The man in the yellow suit

by Knut HamsunIn the middle of the summer of 1891 the most extraordinary things began happening in a small Norwegian coastal town. A stranger by the name of Nagel appeared, a singular character who shook the town by his eccentric behavior and then vanished as suddenly as he had come. At one point he had a visitor: a mysterious young lady who came for God knows what reason and dared stay only a few hours. But let me begin at the beginning…

It all started at six one evening when a steamer landed at the dock and three passengers appeared on deck. One of them was a man wearing a loud yellow suit and an outsized corduroy cap.

It was the evening of the twelfth of June; flags were flying all over town in honor of Miss Kielland’s engagement, which had been announced that day. The porter from the Central Hotel went aboard and the man in the yellow suit handed him his baggage. At the same time he surrendered his ticket to one of the ship’s officers, but made no move to go ashore, and began pacing up and down the deck. He seemed extremely agitated, and when the ship’s bell rang the third time, he hadn’t even paid the steward his bill.

While he was taking care of his bill, he suddenly became aware that the ship was pulling out. Startled, he shouted over the railing to the porter below: “It’s all right. Take my baggage to the hotel and reserve a room for me.”

With that, the ship carried him out into the fjord.

This man was Johan Nilsen Nagel.

The porter took his baggage away on a cart. It consisted of only two small trunks, a fur coat (although it was the middle of summer), a satchel, and a violin case. None of them had any identification tags.

He awoke from his thoughts with a violent start, so exaggerated that it didn’t seem genuine; it was as if the gesture had been made for effect, even though he was alone in the room.”

Around noon the following day Johan Nagel came driving down the road to the hotel in a carriage drawn by two horses. It would have been easier to make the journey by boat, but still he came by carriage. He had some more baggage with him; on the front seat was a suitcase, a coat, and a small bag with the initials J.N.N. set in pearls.

Before getting out of the carriage, he asked the hotelkeeper about his room, and later, on being taken up to the second floor, he began to examine the walls to determine how thick they were and whether any sounds could come through from the adjoining rooms. Suddenly he turned to the chambermaid and asked: “What is your name?”

“Sara.”

“Sara.” And without pausing: “Can you get me something to eat? Well, so your name’s Sara. Tell me,” he went on, “was there ever a pharmacy on these premises?”

Surprised, Sara answered: “Yes, but that was many years ago.”

“Oh, many years ago? I knew it the minute I came in; it wasn’t so much the smell, but somehow I sensed it.”

When he came down for dinner, he didn’t say a word during the entire meal. His fellow passengers from the day before – the two men at the other end of the table – made signs to each other when he came in, and made no effort to hide their amusement at his previous evening’s misfortune, but he took no notice of them. He ate quickly, declined dessert, and left the table abruptly by sliding backwards off the bench, lit a cigar, and disappeared down the street.

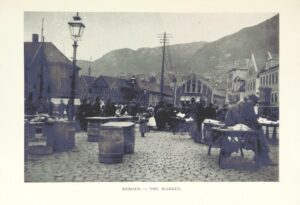

Bergen in the 1890s, from A Voyage to Viking-Land by Thomas Sedgwick Steele, 1896. British Library/Wikimedia Commons

He stayed out until long after midnight and didn’t return till a few minutes before the clock struck three. Where had he been? Only later did it become known that he had walked to the next town and back – along the same long road he had driven over that morning. He must have had some very urgent business there. When Sara opened the door for him, he was wet with perspiration, but he smiled at her and seemed to be in excellent spirits.

“My God, girl, what a lovely neck you have!” he said. “Did any letters come for me while I was out – for Nagel, Johan Nagel? Three telegrams! Oh, would you do me the favor of taking away that picture on the wall, would you? I don’t like to have it staring at me. It would really annoy me to lie in bed and have to look at it! Besides, Napoleon III didn’t have such a bushy beard, anyway! Thank you.”

When Sara had gone, Nagel remained standing in the middle of the room. He stood absolutely motionless, staring fixedly at a spot on the wall, and except that his head slumped more and more to one side, he didn’t move.

He was below average in height; his face was dark-complexioned, with deep brown eyes which had a strange expression, and a soft, rather feminine mouth. On one finger he wore a plain ring of lead or iron. His shoulders were very broad; he was between twenty-eight and thirty, but definitely not older, although his hair was beginning to turn gray at the temples.

He awoke from his thoughts with a violent start, so exaggerated that it didn’t seem genuine; it was as if the gesture had been made for effect, even though he was alone in the room. Then he took some keys, small change, and what looked like a lifesaver’s medal on a crumpled ribbon out of his pocket and put them on a table next to the bed. He stuck his wallet under the pillow, and from his vest pocket he pulled out a watch and a small vial labeled ‘poison’. He held the watch in his hand for a moment before putting it down, but immediately put the vial back in his pocket. Then he removed his ring and washed, smoothing his hair back with his fingers, never once looking in the mirror.

