The locusts

by Ahmed FagihAt that moment, Fagih Misbah came forth to speak in his inimitable fashion. He raised his hands as if to grab a bolt of lightning from the heavens, then opened his eyes crazy-wide, as he always did when invoking Shartookh and Shabrookh and the other creatures they call ‘My Friends, the Kings of the Djinn’. Creating a full-blown spectacle, he scattered drool and shook his thick white beard, invoking the will of Allah the Merciful, along with past prophecies about two great swarms of locusts sent to eat men and women and children alike. “The locusts,” the fagih shouted, “will beset animals, trees, castles – even pieces of metal!”

All of these frightful stories about locusts; the dangers of locusts… locusts… locusts… With the holy men standing there with angry, bronzed faces, the crowd felt in their hearts the looming disaster. The sheikhs’ talk had infused their core with a great odium. They felt now as if nothing could compare with this thing called locust: not death, not plague, not any other terrestrial catastrophe. An old man, caught up in the throes of an emotion that chilled those around him to the bone, suddenly called out for divine mercy: “Your grace, O Lord! Your forgiveness!”

There followed another voice, shot through with intensity: “What is in store for us now, my friends?”

And then another… “Yes, what do we do now?”

And all of a sudden there was a torrent of voices, a cacophony of floating question marks. Heads twisted in confusion. A mantra of distraction.

“What to do? What to do? What to do?”

After a while, the first thing that resembled a suggestion emerged from the lips of Fagih Misbah, who insisted there was no other option: they must all go to the tomb of Sidi Abu Kindil, illuminate for him candles, burn jawa incense, loban and fasuk1 – and entreat him to intervene with Allah to keep this danger at bay, so that they might all return to their houses to sleep in peace.

“Sidi Abu Kindil will not disappoint,” Misbah promised. “He will keep the locusts from the path of the village…”

Once the confusion settled and the villagers could begin to focus on the problem, Fagih Misbah’s proposition was quickly lost in a jumble of other suggestions. Among those offering alternatives was Omran, bound to be taken seriously for he was in his forties, meaning that he had surpassed the age of recklessness, and hadn’t yet made it to the age of feeblemindedness. Omran’s suggestion was that the villagers make fires in different places around the village. Perhaps, he reasoned, the locusts would change course once they saw the smoke. Since no one could see why this wouldn’t just create a temporary diversion, many craned their necks and traded looks, searching for better ideas. Defending his original idea, Omran waved his fist and shook his head in anger.

Mabrouk remained silent, head down, his body shaking uncomfortably as if he were sitting on top of a village of ants. He was twenty-five. The day his father passed away, Mabrouk inherited a big family and small garden. Though he worked like a dog, he was barely able to put food on the table. For the last few minutes, a thought kept echoing against the walls of his consciousness. The idea seemed to him at alternate moments to be so laughable, so absurd, he worried that if he dared speak it, the others would erupt into laughter and seriously question his capacity for rational thought. He continued to mull this idea over in his head, when someone elbowed him. The crowd wanted to hear what he thought of the idea Haj Salim had just put forth. Was it really possible that with banging bells and drums and the hollow chiming of empty glasses they might succeed in driving the locusts from the village? The crowd had begun to settle on this idea, and were now turning to Mabrouk for his opinion. He thought it was silly, but he recoiled from addressing the assembled crowd.

“Speak, ya Mabrouk. What’s in your head? You’re quiet… why?”

“You don’t like Haj Salim’s idea… is that because you don’t think it will work?”

In spite of himself, Mabrouk blurted out, “No, I don’t think it will.”

The group was shocked.

What is this, Mabrouk? What would you have us do, sign a contract with these monsters that are almost upon us not to harm other villages, where there are people and farms and beating hearts?”

Haj Salim, the author of the idea under consideration, winced and cast a disbelieving eye at Mabrouk.

“And how is this, that my idea will not work?”

“It won’t work,” Mabrouk said, “because when we divert the locusts from our village, they will go and find other villages filled with good people, and farms, and beating hearts.”

Hearing this, Haj Salim became defensive:

“What is this, Mabrouk? What would you have us do, sign a contract with these insects – the monsters that are almost upon us – not to harm other villages, where there are people and farms and beating hearts? We have not found a better suggestion…”

Mabrouk continued in spite of Haj Salim’s interruption, and no one interrupted. He was astonished to see people were straining to hear what he had to say. Once he finished, however, many gnawed their lips and exchanged incredulous glances, marks of stifled scorn.

