Other Africas

by Michela Wrong

“A first-class legal thriller, written with narrative verve and a reporter’s eye for detail.” Financial Times

Most first-time visitors’ images of Africa are shaped by the safari experience, which is defined by its artificiality. Camping hundreds of miles from the nearest office block or high street, they learn every detail of an elephant’s sex life but catch only brief glimpses of how the locals live. Western reporters, in contrast, are drawn to urban centres, because it’s there that the raw material upon which they depend – interviews with politicians, businessmen and activists – is usually to be found.

Over the years, every journalist draws up a mental list of favourite African destinations, places where they can work with startling ease, where history and culture enrich the experience and interactions with residents feel unforced. These are often middle-sized market towns rather than exhausting megacities, places where everyone knows everyone, you can stroll from one appointment to another and amble back to your guesthouse at night without fear of mugging.

Asmara, Eritrea

Eritrea’s image in the West has taken a battering as thousands of youngsters fleeing military service risk the high seas. But discerning travellers still regard Asmara as Africa’s most elegant capital. Eritrea was Italy’s first colony, meant to be Rome’s jumping-off point into the continent. Perched on the Hamasien plateau, far above cloud cover, the city served as an experimental petri dish for Italian Mussolini’s Fascist architects and remains a well-preserved tribute to 1930s Modernism. The marble-lined cinemas ooze Cinecittà glamour, the zinc bars hiss with the sound of Gaggia machines pumping out a stream of espressos and cappuccinos. No wonder a local group is applying to UNESCO for World Heritage status. Any resemblance between Asmara and the fictional city of Lira in Borderlines is purely intentional: the opportunity was too good to miss.

Hargeysa, Somaliland

The capital of the self-declared republic of Somaliland is the kind of place where donkeys meander through traffic and drivers are advised to check under bonnets for sleeping goats before starting their engines. Much of the city was flattened in 1988 in a bombing campaign ordered by long-term Somali President Siad Barre, and today’s city is dotted with sculptures and memorials poignantly dedicated to the liberation struggle. Somaliland has been spared the clan violence that has blitzed Somalia proper, and members of the diaspora are opening cyber cafes and gyms. Al Shabaab may have sown terror in what is dismissively known as ‘the south’, but here security is so good, money traders sell stacks of local currency by the roadside. The teashops do a roaring trade, as do the kiosks selling the stimulant khat, instantly recognisable by the mounds of leaves discarded by customers before getting down to the serious job of chewing.

Jinja, Uganda

Strategically positioned on the banks of Lake Victoria, on the main highway to neighbouring Kenya, Uganda’s industrial heartland fell into a state of genteel decline during Idi Amin’s time in office. When the self-styled Last King of Scotland gave the country’s Asian community just 90 days to leave in 1972, their businesses and properties were nationalised or left to the squatters. The pastel-coloured colonial villas are now being renovated by returning Asian owners, invited back by President Yoweri Museveni. Jinja’s sugar, beer, steel and palm oil factories are humming and there’s a strong tourism trade. The Source of the Nile, where Mahatma Gandhi’s ashes were scattered, is one draw; the headwaters themselves are popular with white-water rafters. But be warned: there’s no point asking directions for the famed Bujagali Falls: the construction of the Bujagali Dam in 2011 submerged them.

Nakuru, Kenya

Buzzing with boda boda motorbike taxis and boasting Kenya’s first free, citywide Wi-Fi network (Bilawaya), this Rift Valley market town has known its share of political troubles. It was here, after the 2007/8 elections, that the Mungiki, a mafia-cum-militia, sought revenge for the cleansing of Kikuyu farmers by the Kalenjin, attacking the ethnic communities employed on the local flower farms. The Kenyan army helped end those killings, but inter-communal distrust remains high and Nakuru, whose population has mushroomed in recent years, often feels tense and twitchy. Any undercurrents usually go unnoticed by Western tourists headed for one of Kenya’s smallest but best-value safari parks. The Lake Nakuru National Park hosts one of the world’s biggest populations of flamingo, a stinky, honking, pink multitude drawn by the algae that breed in the soda lake.

