My Mauretania

by Julia DarlingMy name is Horace Flemming.

A girl with a kind, beaky nose and a leather notepad burst into my room this morning and said she wanted to know about ships. She’d found out about me in the library. I was in an old newspaper, she said. The man who made the model ships.

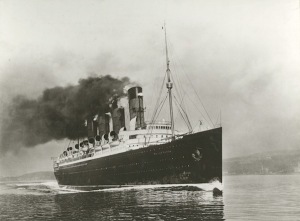

That was my job. While the shipyards bellowed and screamed, and the tiny workers were dwarfed by the giant ships that launched themselves into the Tyne, I worked in a little room at the back of the yard, making a miniature version of each ship. The models were exhibited in glass boxes in the offices and admired by visitors.

The girl got me all stirred up. Nearly missed my dinner.

Dinner is not something to miss in Cresthaven House, which is a council home for the elderly and often bewildered with thin doors, cheap windows, and pink and blue armchairs arranged in open-mouthed circles, and over-perfumed dead flower heads in glass bowls.

There’s thirty-eight women in here and two men. The other man is so old, he’s like a bundle of twigs tied together with string with a shirt on top.

Half of the people in here are nutters. They stare at the bright television screens, half asleep, snoring, falling into each other’s laps. Sometimes I think we’re all in a birdcage, with our heads under our wings. Old maggoty birds. I didn’t want to talk about the ships. I would have preferred telling the girl about pigeons, which interest me. About the crees up on the hill and the way I used to throw the birds up into the sky as if they were grey stones. About their bright beady eyes looking at me in the dark, as if they knew everything. But she wanted to know about ships, even though her eyes were astute like a pigeons, and the way she flapped was birdy too. She was wearing a long mackintosh.

‘You must be a very clever man,’ she said with enthusiasm.

‘Oh yes, I boasted, ‘I made a model of the Mauretania with my bare hands, a few chisels, tiny brass nails, wire etcetera.’ When I said ‘etcetera’ I spat.

I showed her my liver spotted rusty fingers, shaking and quivering. They can hardly hold a spoon now.

‘Gosh,’ she murmured.

‘I had a workshop at the yard,’ I went on. ‘A little cubby hole, a kettle and a radio, and a paraffin heater. They left me alone. Every ship had a model but the Mauretania was the biggest.

‘Mother had eight daughters, and me. The only son. My hands were like a girl’s. Soft and small, thin and white. Like calf hide.’ I touched the girl’s cheek with my stiff hand and she frowned, then laughed.

‘Always on my own,’ I said thinking out loud. ‘Always a boy in a nest of women.’ I stopped. ‘Don’t get me wrong,’ I said, ‘I like women. I made other models, The Monarch, The British Princess. They took years. Never got much credit.’

I lit up a cigarette and the small room filled with smoke. She waited for me to speak, her head on one side.

‘Tiny doors,’ I told her, ‘weeny little door handles, baby anchors, and shackles the size of a pin.’

‘Go on,’ she said.

‘The Mauretania was the last model I made.’ I paused and sucked in the blue smoke.

I was working on the model one day when I noticed that one of the hatches was open. I leant down to look inside, and that’s when I saw the woman’s face, size of a drawing pin, looking up at me.”

Even I was surprised by the tears. They started rolling down my nose uncontrollably. That’s what it’s like being old and bewildered. You never know which emotion will surface from the depths. They bubble up, like gas in a swamp.

‘But I had a bit of trouble,’ I gulped.

‘I know,’ she said, and rummaged about for a handkerchief. I blew my rubbery old nose.

She looked at me carefully. Then walked to the window and picked up a photograph of me and my sister Ettie from the mantelpiece.

‘Is that you?’ she asked.

I nodded. In the photograph I am looking shyly at the ground. I was never a good mixer. I talked into the folds of her mackintosh. It listened to me intently.

‘You see, I was working on the model one day when I noticed that one of the hatches was open, and I knew that I had stuck it down the day before. I leant down to look inside, and that’s when I saw the woman’s face, size of a drawing pin, looking up at me from the hollow room of the ship.