Mabrouk attempted to bring the temperature down a notch, methodically adding more details:

“Tonight, in the pre-dawn hours, we must assemble two groups at the southernmost edge of the village. Two groups, mind you, as otherwise each will forget their empty bags. Each person must bring with him an empty sack. A battle awaits us that even past ages have not known. In this battle, sacks will be our weapons. We will make for the place where the locusts sleep. As we know, the locust does not stir until the sun’s rays rouse him. We will cram those sleeping locusts into our empty sacks and bags, then we will return and cook them in our black pots and pans. We will transfer the locusts from the dark recesses of our bags to the dark recesses of our bowels!” Here, Mabrouk concluded with delicious emphasis, “This will be the most wonderful extirpation that has ever been known in the history of locusts!”

At the conclusion of Mabrouk’s soliloquy, sarcastic commentary could still be heard bubbling from every corner of that small hall.

“This is an army, an army of locusts. Not a single locust or two locusts.”

“An army whose queen rules its throne,” said another sarcastically. Fagih Misbah took advantage of the shifting wind to remind the crowd of his original idea, exhorting a mass pilgrimage to the tomb of Sidi Abu Kindil, Sheikh of the Saints and the Virtuous Ones.

Just then, a heaviness fell upon the crowd, as darkness had arrived. Children called their fathers to dinner, with the age-old urging, “Mother says to tell you dinner is already cold…”

Mabrouk felt the crowd had not understood sufficiently what he had said, and that he must explain the idea better.

“Listen, brothers,” someone interjected, in a lull between cacophonies. “According to my thinking, the words of Mabrouk are not devoid of some logic… but this army of locusts… if it were to be spread above us, it would cover the sky itself.”

“Mabrouk has told us that these two groups, each of which does not exceed fifty individuals, will collect the locusts and then dispose of them. If you ask me, this is impossible,” said another.

Sheikh Masoud nodded, as if to fill the void.

“And why fifty men only? Why don’t we send the whole village, with its large and small, its old and middle-aged, its children and women, and all the shabab2? Everyone, absolutely everyone, should participate in this campaign.”

The silence that followed these words was deafening.

Sheikh Masoud had opened a new window on Mabrouk’s suggestion. Even a fly on the wall would have noticed: The crowd was almost sold.

The first to raise his voice in clear support was Haj Salim himself:

“I want to say there is absolutely nothing wrong with Mabrouk’s idea.”

“I swear by God that’s true!” said another.

“Why don’t we try this tonight? If it doesn’t work, we’ll go back to Haj Salim’s idea tomorrow.”

“We will kill two birds with one stone,” said a third.

“On the one hand, we will get rid of the locusts, and on the other we will be able to feed our children for two, perhaps three days.”

Only one person remained steadfastly against the plan.

“You are all crazy,” screamed Fagih Misbah. “There’s no doubt about it now, you are all completely mad!” he muttered as he struck the ground with his stick, then stormed out of the room, wondering how these people could shun his sage advice in favour of the ravings of a young upstart like Mabrouk.

And so the plan unfolded in the early hours of the morning, as a rooster somewhere first thought about stirring, as dogs bayed at the stars and the wind carried the howling of a lone wolf from a faraway place. The southern perimeter of the village witnessed a gathering unparalleled in the history of all the village gatherings. Their numbers were great, very great. Ashur managed to capture perfectly the thoughts running through everyone’s mind when he said he would never have imagined the village contained so many people. This was a motley crew of men, women, the old, whom time had bent forward, and the very young, whom the coldness of night couldn’t stop from jumping this way and that. Outwardly, the only attribute these individuals shared was an empty sack slung over each shoulder.

One woman brought with her a nursing baby. Amer came riding on his donkey. Abdul Nabi had even brought with him his small wheelbarrow, in which he would put two or three sacks of locusts. Dogs nipped at the heels of those bringing up the rear. The sounds of the treading of feet over vast areas of land mixed with the barking of dogs, the braying of the donkey and the clatter of the small wheelbarrow.

So it was that the villagers set off into winds laden with the scent of citrus. It would have been apparent to anyone watching that each individual was part of a whole. The unique scent that pervaded the place, an intermingling of orange blossom essence, sheaves of wheat, and balah3, was a symbol of unity. There was no full moon to light the way as they covered the ground, but the stars compensated, pulsing as if they were heaven’s very eyes, their luminescence dissolving pockets of darkness. When the group arrived at the area where the locusts slept, shafts of luminous dawn suddenly exploded from above, enabling the villagers to scoop up the nefarious insects with ease. The horizon simmered in ochre; the colour of burnt mountain-tops tapered off into a thin layer of blue, before being crushed by obsidian black. The heavenly aurora above carried within it something resembling a palpitation. One would have been forgiven for thinking that it was a great, living being.

