Jamie on the burger van

by Jim GibsonThere’s no one else to talk to so I might as well make the most of it. It’s a horrible thought but I can’t help thinking that his life is sort of like an animal’s, you know? Like he sort of doesn’t know he’s here and if he died tomorrow, he could still come down the next day and talk to me exactly the same as he does every day. I hand him a coffee. That’s why he comes back. For the free coffee. And to tell me the same stories he always does. About how he got to actually ride in an Eddie Stobart lorry once and how they’re having a party for his birthday at the home he lives in and how he knows one of the market traders sells dirty DVDs but you have to ask him for them. He points the stall out to me and I stand up to see where he means. I’m a lot higher than him in the van. The stall is empty, like a lot of them are now, and I wonder if he sees time the same way as me. I wonder if he sees the past in that empty stall. As he turns I see the big scar that travels down the back of his head like a map of a route down a mountain, with bulges on either side of it. I’ve never asked him what happened and never will. He sometimes calls me by a name that’s not mine and I assume it’s the name of whoever had a van parked up here a long time before me but there’s no way of telling.

The man from the e-cig stall comes over. He’s one to watch out for. Last time he hid a cock pump on the woman’s stall who sells curtains and that netting stuff that goes in the window. I’m sure her stock was all white when she first had it out but now it looks reclaimed from a heavy smoker’s house whose lungs finally gave way. It was quite funny when he did it though, hid the cock pump, he kept looking over to me, smiling and winking when the old people were looking around. That’s all you get on the market, really: old people. I get a few younger ones on their lunch breaks and the e-cig man does too, but apart from that it’s mostly old people. Anyway, when it happened I saw this old lady hold it up and ask what it was. The e-cig man was in stitches so it was obvious who’d put it there but he didn’t care. I don’t think either the woman on the stall or the old lady worked out what it was but he enjoyed it anyway. He asks me how trade is going and I tell him Same as usual: shit. What about you? He says he’s not doing bad but I know it’s not true cos I’ve only seen about 2 people go up all day. Town’s littered with e-cig shops now anyway, they’re nearly on par with charity shops. He slides some coins onto the counter and I chuck a burger on the griddle. It’s only enough for a cheese burger but I always stick a few bits of bacon on.

He always used to tell stories and drink red wine from a polystyrene cup; stories about how it used to be. I remember him from way back when I was at school and we’d sneak out at dinnertime to get a cheap spud from him for a quid.”

He asks me if I’ve heard ote of him who used ta stand over there, and nods his head to the empty spot next to me. There used to be a jacket potato van with a funny little man running it who only ever wore a black shirt and trousers, had slicked back hair and a chain around his neck with a cross on it. He always used to tell stories and drink red wine from a polystyrene cup; stories about how it used to be. I remember him from way back when I was at school and we’d sneak out at dinnertime to get a cheap spud from him for a quid. Anyway, he’s not allowed back now for cutting someone’s hand with a knife. The fella was kicking off about not getting enough cheese and reached over to grab some more. A big chap in a vest and shorts with tribal tattoos up his neck. One of the steroid kinds. The spud man didn’t seem to care; he slashed his hand and blood pissed out everywhere. I had to grab my first aid kit and bandage him up cos the spud man sort of saw it as ‘problem solved’. I remember being surprised that the big youth didn’t do more to kick off, I’m guessing there must have been more truth in the spud man’s big tales than I’d gave him credit for. I cob-up the burger and bacon and pass it over, saying No mate, not a word. He snorts a laugh: Fuckin nut job and walks back off to his stall.

I know it’s not going to last, sitting out here, but it’s turned into more of an obsession than a living. It’s like I’m present at the collapse of something that no one cares about. There’s a few fancy new stalls that come from time to time, you know, artisan bread and, like, trays of olives, but they never seem to stick it for more than a few weeks. A bit like I should have done; gone to find a busy lay-by or summet. The only time I’ve seen it really busy in ages was when there were people raising money for the funeral of a young lad who’d been knocked off his motorbike by a white van. The whole of town was out to buy some stuff and support it and they’d sold out of the raffle tickets by 12 which is unheard of. Everyone knew that the lad was a right sort but you can’t say that when they’re dead, can you? The veg lady told me how she felt sorry for the van driver and I looked at her with a question mark and she told me that it wasn’t his fault. The lad was one of these who drive around the estate at silly speeds doing wheelies and that he went straight over the give way bit when the van went into him and killed him. She said the van driver beat himself up about it and was getting threats left, right and centre. It sounded like he’d got a shit deal but it’s safer not to choose a side on stuff like this.