‘Good heavens!’ the girl said.

‘The face was brown and drowsy, as if she had just woken up. I shut the door and carried on working. It wasn’t the kind of thing I would tell the other men, that I’d seen a fairy girl. Also I was wondering if my eyes were going.’

‘Come on,’ snorted the girl in a mackintosh. ‘You’re having me on!’

I blew my nose. The tea trolley came tinkling along the corridor. Lynne, the care assistant, gave me a cup of weak tea in a colourless plastic beaker. The girl drank silently from a china cup.

‘There were footprints on my drawings too,’ I told her. ‘Shadows crossing my palm. Sometimes threads untangled in the night. Door handles got polished.’

She chuckled. I chuckled with her, even though I didn’t find it that funny. ‘I didn’t mind it at first,’ I told her.

She took another sip of tea and shook her head. ‘So what went wrong?’ she said as if she already knew.

‘What do you mean?’ I said.

‘You were in the newspapers,’ she said gently. I panicked. What else did she know?

‘Didn’t you launch the model of the Mauretania? A girl saw it. She was wandering down by the yards. Saw a miniature ship bobbing about in between tankers.’

I struggled with something in the marshes of my memory, and then I saw her. A girl in a red dress, holding out her arms, lit by golden lights. I nodded at the girl.

‘Guess what?’ she whispered. ‘That girl was my mother. She was playing by the river, when a glittering thing came cruising towards her. She couldn’t believe it. She said it was gigantic and tiny all at the same time. Too big for a toy. Too small for a boat. She leant towards it, to try and touch it and fell in the river. She nearly drowned. A passing man from the yard saw her and rescued her.’

I stared at her feathery face peering at me.

‘That was me,’ I stuttered. The little wet girl, face down in the dirty water. The Mauretania gliding past. The metallic taste of the water.

Her eyes blinking open. When I did speak my voice was squeaky and shrill. ‘She ran away. But I knew she’d seen. That’s why I confessed.’

‘She told me the story. I wondered if it was really true. Then I went to the library and there was the story of the model maker who launched the model of the Mauritania into the Tyne.’

I stared at her. I could taste iron. I could hear women’s voices cheering and singing from somewhere in the distance.

‘She died a few months ago. My mother. She was sitting on a jetty looking out to sea when a large wave scooped her up and swallowed her. Can you believe it? She got drowned after all.’

I never could explain what I did to the police. As far as they were concerned I had stolen shipyard property. I wasn’t going to admit what really happened. It was the best ship I ever made.”

Now the girl’s eyes filled with tears. I passed her the handkerchief. For a while we both stood there, blubbing. It seemed to late to ask her what her name was.

The dinner bell was ringing downstairs. We got up together and started the long journey downstairs with me hanging on to the zimmer. So slow. I could smell mashed potato and soup, but I couldn’t stop thinking of ships. The girl was behind me. Her coat made a swishing sound as she came along the corridor. She was still sniffing.

We got into the lift together.

The girl said, ‘Why did you do it? I mean, it must have taken years to make. Why did you launch it?’

‘After the real Mauretania was launched my finished model was displayed with all the other models. It was beautiful. The best model ship I had ever made. I thought I might win a prize or something… it’s a funny feeling when you finish a model. It’s as if a piece of yourself has slipped away.’

She nodded. The lift door opened, but we didn’t get out. We just stood there.

‘The night I finished building my Mauretania I couldn’t sleep. I lay in bed all alone, because I never married. I lived with my sister Ettie. Spent all my life in a spare room. I lay there with my eyes wide open, planning my retirement. I was worried about it you know. I wasn’t sure what was going to happen. Then I heard a scraping at the window. I got up to see what it was, and there was a fierce miniature sailor woman looking up at me from the windowsill with an anchor in her hand.

‘I’m after you, she yelled, although it would only have sounded like a squeak. We want to go to sea!

‘No, of course I can’t, I said. It’s out of the question. I went back to bed and pulled the sheets up over my ears.

‘But that was just the beginning.