Some raised their voices to deliver the satirical poetry they recited during the days of the war against the Italians, making plain the connection between this struggle and wars with guns and bullets.”

The locusts had chosen a wide hill upon which to make their bed. Under the light of dawn, it appeared as though it were an unending field of ready-to-harvest sheaves of wheat, caramelized to a golden hue. Here was the defining moment. The troops began their attack. Men doffed their cloaks and threw them into any number of heaps. They tied their belts around their bellies and readied their sun-scarred forearms, from which grew thick mats of hair. Those wearing baggy pants rolled up the bottoms, from the feet upwards. The mother of the newborn wrapped her bundle with care, kissed it, then laid it down in a safe spot under a tree. Amer tethered his donkey’s two forefeet and left the animal to eat its fill of grass. Some of the villagers had carried with them jugs of water; others, thinking ahead to the inevitable wailing of hungry children, carried with them small pails of loaves of hard bread. Food and water were distributed strategically across the battlefield. Soon all these details were forgotten. Everybody was engrossed, transfixed by the task before them, indifferent to thorns and jagged bits of rock which might cause their hands to bleed, to bugs and scorpions. All that concerned them now were the locusts before them and the need to gather them up before the sun had a chance to warm their carapaces. Children stepped out tentatively in between the feet of the advance guard only to retreat suddenly, frightened by the clamour of a copious shooing. One old woman, Saida, never stopped shouting, all the while urging them on, insisting that they find the locust queen. In places along this human phalanx, villagers started singing. Some sang the harvesting song. Some of the sheikhs raised their voices to deliver the satirical poetry they recited during the days of the war against the Italians, in so doing making plain the connection between this struggle in which they were engaged, and wars with guns and bullets. The voices rose, singing…

“We are fighting the enemy amongst us… our boys are brave… our boys…”

In another spot, others sang in unison… “Moon on high… travel on, come here…”

The younger children, too young to have been exposed to these patriotic anthems, found something hidden in the nearby chasms: echoes, curious and beautiful, set off by the singing. The children strained to hear, their small black eyes open with fascination. Then they howled in unison:

“Haww, awww…”

And the echo responded…

“Hawww, hawwww…”

Standing astonished, they all laughed and clapped in overwhelming joy, as if they had stumbled upon the greatest discovery in the world.

Throughout all this, the locusts were calm and still, as if already dead. The human chain advanced inexorably. The mass of villagers appeared at times like a never-ending line of soldiers, at others like a winding snake ingesting a huge, wide carpet. Each of the members of the chain silently wished it possible to widen the line or multiply their numbers, so they might scoop up yet more locusts.

When the hand of the old farmer reached out to snatch a group of locusts in front of Omran, the zeal of the two was so great that a fight might have broken out if the old man hadn’t withdrawn his hand in time. Some of the sheikhs present seemed to be off in some parallel universe, channelling rage at past injustices. It was as if they had had with these creatures something approximating a blood feud, and how sweet was the revenge! Voices cried out from everywhere, urging the group to redouble their efforts. The most insistent of them all was Sheikh Masoud:

“Faster, fellows! Push forward!”

But look, the unfolding dawn revealed his mistake: half of his group was made up of women and children! And in one of the corners of the great line, euphoria overtook seven friends, among them Ashur. They agreed to make a bet, to see which of them could be first to the top of the hillock, each collecting locusts on his way.

Ashur’s six companions had exerted themselves to the point that, despite the cold weather, beads of sweat fell from their brows. Even so, Ashur took the early lead, cutting the distance in record time. Standing at the summit, he raised his hand in elation…

“Huyya, huyya!”

Ashur felt at this moment like a great leader in the throes of battle. After him came the others, their bags full of locusts. Before the sun could rise from behind the far-off mountain peaks, even those in parts of the line that lagged furthest behind had finished their mission. Everybody stopped to look at their catch and marvel at the miracle that had fallen into their hands. Their collective hearts were full of great pride. Each felt as if this miracle had fallen simultaneously upon him personally and the group. With that epiphany, and for the first time since the crisis began, smiles broke out all around. Under the light of early day, the sandy hill showed red. There was not a trace of the locusts that had lately covered it, save a few odd specimens jumping this way and that, trailed by hopping children. And there, look there… Haj Salim is surveying the scene, wondering how in heaven’s name they had managed to do what they had done. In the name of Allah, what had they done!