He was already in bed when he suddenly missed his ring, which he had left lying on the washbasin, and as though unable to be separated from this perfectly ordinary ring, he got up and put it on again. Then he began opening the three telegrams, but before he had finished the first one, he uttered a short, muffled laugh.

He lay there laughing to himself; his teeth were exceptionally fine. Then his face became serious again and a moment later he nonchalantly tossed the telegrams aside. Yet they all apparently dealt with a matter of great importance; they referred to an offer of 62,000 crowns for a country estate, the money to be paid in cash if the deal were concluded at once. They were brief, matter-of-fact business telegrams, definitely not sent as a hoax, although they were unsigned. A few minutes later Nagel fell asleep. The two candles on the table, which he had forgotten to put out, illuminated his clean-shaven face and his chest and quietly flickered on the telegrams, which lay wide-open on the table.

The three telegrams lay open on the table in his room for everyone to read; he hadn’t looked at them again since the night they arrived.”

The next morning Johan Nagel sent a messenger to the post office, who returned with some newspapers – several of them foreign – but no letters. He put his violin case on a chair in the middle of the room, as if he wanted to show it off, but he didn’t open it, and simply left it there.

All he did that morning was to write a couple of letters and walk up and down his room reading a book. He also went to a shop and bought a pair of gloves, and then wandered over to the marketplace, where he bought a little reddish-brown puppy for ten crowns which he immediately presented to the hotelkeeper. Everyone thought it very amusing that he named the puppy Jacobsen, although it was a female.

He managed to do nothing the rest of the day as well. He had no business to attend to in town, no offices to contact, and no calls to make, as he didn’t know a soul. The people in the hotel were baffled by his strange apathy toward everything, including his own affairs. The three telegrams lay open on the table in his room for everyone to read; he hadn’t looked at them again since the night they arrived. And sometimes, when asked a direct question, he didn’t even answer. Twice the hotelkeeper had tried to engage him in conservation to find out who he was and what had brought him to town, but both times Nagel had avoided the issue. Another instance of strange behavior occurred during the course of the day. Although he didn’t have a single acquaintance in town and had made no effort to get in touch with anybody, he had nevertheless stopped all of a sudden in front of one of the young ladies of the town at the entrance to the cemetery, fixed his eyes on her, and then bowed deeply, without a word of explanation. The young woman blushed to the roots of her hair, deeply embarrassed, whereupon the impudent fellow walked out of town on the main road, as far as the parsonage, and beyond. He did this several days in a row, always returning to the hotel after closing time, so that the front door had to be opened for him.

On the third morning, as Nagel was leaving his room, he ran into the hotelkeeper, who greeted him with a few pleasant remarks. They went out on the veranda and sat down; by way of making conversation, the hotelkeeper asked him about the shipment of a crate of fresh fish. “Do you have any idea how I should go about it?” he asked.

Nagel looked at the crate, smiled, and shook his head. “I don’t know anything about those things,” he said.

“You don’t? Well, I thought perhaps you had traveled a lot and had seen how they did it in other places.”

“No, as a matter of fact, I haven’t traveled much.”

Pause.

“Well, you’ve probably been busy with other things. Are you a businessman by any chance?”

“No, I’m not a businessman.”

“Then you didn’t come here on business?”

Nagel didn’t answer, but lit a cigar, inhaled deeply, and assumed an absentminded air.

The hotelkeeper was observing him out of the corner of his eye. “Won’t you play for us sometime? I see that you have a violin with you.”

“Oh, no, I’ve given that up,” Nagel replied in an offhand manner.

He got up and walked away rather abruptly, but a moment later he came back and said: “By the way, it just occurred to me, you can give me the bill any time you like. It makes no difference to me when I pay.”

“Thank you,” said the hotelkeeper, “but there’s no hurry. If you stay with us for any length of time, there will be a discount. Are you planning to stay for some time?”

Nagel suddenly seemed to come to life. His face flushed for no apparent reason and he quickly answered: “Yes, I may stay on here for some time; it all depends. Perhaps I didn’t tell you; I’m an agronomist – a farmer. I’ve just returned from abroad and I might decide to settle down here for a while. But perhaps I even forgot to – my name is Nagel, Johan Nilsen Nagel.”

He then heartily shook the hotelkeeper’s hand and apologized for not having introduced himself sooner. There was not the slightest trace of irony in his expression.

“I’ve been thinking that we might be able to find you a better room, a quieter one, said the hotelkeeper. “You’re close to the stairs now, and that can be rather noisy.”

“Thank you, but there’s no need for that. My room is quite satisfactory. Besides, I can see the entire town square from my window, and that is very pleasant.”

After a slight pause, the hotelkeeper continued: “So you are taking a brief holiday now? Then you’ll probably be here through the summer?”

“Two or three months, perhaps longer,” Nagel replied. “I don’t know for sure. It all depends. I’ll make up my mind when the time comes.”

