A road less travelled

by Jason HewittWhen, in May 2013, in the middle of a deserted Polish forest 662 miles from home, I found myself being pulled to the ground by a salivating Alsatian intent it seemed on either wrestling the bag from my back or sinking its teeth into my arm, I remember very clearly having two distinct thoughts. One, perhaps unsurprisingly, was that I was about to be mauled to death by a (probably rabid) dog and that, as I’d failed to tell anyone where I was going, the remnants of my body would most likely never be found. The second was that researching a novel on location is all well and good but perhaps, just this once, I’d gone a step too far.

Let’s face it, in this age of the internet, Wikipedia and Google Maps, you could probably write a pretty good story, rich in detail, without needing to open a book, let alone leave your armchair. Award-winning novelist and agoraphobic Stef Penney famously wrote The Tenderness of Wolves by doing all her research in the British Library and not once visiting Canada where the novel is so convincingly set. Now, don’t get me wrong, I’m a huge fan of the British Library but if I’m going to set a novel in a specific location I need to see it for myself. It’s not just that I don’t trust myself to otherwise get the details right; it’s also that most of my scenes (and even characters) come to me ‘on location’. The research trip, for me, is the most exciting stage in the development of any novel – it’s when my mind truly opens up to the story and the ideas, like seeds on the wind, start to blow in.

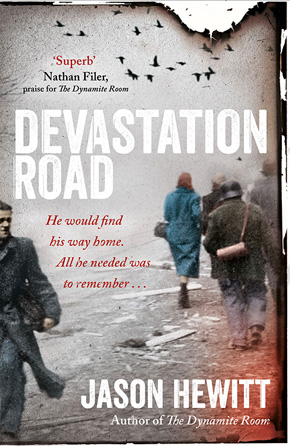

My new novel, Devastation Road, is essentially a road trip. It follows a character called Owen who wakes up in a field in May 1945 – days before peace is declared – only to discover that he’s not in England but Czechoslovakia, and that he has somehow lost three years of his memory and has no idea of how he got there. The novel, hereafter, is about his attempt to get home, whilst trying to piece his own story together as he goes. I can’t say much more than that but I can tell you that Owen’s journey takes him from the Sudetenland into the eastern corner of Germany (now Poland), before he heads west across the war-ravaged remnants of Europe, homeward bound.

It’s a densely wooded region that, as I walked through it, had a strange otherworldliness to it, a landscape steeped in folklore that seemed well suited to Owen’s mental state.”

Before even an approximation of his journey was fixed I knew that I’d not be able to write the story without taking the route myself. In fact it took two trips. The first – an initial recce – took place in May 2013 and deliberately spanned the same calendar dates as the novel takes place over so that I could note exactly how the countryside looked. The second trip was carried out four months later and this allowed me to revisit locations with a rough first draft to firm up the details, and visit new locations that I had added during the initial writing.

Before even an approximation of his journey was fixed I knew that I’d not be able to write the story without taking the route myself. In fact it took two trips. The first – an initial recce – took place in May 2013 and deliberately spanned the same calendar dates as the novel takes place over so that I could note exactly how the countryside looked. The second trip was carried out four months later and this allowed me to revisit locations with a rough first draft to firm up the details, and visit new locations that I had added during the initial writing.

It’s fair to say my May trip got off to a false start. I flew into Prague and took a train to Mělník, a quaint market town midway between Prague and Germany, but it felt too far from the border to be feasible for the story. Instead I moved north to Ústí nad Labem, an important industrial town within the heart of the once-Sudetenland; and it was using Ústí as a base that I first discovered the Ore Mountains and Bohemian Uplands, the latter characterised by the cone-shaped hulks of former volcanoes.

From Ústí nad Labem, my journey then took me north to Děčín, then east towards Liberec and into the Jizera Mountains that sit just beneath the nub of what is now the Czech/Polish border. It’s a densely wooded region that, as I walked through it, had a strange otherworldliness to it, a landscape steeped in folklore that seemed well suited to Owen’s mental state, and I decided to incorporate this in to the early sections of the novel.

The further I travelled, walking along rivers and through woods, just as Owen does, and jotting down everything that I saw, the more acutely aware I became of how alone I felt, how empty the landscape could seem and, yet it was still littered with signs of human life – boulders with white painted faces on them, forgotten oil lamps squatting in the forks of trees, even an abandoned chair by a woodland pool. Almost everything in the novel is inspired by something I saw. It was this sense of human abandonment that I tried to bring into the novel’s opening chapters. Across the whole of Europe in May 1945, with the Red Army pushing from the east and the Americans from the west, thousands of people found themselves fleeing for their lives, many travelling, staying hidden, through Europe’s woods and forests, and yet leaving, unbeknownst to them, signs that they had been there.

