reader to be surprised and that’s what I hoped to do in the novel. I also hoped to take this tale of abduction somewhere that is not procedural and exists beyond news headlines. The title itself is part of that. I wanted to tap into the deep well of imagery that a child in a red coat conjures up, in film as well as literature. That way, the novel has the possibility of maybe becoming something bigger than itself by piggy-backing the resonances of what’s gone before. I love film and who can forget the strange little red-coated figure in Don’t Look Now who mysteriously appears all over Venice to the character played by Julie Christie? Is this an apparition, a tic of the psyche, or a real and sinister person appearing from the shadows of that city? When we learn that this woman’s own daughter has been drowned in a pond in the garden back home in England, the feeling of suspense and menace becomes almost unbearable. Or there’s another famous image – the little girl in the red coat that is the one spot of colour in the otherwise black-and-white world of Schindler’s List. In the film she is the one in the crowd we can mark out as a real individual all the way through their terrible collective journey. Somehow the symbolism of the red coat makes her into a universal figure at the same time.

Little Red Riding Hood (1881) by Carl Larsson. Wikimedia Commons” width=”290″ height=”232″>However there was one red-coated image lurking at the bottom of my subconscious that I was not quite aware of until the novel was long finished. I have an old Victorian fairy-tale print hanging in my hallway, looking out at me every day as I leave the house, and of course on one level Carmel is none other than Little Red Riding Hood. She has strayed from the path away from her mother’s watchful gaze. Now she is threatened by wolves.

Little Red Riding Hood (1881) by Carl Larsson. Wikimedia Commons” width=”290″ height=”232″>However there was one red-coated image lurking at the bottom of my subconscious that I was not quite aware of until the novel was long finished. I have an old Victorian fairy-tale print hanging in my hallway, looking out at me every day as I leave the house, and of course on one level Carmel is none other than Little Red Riding Hood. She has strayed from the path away from her mother’s watchful gaze. Now she is threatened by wolves.

As a child I read fairy tales constantly. The copy of Grimms’ Fairy Tales I had was from around the turn of the twentieth century. Goodness knows where it had come from. I think maybe my mother – a prolific and wide-ranging book buyer and lover – had bought a job lot of ancient children’s books in an auction or from a secondhand bookshop because it wasn’t the only book from that era. I also had a book of nursery rhymes with similar illustrations, a copy of The Water-Babies by Charles Kingsley. Alice in Wonderland, and Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island – what an incredible basis for anyone’s reading, let alone a young child. I still have a few of these books and even from the ones I no longer possess I can still vividly remember some of the colour plates. In my book of fairy stories no punches were pulled. Snow White was to have her heart ripped out by her jealous stepmother. The witch asks Hansel to stick his fingers through his cage so she can test the plumpness of his fingers to see if he’s oven-ready. Flesh gets torn by forests of thorns. Peril, menace, loss and betrayal abound alongside the tender hearts and swooning instances of love at first sight that is the lighter side of the fairy tale. So probably, like all writers and anyone trying a creative endeavour, my subject matter comes from multiple sources and you don’t always get to recognise them at first.

Is there really a trend for certain stories? Not just the missing person, at the moment the unsympathetic female protagonist is supposed to be having a field day. I love this latter genre, from Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl, the affectionately portrayed falling-down drunk in Paula Hawkins’ The Girl on a Train, to Rebecca Whitney’s imperfect and intriguing central character in The Liar’s Chair. Of course there is the literal mother of all unsympathetic women characters in Lionel Shriver’s We Need to Talk About Kevin. Once you start looking for a theme you’ll find it, though I do have a theory that ideas are out there in the ether and that’s why they can seem to cluster together.

Maybe genres are helpful but I’m not completely sure where my book would fit in. The Girl in the Red Coat has been described as a crime book, a psychological thriller and domestic noir. I’ve got no objection at all to these categories in fiction. They can be helpful as long as they are not too restrictively applied by publishers and readers who might otherwise enjoy straying from a well-trodden path. I actually think The Girl in the Red Coat could fit into any of those categories quite happily. Although my favourite description in a review so far has been as “a twenty-first century fairy tale.” I like that and it seems to perfectly express what I was trying to achieve in the book – something ancient and modern at the same time.

Kate Hamer grew up in Pembrokeshire. She completed a Creative Writing MA at Aberystwyth University and the Curtis Brown Creative novel-writing course, and won the Rhys Davies short story award in 2011 and had her winning story read on BBC Radio 4. She has recently been awarded a Literature Wales bursary and lives in Cardiff with her husband. The Girl in the Red Coat, her first novel, is published by Faber & Faber.

Kate Hamer grew up in Pembrokeshire. She completed a Creative Writing MA at Aberystwyth University and the Curtis Brown Creative novel-writing course, and won the Rhys Davies short story award in 2011 and had her winning story read on BBC Radio 4. She has recently been awarded a Literature Wales bursary and lives in Cardiff with her husband. The Girl in the Red Coat, her first novel, is published by Faber & Faber.

Read more.

Author portrait © Mei Williams