‘A few days ago I saw something in the papers about a man who was found dead in the woods somewhere around here,’ Nagel said suddenly. ‘What kind of a man was he – Karlsen, I think his name was. Did he come from here?'”

At that moment a man walked by and bowed to the hotelkeeper. He was an insignificant-looking man, rather short and very badly dressed. He obviously moved with difficulty, but in spite of his handicap he was surprisingly agile. Although he bowed deeply, the hotelkeeper ignored him, but Nagel made a polite gesture and doffed his corduroy cap.

The hotelkeeper turned to him and said: “That’s a man we call The Midget. He’s not quite right in the head, but I feel sorry for him; he’s a good fellow.”

Nothing further was said about The Midget.

“A few days ago I saw something in the papers about a man who was found dead in the woods somewhere around here,” Nagel said suddenly. “What kind of a man was he – Karlsen, I think his name was. Did he come from here?”

“Yes,” said the hotelkeeper. “His mother was a leech-healer. You can see her house from here – the one with the red tiles. He had only come home for the holidays and then ended his life while he was at it. It was especially tragic since he was a talented boy, and about to be ordained. The whole thing is very strange. Since the arteries on both wrists were severed, it could hardly have been an accident, could it? And now they’ve found the knife – a small penknife with a white handle; the police found it late last night. The whole thing seems to point to some love affair.”

“That’s interesting. But is there really any question as to whether he committed suicide?”

“Everyone hopes the matter will be cleared up – I mean some people think that he may have been walking with the knife in his hand and stumbled so awkwardly that he cut both wrists at once. But that seems highly improbable. Nevertheless, he will be buried in consecrated ground. But I for one don’t believe he stumbled!”

“You say they didn’t find the knife until last night? But wasn’t it lying next to him?”

“No, it was lying several feet away. After using it he threw it into the woods; they found it quite by chance.”

“But why would he throw the knife away when he was lying there cut and bleeding? It certainly must have been clear to everyone that he had used a knife?”

“God knows what was in his mind, but, as I said, there is probably a woman mixed up in it somehow. It’s strange; the more I think about it, the more complicated it gets.”

“What makes you think that a woman is involved?”

“Several things. But I’d rather not go into it.”

“But don’t you think the fall could have been an accident? He was lying in such an awkward position – wasn’t he lying on his stomach with his face in the mud?”

“Yes, and he was covered with it. But maybe he arranged it that way on purpose to hide the final death agony. Who knows?”

“Did he leave a note of any sort?”

“He seems to have been – writing something, but apparently he was in the habit of making notes while taking his walks. Some people think that he might have been using the knife to sharpen his pencil when he stumbled and fell, and jabbed a hole in one wrist and then in the other – all in the same fall. But he did leave something in writing. He was clutching a piece of paper in his hand with the words: ‘Would that thy knife were as sharp as thy final no.'”

“What rubbish. Was the knife dull?”

“Yes…”

“Why didn’t he sharpen it first?”

“It wasn’t his knife.”

“Whose knife was it?”

The hotelkeeper hesitated for a moment: “It was Miss Kielland’s knife.”

“Miss Kielland’s knife?” repeated Nagel, and after a slight pause: ”Well, and who is Miss Kielland?”

“Dagny Kielland. She is the minister’s daughter.

“That’s very strange – very odd. Was the young man so madly in love with her?”

“He must have been. But they’re all mad about her. He wasn’t the only one.”

Nagel seemed to drift away, lost in his thoughts.

The hotelkeeper finally broke the silence by saying: “What I just told you is confidential, so I must ask you to…”

“I understand,” Nagel replied. “You don’t have to worry.”

When Nagel went down to lunch a while later, the hotelkeeper was already in the kitchen announcing that at last he had had a real talk with the man in yellow in Room 7. “He’s an agronomist, and he’s just returned from abroad. He says he’ll be here for several months. Hard to figure him out.”

From the Serpent’s Tail Classics edition of Mysteries, translated from the Norwegian by Gerry Bothmer © 1971 by Farrar, Straus & Giroux, Inc.

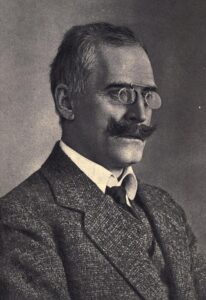

Knut Hamsun was born in Gudbrandsdalen in southern Norway in 1859, and grew up in poverty in Hamarøy, deep within the Arctic Circle. He is best known for the groundbreaking series of novels Hunger (1890), Mysteries (1892) and Pan (1894). He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1920 for Growth of the Soil. By the time of his death in 1952 he had fallen out of favour for having been a Nazi sympathiser, but has since been championed by influential writers from Karl Ove Knausgaard to Doris Lessing and Isaac Bashevis Singer, and the power and humanity of his greatest works is undiminished. Mysteries is published in paperback and eBook by Serpent’s Tail Classics, with an introduction by James Wood.

Read more

serpentstail

@serpentstail