A number of the key scenes in Devastation Road are set in locations found on these travels. Some will be well known and were planned. Others were stumbled across by accident. The detail of a scene in an abandoned house, for example, comes directly from a building that I found on a river, just as it is in the story. Amongst the rubble and dust inside I sat on the floor and noted everything as Owen would see it: the light coming through the broken window, the scars in the wall where the cement rendering had peeled away like flaking scabs.

A number of the key scenes in Devastation Road are set in locations found on these travels. Some will be well known and were planned. Others were stumbled across by accident. The detail of a scene in an abandoned house, for example, comes directly from a building that I found on a river, just as it is in the story. Amongst the rubble and dust inside I sat on the floor and noted everything as Owen would see it: the light coming through the broken window, the scars in the wall where the cement rendering had peeled away like flaking scabs.

Eventually Owen heads into Germany, crossing the rivers Neiβe, Spree and Elbe, and joining the road to Leipzig, and I did the same. By then I was beginning to feel a similar alienation to Owen’s, the same disconnect from the world around you that comes from spending so long in countries where you don’t speak the language and communication issues render you almost mute. I became aware of myself falling deeper and deeper into my head.

In Leipzig’s City museum though, I made an important discovery – a sign that had been found at the location of the US Military Government that had resided in Leipzig from April to July 1945, when the US Army were forced to retreat to their agreed zone and allow the Russians in. When I returned in September I found the street, and stood outside the exact address, firming up the details of a roughly drafted scene. I crouched, hiding, on the corner of Leibnizstraβe and Gustav-Adolfstraβe just as one of my characters does. Passers-by must have thought I was mad but with a little imagination I could feel the flurry of emotions that my character feels with his back pressed to the wall as he hears the sound of lone footsteps echoing down the empty street, a jeep pulling away.

Taking my first research trip with no knowledge of Czech or Polish (and only a smattering of GCSE German) it was easy to understand how isolated, in moments like this, Owen would feel. One evening on a station platform in Forst, I had to put my trust in the hands of a Polish woman who spoke no English at all. The train that should have taken me into Poland had been delayed for over an hour and then, after several announcements that I didn’t understand, was finally cancelled. I was on a tight schedule though and by hook or by crook I had to reach my destination and that night’s hotel. Thankfully this woman took pity on me, and with barely a word between us helped me to find a suitable bus within the busy streets of the town, whilst I ambled, almost dazed, behind her. I put my trust in her entirely. I didn’t know what else to do. Owen, I realised later that night, would need to do the same – to find a character that he would have no choice but to rely on; to form an unlikely relationship with someone without the benefit of words. From this realisation, Owen’s counterpoint, a Czech boy called Janek, started to form in my head.

By the time of my second trip in September Janek was beginning to develop. To get truly into his head though, I decided to learn Czech. To be fair, much of what Janek says in the novel was not covered in our classes (which naturally leant more heavily towards asking directions to the post office than about wartime escapades) but it did help me to inhabit his character more effectively as well as teaching me how he would pronounce everything that he says.

I ate my goulash in the Egyptian-themed restaurant and spent the evening walking around the town’s visiting funfair where a disturbing number of sweet stalls were selling plastic Kalashnikovs filled with Smarties.”

If I had really gone method on my trips I would have walked down the Berlin–Hanover autobahn that by May 1945 was pitted by bomb blasts and strafed with bullet holes, or camped in fields, but I didn’t. For me it was all cheap hotels and dingy B&Bs. In Żagań, Poland, I stayed in the Hotel Willa Park that had been a German girls school and then the local headquarters of the residing Russian regiment. I ate my goulash in the Egyptian-themed restaurant (I kid not) and spent the evening walking around the town’s visiting funfair that was crammed into every narrow street and included a disturbing number of sweet stalls selling plastic Kalashnikovs filled with Smarties. All of this will be material for another novel I’m sure but it also compounded my own growing sense that I was out of my normal space and time, just as Owen is, and slowly disconnecting from a world he doesn’t recognise. It made me think of Robert Reid, the former BBC war correspondent, who said just before VE Day that in Europe there was “a sort of Alice in Wonderland air”. It was a quote that haunted me throughout my whole journey and seemed just as pertinent to me travelling through Europe in 2013, as it would have done in 1945.

