Writing in the #MeToo era

by Sarah HenstraShocking revelations, a barrage of headlines, rising public outrage, hashtag activism, and… fiction. My novel The Red Word has been launched at the height of the #MeToo movement, and from its first days on the market it’s been praised for being ‘timely’. How does it feel to have written such a timely novel? How has #MeToo shaped the way I wrote this story? What made me decide to jump into such a politically hot topic?

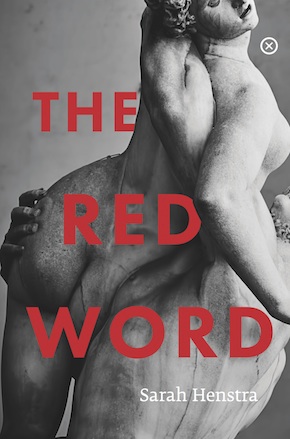

Such questions from interviewers shouldn’t be surprising to me in the least. The Red Word is about a group of feminist students at a US university in the mid-1990s who stage a public scandal at a prominent fraternity house to expose its toxic ‘bros before hos’ rape culture. Journalists looking to review the book or speak to me about its themes need to find its ‘hook’ – to highlight whatever aspect of the story will best connect with current events and the social concerns of the moment. So a focus on #MeToo-related themes makes perfect sense.

And yet, the claim of timeliness for The Red Word causes me to feel a bit fraudulent. Describing a book as timely makes it sound like one day you take a look at what’s blowing up Twitter and say, “Oh yeah, gonna sit down a sec and write a novel about that.” And that is not really how fiction-writing works. Even if by some miracle you write it really fast (which I did not), and get it perfect right out of the gate (which I did not), novels take forever to come into print via traditional publishers – especially if it’s your first one or if you wrote it for a new market (which I did).

I started The Red Word way back in 2013. Editing and production took even longer than usual – we wanted to coordinate Canadian/US publication dates, get the right blurbs on the jacket, and so on – and I suppose the long wait worked in the book’s favour, as more and more people have meanwhile become interested in some of the issues it grapples with, such as sexual harassment and violence. That topic was current five years ago when I started writing, but now it’s so buzzworthy that my book is trumpeted as timely.

Though rape culture is every bit as big a problem at universities as everywhere else, I didn’t begin with a conscious agenda to comment on it. I was more generally curious about the clash between ideas and real life that can happen to university students when they begin to learn about ‘big ideas’ in the classroom – those world-changing philosophies and political ideologies that inspire dissatisfaction with the status quo – and at the same time are let loose from their parents’ and teachers’ supervision for the first time and tend to go a bit wild. Pitting the radical feminist sisters against the fraternity brothers was a way for me to explore this ideas-vs-practice tension in real time, in the dramatic space of the story.

It’s not that I wished to shy away from or smooth over the thorny issues with which my characters struggled. Through the usual rounds of revisions I worked with my editors (particularly Amy Hundley in the US) to make the novel’s exploration of political and ethical themes more explicit without becoming preachy or didactic.

In the 1990s on college campuses (as elsewhere), the dice were so loaded against the survivors of sexual violence that justice seemed an impossible prospect.”

For a ‘timely’ story about campus rape culture, though, The Red Word doesn’t make a straightforward argument about that issue so much as ask a bunch of difficult, potentially disturbing questions about it. The book tackles complicated subject matter, so I felt it warranted a complicated treatment. My decision to have the feminist students stage their attack on the fraternity the way they do (using ethically dubious methods) arose from two separate impulses I felt as a writer: one having to do with what story I was telling and the other with how to tell the story. In the 1990s on college campuses (as elsewhere), the dice were so loaded against the survivors of sexual violence that justice seemed an impossible prospect. The young women in the novel are so frustrated with inequality, so sick of recording and reacting to the misdeeds of the frat boys without seeing any real changes, that they believe this is the only way forward, and they’re convinced – for a while, at least – that the ends will justify the means.

