A bookshop like no other

by Jen CampbellAh, Paris. The city of love and food and books. Abundant with literary cafés and penniless poets. Home of Le Procope, the city’s oldest restaurant still trading, founded in 1686, where Voltaire is supposed to have drunk forty cups of coffee a day.

Also home to Bar Hemingway, at the Ritz Paris Hotel. So called because, when the Nazis surrendered their control over the city on 25 August 1944, Ernest Hemingway was nearby, working as a war correspondent, and was desperate to ‘officially’ liberate somewhere. There are many different accounts of this – one being that he was late because he’d been too busy filling his car with champagne – but the one I like best has it that Hemingway arrived at the hotel, ran up on to the roof and fired a round of shots into the sky, before haring back down to the bar. Declaring the hotel liberated from the Nazis, he then ordered fifty martinis to be shared out amongst the guests. Apparently the martinis weren’t that great: the barman couldn’t be located, and they had to mix the drinks themselves.

All along the right bank of the river Seine, from Pont Marie to the Quai du Louvre, and on the left bank from the Quai de la Tournelle to Quai Voltaire, you can find the Bouquinistes. These are second-hand and antiquarian bookselling stalls which were set up by travelling pedlars in the sixteenth century. In the next century the pedlars were driven out of the city and made to re-apply for their stalls, to ensure they met censorship regulations. Strict rules of this sort didn’t go away: in 1810 Napoleon made all booksellers apply for a licence to trade. They had to hand in four morality references, to be certified by their local mayor, to prove they weren’t planning to sell rebellious publications.

These days France still has the equivalent of the UK’s old Net Book Agreement, meaning that discounting new books is banned – bar a 5% discount for students – and its current Culture Minister, Aurélie Filippetti, is determined to help bookshops thrive. On my most recent visit to Paris in 2013 there were at least twenty bookshops scattered around our hotel, and it was lucky for my bank balance that most of these only stocked books in French. A particularly lovely bookshop is Le Monte en l’Air, which serves as bookshop, café and gallery. The Abbey Bookstore, at the other end of the scale, is a second-hand English bookshop so full of books I wonder if it isn’t breaking the laws of physics. To my amazement, I discovered that there are bookshelves behind its bookshelves: the bookcases on the wall slide sideways, like French windows, revealing layers of books beneath.

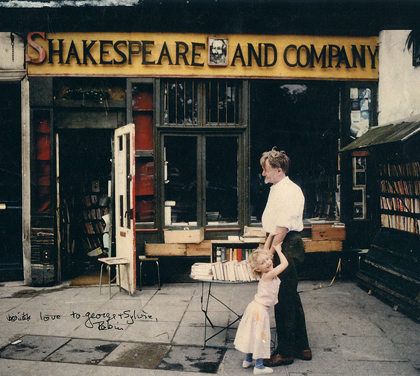

My favourite place of all, though, is Shakespeare and Company.

In 1917 an American woman called Sylvia Beach came to Paris to study French literature. She stumbled across La Maison des Amis des Livres, a bookshop run by Adrienne Monnier, a French poet and publisher who was one of the first women in France to open her own bookshop. As was common in those days, Adrienne also ran a subscription library out of her shop, which Sylvia joined. The two became great friends and were later in a relationship, living together for over thirty years.

Adrienne inspired Sylvia to open her own bookshop, which she called Shakespeare and Company. Initially it was tiny, but in May 1921 it moved to 12 rue de l’Odéon, opposite Adrienne’s bookshop, where it flourished. Sylvia’s main aim was to make her bookshop a space for writers to come and congregate, and come they did. Authors such as Ernest Hemingway, T.S. Eliot, Ezra Pound and F. Scott Fitzgerald were regulars, and James Joyce even used the bookshop as his office. Sylvia became Joyce’s secretary, editor and publisher, printing Ulysses when English and American publishers had refused to on grounds of obscenity.

During the occupation of Paris in the early 1940s, a Nazi soldier came to Shakespeare and Company and tried to buy a copy of Finnegans Wake. Sylvia refused to serve him. The officer said he would come back with his troops and burn the whole place down so, as soon as he left, Sylvia and her friends hastily removed all the books from the shop, and boarded it up. She never re-opened.

In 1951 another American moved to Paris to open an English bookshop. This was George Whitman, and his bookshop was called Le Mistral. He opened it on the Left Bank, right next to Notre-Dame, in a building that was once part of a sixteenth-century monastery. Like Sylvia’s bookshop before it, Le Mistral became a hub for writers – in fact George often called it a social utopia masquerading as a bookshop. In 1964, after Sylvia Beach’s death, George changed the name of Le Mistral to Shakespeare and Company in her honour.

From the 1970s onwards, George allowed writers to come and stay in his bookshop, where thirteen beds were hidden in amongst the shelves, and it became known as the Tumbleweed Hotel. His only demand was that those who stayed pen their autobiography on a sheet of paper, and give it to him before leaving. George claimed that as many as 40,000 people, including writers of the Beat generation like Allen Ginsberg and William S. Burroughs, slept in the shop over the years.

The Tumbleweed biographies are a fascinating social account of young people travelling through Paris. Most of them are filled with literary aspirations and romantic dreams.”