Which brings me back to the Alsatian. The following day I left Żagań, and in a nearby forest I wandered around the remains of a prisoner-of-war camp. I’d been there for several hours, taking photographs, writing notes, and had not seen a soul. There were just the stone foundations of a few remaining barracks, and I crept around from tree to tree, listening to the crunch of pine needles beneath my feet, trying to imagine my characters moving through a scene I was tentatively planning. I didn’t see the dog until it was already hurtling towards me down the forest path, picking up pace faster and faster. It’s amazing how fast an Alsatian can run when it’s got you locked in its sight. I was vaguely aware of a figure ahead appearing through the trees – he looked like a farmer – and then yelling. I’d like to think that he was trying to call the speeding dog off me but he might have been yelling at me. Then, before I knew it, the Alsatian was on me. It came at me full pelt; its teeth suddenly at my bag and it knocked me to the ground. What happened next? I’m not sure. The first of the two thoughts I had – that I was going to be mauled to death – landed fast, and there was a lot of furious bellowing from the Polish man, so furious in fact that the dog eventually let me go, and I pulled myself up. The dog was called over and given a half-hearted wallop and then sent running off again. The man ambled after him and away again through the trees. He said nothing to me, not an apology, and I said nothing to him. Neither of us perhaps had the words, and, anyway, my heart was beating far too hard for me to speak. Only much later did it dawn on me that the Alsatian had probably wanted the Polish salami in my bag.

Which brings me back to the Alsatian. The following day I left Żagań, and in a nearby forest I wandered around the remains of a prisoner-of-war camp. I’d been there for several hours, taking photographs, writing notes, and had not seen a soul. There were just the stone foundations of a few remaining barracks, and I crept around from tree to tree, listening to the crunch of pine needles beneath my feet, trying to imagine my characters moving through a scene I was tentatively planning. I didn’t see the dog until it was already hurtling towards me down the forest path, picking up pace faster and faster. It’s amazing how fast an Alsatian can run when it’s got you locked in its sight. I was vaguely aware of a figure ahead appearing through the trees – he looked like a farmer – and then yelling. I’d like to think that he was trying to call the speeding dog off me but he might have been yelling at me. Then, before I knew it, the Alsatian was on me. It came at me full pelt; its teeth suddenly at my bag and it knocked me to the ground. What happened next? I’m not sure. The first of the two thoughts I had – that I was going to be mauled to death – landed fast, and there was a lot of furious bellowing from the Polish man, so furious in fact that the dog eventually let me go, and I pulled myself up. The dog was called over and given a half-hearted wallop and then sent running off again. The man ambled after him and away again through the trees. He said nothing to me, not an apology, and I said nothing to him. Neither of us perhaps had the words, and, anyway, my heart was beating far too hard for me to speak. Only much later did it dawn on me that the Alsatian had probably wanted the Polish salami in my bag.

On a warm Thursday in September, at an outside café in a German town, I wrote one of the final scenes exactly where it takes place, staring out across the water towards the town’s City Hall. On 19 May 1945, my characters would have seen British tanks in the square, beneath the glinting clock tower, but as I sat at the table and wrote their last lines, there were just city workers and shoppers going about their day, an atmosphere of strange normality that somehow seemed a fitting end. We, Owen and I, had taken the adventure together – not quite the adventure that Owen has in the novel but instead a secret one that only he and I will truly share. I like to think that somewhere on that journey, along roads and river, through fields and forests, I found him – a real sense of who he is. I doubt, somehow, that I would have done that at home sat in an old armchair.

Jason Hewitt is an author, playwright and actor. He was born in Oxford and lives in London. His debut novel, The Dynamite Room, was longlisted for the Desmond Elliott Prize and the Authors’ Club First Novel Award. His second novel, Devastation Road, is out now from Scribner UK/Simon & Schuster in hardback and eBook.

Jason Hewitt is an author, playwright and actor. He was born in Oxford and lives in London. His debut novel, The Dynamite Room, was longlisted for the Desmond Elliott Prize and the Authors’ Club First Novel Award. His second novel, Devastation Road, is out now from Scribner UK/Simon & Schuster in hardback and eBook.

Read more.

jason-hewitt.com

@jasonhewitt123

Author portrait © Philippa Gedge