In terms of the story’s structure, I sought a scenario that would leave open the maximum number of possible resolutions in order to allow readers to remain curious and to consider a wide variety of perspectives and points of view. After all, it’s the unexpected consequences of the plot – those surprise moments when events blow up way past the characters’ intentions – that keep us reading.

I’ve always liked Susan Sontag’s assertion (in her 2004 lecture on South African Novel laureate Nadine Gordimer) that good novelists are moral agents precisely because the stories they tell don’t moralise but instead “enlarge and complicate – and, therefore, improve – our sympathies. They educate our capacity for moral judgment.” It definitely took The Red Word longer to find a publisher because of its lack of a redemptive or hopeful resolution, though. “What is the takeaway here for feminism?” one editor asked me. Luckily, the publishers who strongly connected with it (including Lisa Coen and Sarah Davis-Goff at Tramp) loved it for precisely its refusal to come down cleanly on one side of the conflict.

The claim of timeliness might also underplay some of The Red Word’s historical aspects – the fact that it takes place twenty-five years in the past. I’ve been a feminist scholar for three decades now, so I’ve seen first-hand a lot of the debates and changes in feminist thinking. The argument of feminism is breathtakingly simple: women deserve to be taken as seriously as men. Most people can get on board with that idea, right? But how to go about transforming the political, economic and cultural structures that prevent the idea from being a reality – that’s where feminism necessarily explodes into a kaleidoscope of analyses, debates, proposals, programmes, curricula, campaigns, and so on. It was a lot of fun for me to recreate some of the discussions I’ve had over the years with other feminists, and to develop a cast of characters who are actively trying out these disparate ideas, trying to put them into practice (for better and for worse!).

The 1990s was a time when third-wave feminism took academia by storm. Identity politics, feminist critical theory in the classroom, and grass-roots student activism campaigns made college a heady and exciting place for young women who found their professors and fellow students engaging in very different conversations than they’d been exposed to at home or in high school. I suspect going off to college feels like this in every era – like discovering a brand-new world – but the 1990s was my undergraduate era, and part of the pleasure for me in writing this story was to (re)create that historical moment through memory and period detail.

As both an English professor and a writer I’m deeply invested in and curious about young people, their theatres of study and learning, and the power structures (and imbalances) that shape those theatres. To explore these subjects in The Red Word I drew on memory but also my everyday ‘insider’ experiences as a university teacher. A lot has changed since my undergrad years: at least in Toronto where I teach the student body is more diverse and more likely to live at home with parents, commute to school, and work off-campus part-time to pay tuition. But universities are still pretty elite places, and a lot of effort still goes into covering up scandals and maintaining a pristine public image.

I may not have set out to write a #MeToo novel. But now that The Red Word is alive in the world, being read and discussed in the contexts of rape culture, consent and social change, I’m proud to have contributed something meaningful to the conversation. Seeing my work reach beyond my private, solitary experience of writing to take on a wider significance for readers has given me an amazing sense of coming full circle, of homecoming, in my journey as a writer.

Sarah Henstra is the author of the YA novels Mad Miss Mimic and We Contain Multitudes, and a professor of English at Ryerson University in Toronto, ehere she teaches courses in Fairy Tales & Fantasies, Gothic Horror, Creative Writing and Psychoanalysis & Fiction. Winner of Canada’s Governor General’s Literary Award, The Red Word is out now in paperback from Tramp Press.

Sarah Henstra is the author of the YA novels Mad Miss Mimic and We Contain Multitudes, and a professor of English at Ryerson University in Toronto, ehere she teaches courses in Fairy Tales & Fantasies, Gothic Horror, Creative Writing and Psychoanalysis & Fiction. Winner of Canada’s Governor General’s Literary Award, The Red Word is out now in paperback from Tramp Press.

Read more

Buy from amazon.co.uk

sarahhenstra.com

@TrampPress

Author portrait © Paola Scattolon