I know it’s not going to last, sitting out here, but it’s turned into more of an obsession than a living. It’s like I’m present at the collapse of something that no one cares about. There’s a few fancy new stalls that come from time to time, you know, artisan bread and, like, trays of olives, but they never seem to stick it for more than a few weeks. A bit like I should have done; gone to find a busy lay-by or summet. The only time I’ve seen it really busy in ages was when there were people raising money for the funeral of a young lad who’d been knocked off his motorbike by a white van. The whole of town was out to buy some stuff and support it and they’d sold out of the raffle tickets by 12 which is unheard of. Everyone knew that the lad was a right sort but you can’t say that when they’re dead, can you? The veg lady told me how she felt sorry for the van driver and I looked at her with a question mark and she told me that it wasn’t his fault. The lad was one of these who drive around the estate at silly speeds doing wheelies and that he went straight over the give way bit when the van went into him and killed him. She said the van driver beat himself up about it and was getting threats left, right and centre. It sounded like he’d got a shit deal but it’s safer not to choose a side on stuff like this.

The man with the scar hasn’t said a word for a long while but still stands in front of me. He’s facing away and sipping the coffee that looks far too hot to drink. He turns and looks straight at me with those deep eyes and I get the feeling that, if he was to not come down one day, then I’d disappear like the stall that sits empty. Like I’m only here in his memory. He blinks and doesn’t say a word and I can feel the atoms in my body shudder. He puts his drink onto the counter and walks away and for some reason I know that he isn’t going to come back again. I look out the open back door of the van, past the generator that vibrates and hums, into the graveyard of the church that’s directly behind me. There’s a statue of an angel holding a baby in amongst the overgrown and fading gravestones, Her face has been worn away and Her arms are chipped.

It’s nothing that a burger and a weak cup of tea can fix.

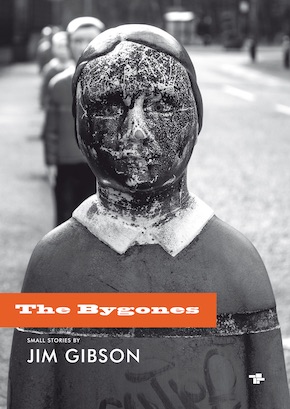

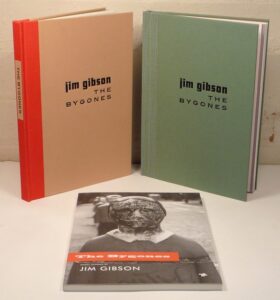

from The Bygones (Tangerine Press)

Jim Gibson grew up in the feral plains of an ex-mining village, Newstead. In the shadow of Lord Byron’s grandeur, he was part of a hand-to-mouth existence that was (and is) ignored by the media. Editor and co-founder of Hi Vis Press, he tries to encourage the lesser-voiced truths of our society. The Bygones, his first full-length collection, is published by Tangerine Press in trade paperback and in limited numbered, lettered and signed editions featuring illustrations by Julia Soboleva.

Jim Gibson grew up in the feral plains of an ex-mining village, Newstead. In the shadow of Lord Byron’s grandeur, he was part of a hand-to-mouth existence that was (and is) ignored by the media. Editor and co-founder of Hi Vis Press, he tries to encourage the lesser-voiced truths of our society. The Bygones, his first full-length collection, is published by Tangerine Press in trade paperback and in limited numbered, lettered and signed editions featuring illustrations by Julia Soboleva.

Read more

jimbobiliscious

@jimmmmmbo

@hi_vispress

@TangerinePress

Author portrait and cover image of defaced bollard outside Newstead Village Primary School © Sophie Gibson