The women anticipated the moment they would arrive back at the village and could boil the locusts in their black pans. Finally, they could quell the children’s endless clamour for bread, of which there was never enough. Shortly thereafter, the children would discover that when boiled, those bottomless handfuls of locusts were so tasty! As the crowd, lugging locusts on backs and shoulders, returned to its small village, joy was in their minds as well as on their faces.

Every step was a pleasure! They marched, and they danced. There… Abdul Nabi with his small wheelbarrow containing three bags of locusts. Chasing a few children, he’s making car sounds as he moves… beep! Beep! The children burst out laughing.

Look over there at Ashur and his beloved donkey. Over that way, the mother carrying her newborn in her arms. What a beautiful sight. Oh, and over there, Ashur, winner of the bet, joking with his companions. To a soul, they loved their village, which now appeared to them a vision of green. Life-green. The sun was now at their backs, fashioning long shadows from their figures. Individual projections merged into one enormous silhouette, that of a single living creature, the largest the world had ever known.

Translated by Ethan Chorin

1 Other varieties of incense

2 Youth

1 Early-harvest dates

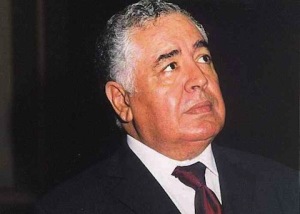

Ahmed Fagih was born in 1942 in the village of Mizda, 100 miles south of Tripoli. He worked as a journalist in Tripoli until 1962, when he won a scholarship to study theatre at London’s New Era Academy of Drama and Music. In 1972 he returned to Libya to head the National Institute of Music and Drama, in the same year becoming editor of the influential Al-Usbu’ Ath-Thaqafi (Cultural Weekly). Fagih’s major work, a trilogy with the English titles I Shall Present You With Another City, These Are the Borders of My Kingdom and A Tunnel Lit by a Woman, won the prize for best novel at the 1991 Beirut Book Fair. Collections of Fagih’s short stories include: Fasten Your Seat Belts (1968), The Stars Disappeared (1976), A Woman of Light (1985) and Mirrors of Venice (1997). Several of his novels have been translated into English, including Maps of the Soul (Darf, 2014) and Homeless Rats (Quartet, 2011). Fagih has had a long, parallel diplomatic career, having previously headed Libya’s missions in Greece and Romania. In the wake of the 2011 Revolution, he defected to the rebel government and continued as Libya’s Ambassador to the Arab League, based in Cairo.

Ahmed Fagih was born in 1942 in the village of Mizda, 100 miles south of Tripoli. He worked as a journalist in Tripoli until 1962, when he won a scholarship to study theatre at London’s New Era Academy of Drama and Music. In 1972 he returned to Libya to head the National Institute of Music and Drama, in the same year becoming editor of the influential Al-Usbu’ Ath-Thaqafi (Cultural Weekly). Fagih’s major work, a trilogy with the English titles I Shall Present You With Another City, These Are the Borders of My Kingdom and A Tunnel Lit by a Woman, won the prize for best novel at the 1991 Beirut Book Fair. Collections of Fagih’s short stories include: Fasten Your Seat Belts (1968), The Stars Disappeared (1976), A Woman of Light (1985) and Mirrors of Venice (1997). Several of his novels have been translated into English, including Maps of the Soul (Darf, 2014) and Homeless Rats (Quartet, 2011). Fagih has had a long, parallel diplomatic career, having previously headed Libya’s missions in Greece and Romania. In the wake of the 2011 Revolution, he defected to the rebel government and continued as Libya’s Ambassador to the Arab League, based in Cairo.

Ethan Chorin is an American businessman and writer. He was one of the first US diplomats posted to Libya after the lifting of UN sanctions, and returned to Benghazi after the 2011 Libyan Revolution as co-founder of an organisation working to build trauma capacity. In addition to Translating Libya, he is author of Exit the Colonel: The Hidden History of the Libyan Revolution (Public Affairs, 2012). A frequent commentator on Libyan affairs for the BBC, Chorin’s features and Op-Eds have appeared in international publications including The New York Times, the Financial Times, Forbes and Foreign Policy.

Translating Libya: In Search of the Libyan Short Story, edited by Ethan Chorin and with a foreword by Ahmed Fagih, is published by Darf Publishers in paperback, priced £8.99. Read more.