His daughter Sylvia – named after Sylvia Beach – is now using some of these autobiographies to put together a book on the history of the bookshop. “The Tumbleweed biographies are wonderful,” she confirms. “They’re an oral history of the shop, and a fascinating social account of young people travelling through Paris. Most of them are filled with literary aspirations and romantic dreams; it’s touching to see how similar a twenty-one-year-old staying in 1972 is to one staying today. We continue this tradition and right now we are housing a French environmentalist writer, a Polish poet and an English actor. Over Christmas we usually have some regular Tumbleweeds who return. This year there was a Polish-English actress, a Cambridge student of Arabic, and an Israeli girl studying mathematics whose father also stayed at the same time. It definitely feels like an extended family, which is what my father used to tell me when I complained about being an only child.”

Much like his bookshop, George Whitman was eccentric. He had a terrible temper, read a book every night, and often shoved bank notes inside books behind the desk for safe keeping. Instead of trimming his hair, he’d burn the ends off using a candle, and he once threw a book out of a window at a customer because he thought they might enjoy reading it. The actor Owen Wilson was once in Paris filming Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris, and decided to venture upstairs at Shakespeare and Company in the hope of meeting George, who lived above the shop and at that time was spending most of his days in bed. George apparently glanced up, nonplussed: “Have you written a book?” he enquired. “No,” said Owen. George tutted, unimpressed, and went back to reading his book. He ruled his bookshop like a slightly dishevelled monarch, and everyone loved him for it. He died in December 2011 at the age of ninety-eight.

I first visited Shakespeare and Company after George’s death, where it’s now run by his daughter Sylvia. The poetry section is my favourite part of the shop: a little alcove sectioned off by a garden gate. There’s also a piano, and a Wishing Well, and ‘the Mirror of Love’ upstairs, where hundreds of notes have been left by customers. Notes haven’t just been put here, though – I picked up a copy of John Green and David Levithan’s Will Grayson, Will Grayson, and out of it fell a handwritten message from another customer: ‘Hello, fellow nerdfighter. You have good taste.’ This made me smile from ear to ear.

At the start of 2014, I had a chat with Sylvia, who has now been running the shop for the past nine years, and we talked about Shakespeare and Company’s plans for the future:

“In the early 2000s, I picked up a guide book on Paris and read the paragraph on Shakespeare and Company,” Sylvia told me. “To my dismay, it said we were ‘resting on our laurels’.

“I had just started working at the bookshop, my father was in his late eighties and struggling to run the shop in the way he used to, and it’s true that the stock and events were pretty poor. It was difficult for him to pass on the reins of his ‘rag and bone shop of the heart’, partly because it had been his life for over fifty years, and he ran it in his own, very unique way. I turned out to be equally stubborn, and there were moments when customers had to witness a family row over the installation of a telephone, or how to organise a section. These usually ended in laughter, and I hope my father would be happy with all the changes I’ve made now, including our sporadic literary festivals. I have always tried to respect the original idea, just polish the edges.

“When I take a little distance, I think the history just gives myself and the team I work with inspiration. Sylvia Beach was a dynamic and most wonderful, dedicated bookseller. My father had a unique way of running his shop which can be encapsulated in some of his sayings:

1. Be kind to strangers lest they be angels in disguise.

2. We wish our guests to enter with the feeling they have inherited a book-lined apartment on the Seine which is all the more delightful because they share it with others.

3. How he described the bookshop: Where the streets of the world meet the avenues of the mind.

“Like a literary Chelsea Hotel, I just want to expand on all the ideas that George put in place: a literary crossroads – Paris is ideal for that – where you can find a place to sleep, spend hours reading in the library, sip on good coffee in our new (upcoming) café, and watch an event, which could be a concert with Moriarty, a film screening with Vincent Moon, or Margaret Drabble reading from her latest novel.

“I’m not sure what my favourite part of the shop is. It could be the Wishing Well or the Mirror of Love. What I miss greatly when I am not there is the vibrant, electric energy the shop holds. For whatever reason, it definitely has a very strong spirit that is energising. I remember two French geographers who strolled into the bookshop and suddenly stopped still. ‘C’est incroyable!’ they exclaimed. Apparently there was a strong current of water rushing under the bookshop, and they said this gave a very particular energy to the place. I don’t know if that’s true but there is something, in the shadow of Notre-Dame and on the banks of the Seine, that continues to draw people to this place.”

Jen Campbell grew up in a small village by the sea in northeast England. After studying English Literature at Edinburgh University, she moved to north London to sell books and write stories. She works part-time at an antiquarian bookshop. Her first book, Weird Things Customers Say in Bookshops, was published in 2012 and was a Sunday Times bestseller, and was followed by a sequel in 2013. The Bookshop Book, the official book of the 2014 Books Are My Bag campaign, is published by Constable. Read more.

Jen Campbell grew up in a small village by the sea in northeast England. After studying English Literature at Edinburgh University, she moved to north London to sell books and write stories. She works part-time at an antiquarian bookshop. Her first book, Weird Things Customers Say in Bookshops, was published in 2012 and was a Sunday Times bestseller, and was followed by a sequel in 2013. The Bookshop Book, the official book of the 2014 Books Are My Bag campaign, is published by Constable. Read more.

jen-campbell.co.uk

Follow Jen on Twitter: @aeroplanegirl

The Bookshop Book tour

Jen Campbell talks about and signs copies of The Bookshop Book, in her UK-wide tour. Upcoming dates and venues:

Saturday 6 December: Pritchards, Merseyside

Tuesday 9 December: Notting Hill Bookshop

More info