An instinct to play

by Gavin Maxwell and Mark AdlingtonVery few species of animal habitually play after they are adult; they are concerned with eating, sleeping or procreating, or with the means to one or other of those ends. But otters are one of the few exceptions to this rule; right through their lives they spend much of their time in play that does not even require a partner. In the wild state they will play alone for hours with any convenient floating object in the water, pulling it down to let it bob up again, or throwing it with a jerk of the head so that it lands with a splash and becomes a quarry to be pursued. No doubt in their holts they lie on their backs and play, too, as my otters have, with small objects that they can roll between their paws and pass from palm to palm, for at Camusfeàrna all the sea holts contain a profusion of small shells and round stones that can only have been carried in for toys.

The really steady play of an otter, the time-filling play born of a sense of well-being and a full stomach, seems to me to be when the otter lies on its back and juggles with small objects between its paws.”

Mij would spend hours shuffling a rubber ball round the room like a four-footed soccer player using all four feet to dribble the ball, and he could also throw it, with a powerful flick of the neck, to a surprising height and distance. These games he would play either by himself or with me, but the really steady play of an otter, the time-filling play born of a sense of well-being and a full stomach, seems to me to be when the otter lies on its back and juggles with small objects between its paws. This they do with an extraordinarily concentrated absorption and dexterity, as though a conjurer were trying to perfect some trick, as though in this play there were some goal that the human observer could not guess. Later, marbles became Mij’s favourite toys for this pastime – for pastime it is, without any anthropomorphising – and he would lie on his back rolling two or more of them up and down his wide, flat belly without ever dropping one to the floor or, with forepaws upstretched, rolling them between his palms for minutes on end.

Otters are extremely bad at doing nothing. That is to say that they cannot, as a dog does, lie still and awake; they are either asleep or entirely absorbed in play or other activity. If there is no acceptable toy, or if they are in a mood of frustration, they will, apparently with the utmost good humour, set about laying the land waste. There is, I am convinced, something positively provoking to an otter about order and tidiness in any form, and the greater the state of confusion that they can create about them the more contented they feel. A room is not properly habitable to them until they have turned everything upside down; cushions must be thrown to the floor from sofas and armchairs, books pulled out of bookcases, wastepaper baskets overturned and the rubbish spread as widely as possible, drawers opened and contents shovelled out and scattered. The appearance of such a room where an otter has been given free rein resembles nothing so much as the aftermath of a burglar’s hurried search for some minute and valuable object that he has believed to be hidden. I had never really appreciated the meaning of the word ransacked until I saw what an otter could do in this way.

This aspect of an otter’s behaviour is certainly due in part to an intense inquisitiveness that belongs traditionally to a mongoose; but which would put any mongoose to shame. An otter must find out everything and have a hand in everything; but most of all he must know what lies inside any man-made container or beyond any man-made obstruction. This, combined with an uncanny mechanical sense of how to get things open – a sense, indeed, of statics and dynamics in general – makes it much safer to remove valuables altogether rather than to challenge the otter’s ingenuity by inventive instructions. But in those days I had all this to learn.

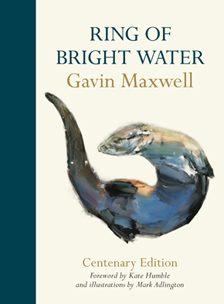

Images and text from the centenary edition of Ring of Bright Water, courtesy of Mark Adlington, the estate of Gavin Maxwell and Unicorn Press.

Gavin Maxwell was a Scottish naturalist and author born in 1914. Ring of Bright Water, first published in 1960, tells how he brought a smooth-coated otter back from Iraq and raised it in ‘Camusfeàrna’ (Sandaig) on the west coast of Scotland. Instantly hailed a masterpiece, it remains one of the most lyrical, moving descriptions of a man’s relationship with the natural world, and was made into a film starring Bill Travers and Virginia McKenna in 1969, the year of Maxwell’s death. The centenary edition of Ring of Bright Water, with illustrations by Mark Adlington, is published by Unicorn Press. Read more.

Gavin Maxwell was a Scottish naturalist and author born in 1914. Ring of Bright Water, first published in 1960, tells how he brought a smooth-coated otter back from Iraq and raised it in ‘Camusfeàrna’ (Sandaig) on the west coast of Scotland. Instantly hailed a masterpiece, it remains one of the most lyrical, moving descriptions of a man’s relationship with the natural world, and was made into a film starring Bill Travers and Virginia McKenna in 1969, the year of Maxwell’s death. The centenary edition of Ring of Bright Water, with illustrations by Mark Adlington, is published by Unicorn Press. Read more.

Mark Adlington is a London-based sculptor, painter and draughtsman. His wildlife research has taken him from Spain to Gran Paradiso, from Arabia to the coastline of the British Isles. The rapid sketches and footage he takes of his chosen subjects are then brought to the studio and absorbed into his finished paintings and large drawings. His collection of watercolours Still Bright Waters: A celebration of Gavin Maxwell’s Scotland was exhibited at the John Martin Gallery, Chelsea from 18 July to 8 August 2014.

markadlington.com