‘Night after night the sailor girls came. They bit my lovely hands all over with their sharp teeth, so that I couldn’t even lift a teapot, and they scattered brass tacks in the bed linen and sprinkled wood dust in my eyes. After a few weeks I was a wreck. Every single night for two months, they came. I was unrecognisable. People thought I had a disease. The doctor gave me tranquillisers and I started to get a reputation. Crazy Horace, spent too long on his own. Perhaps I had.’

The girl was making a cooing sound. ‘What do you think?’ I gabbled.

She shrugged.

‘I wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t for you,’ she said, and squeezed my hand.

‘I never could explain what I did to the police. As far as they were concerned I had stolen shipyard property. I wasn’t going to admit what really happened. It was the best ship I ever made. I smashed the glass case and lifted it out. It was very heavy, and full of whispers. I took it down to the river after dark and pushed it into the water. You know, as I did it I realised I’d always wanted to launch the ships I made. I felt like a child again, with a new toy. Then I heard the crew of tiny sailor girls cheering and laughing, and all the lights went on. It glittered. It just looked magnificent. I clapped my hands and that’s when I saw the child on the quayside, her face all lit up like mine, leaning towards the ship, reaching out as if it was Christmas. I knew she would fall. The river was waiting for her.

‘I watched her slip into the water. For a second I wavered. I admit it. After I’d got her out of the water my Mauretania had gone. The child gawped at me. Her hair was matted with oil and her face streaked with mud. She was just like a skinny dog. I held her shoulders like this, for a moment. It was dark, there was no one there.’

I had a coughing fit. The girl handed back the damp handkerchief. ‘Then I let her go.’

‘Yes, you did,’ the girl said.

‘They called me a crazy thief. They didn’t even give me a golden watch on a chain. Put me on medication. Largactil.’

She squeezed my arm. The lift was going back up again. I cleared my throat. ‘I went to the pigeon lofts after that. Kept out of everyone’s way. I made the pigeons little chairs and ornamental mirrors to lighten up the darkness of the boxes,’ I beamed.

The lift doors shunted open again.

‘Thanks,’ she said, ‘I’ll let you have your dinner Horace. Perhaps I could come and see you again?’

We shook hands.

I saw her flying off down the path in her grey mackintosh, my story caught under her wings. I sat ploughing my way through a mountain of mashed potato, and for a moment it all made sense, and for the first time I let myself wonder how far they’d got in my Mauretania, that part of me that had slipped away, singing and cheering, out of the mouth of the oily Tyne.

Julia Darling (1956–2005) was a novelist, poet and playwright. Her published work includes a collection of short stories, Bloodlines (Panurge); two novels, Crocodile Soup and The Taxi Driver’s Daughter (Penguin); and two collections of poetry, Sudden Collapses in Public Places and Apology for Absence (Arc). With Cynthia Fuller, she edited The Poetry Cure (Bloodaxe), a collection of poetry about health. Her work for theatre and radio was collected in Eating the Elephant and Other Plays (New Writing North). She was awarded a £60,000 Northern Rock Foundation Writer’s Award in 2003, and was a fellow at the School of English Language and Linguistics at the University of Newcastle upon Tyne. Pearl, the definitive collection of her short fiction, is out now in paperback from Mayfly Press.

Julia Darling (1956–2005) was a novelist, poet and playwright. Her published work includes a collection of short stories, Bloodlines (Panurge); two novels, Crocodile Soup and The Taxi Driver’s Daughter (Penguin); and two collections of poetry, Sudden Collapses in Public Places and Apology for Absence (Arc). With Cynthia Fuller, she edited The Poetry Cure (Bloodaxe), a collection of poetry about health. Her work for theatre and radio was collected in Eating the Elephant and Other Plays (New Writing North). She was awarded a £60,000 Northern Rock Foundation Writer’s Award in 2003, and was a fellow at the School of English Language and Linguistics at the University of Newcastle upon Tyne. Pearl, the definitive collection of her short fiction, is out now in paperback from Mayfly Press.

Read more

juliadarling.co.uk

@MayflyPress

@NewWritingNorth