Arusha, Tanzania

Arusha, Tanzania

Arusha is a mecca for sponsored walkers bent on scaling Kilimanjaro, as well as tourists applying for permits for northern Tanzania’s game parks, including the legendary Ngorogoro crater. It also happens to be the headquarters of the East African Community, working on the laborious task of integrating the region’s economies. Local rents rose when the town was chosen as a base for the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, established to try the military leaders and politicians who organised that country’s 1994 genocide. Judges, lawyers and journalists flooded in. The court winds up in December, but there’s another reason to go: the jacaranda trees lining Arusha’s streets. They bloom in October, turning the town into a haze of purple. It’s one of East Africa’s most beautiful sights, all the more precious for its transience.

Durban, South Africa

The greenest of South African cities, Durban sits in a sea of billowing sugar cane and is fringed by beaches popular with surfers, despite the famously aggressive sharks. The young Gandhi cut his legal and political teeth here. It’s also President Jacob Zuma’s home turf, so the city has more than its fair share of infrastructural white elephants: the airport is one, a stunning sports stadium built for the 2010 World Cup another. Full of museums and galleries, the centre turns into a dark and threatening Gotham City at night. It’s best then to head for the bars and restaurants of Morningside, where the beautiful people hang out: don’t believe those who tell you puritanical Zulus save their party-going for ‘Jozi’ – Johannesburg. Durban’s townships, which sprawl across the hills overlooking the city, are also surprisingly cheerful spots: dotted with mango trees, bursting with flowers and softened by lawn, they are undergoing a major government upgrade.

Dakar, Senegal

Prosperous African-Americans head for Dakar bent on reconnecting with their roots. Île de Gorée, a short ferry ride from the port, was the last glimpse many of their forefathers caught of Africa as the slave traders pulled them from cellars and shipped them off to the New World. Today it’s hard to reconcile this picturesque island with past horrors. But the mainland has a different appeal: you’re in Francophone Africa and everything – from the Beaujolais Nouveau whose arrival is still considered an event worth celebrating, to the cuisine and nightlife – feels different. The narrow alleys, shops and markets all encourage wandering, but don’t make the mistake of coming to a halt: Senegalese traders pride themselves on their relentlessness. While Senegal is one of the continent’s most stable democracies, it still boasts the odd monarchical folly: witness the monstrous bronze statue – Africa’s biggest – perched on a hill overlooking Dakar, a project dear to former President Abdoulaye Wade’s heart.

Bukavu, Democratic Republic of Congo

Bukavu, which curls round the southern tip of Lake Kivu, was once known as Costermansville, a popular holiday destination for Belgian settlers. Despite having survived Biblical refugee flows from neighbouring Rwanda and lived through a series of militia takeovers, it still retains the relaxed feel of a Swiss spa town. The dilapidated colonial villas and hotels – the Orchid Hotel is the one everyone tries to book – look across the blue waters of what is said to be a bewitched lake in one direction, the banana-planted green hills of Congo in the other. The local university has fallen on hard times, just like every public institution in DRC, but Panzi Hospital has turned its director, gynaecologist Denis Mukwege, who was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize, into an international hero. He treats the victims of child marriage and gang rape, suturing the fistulas that made them public outcasts.

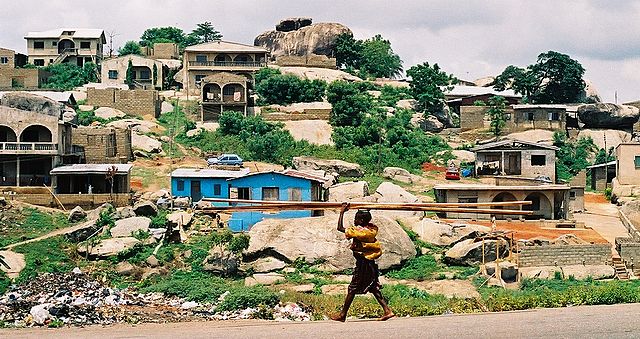

Abeokuta, Nigeria

Abeokuta, Nigeria

An hour and forty minutes’ drive north of Lagos, Abeokuta is circled by the winding Ogun River and dominated by a sacred giant rock, disfigured by an ugly (and usually out-of-order) lift. The home town of both feisty Nobel Prize winner Wole Soyinka and former President Olesegun Obansanjo, it’s famous for its indigo cloth, made using simple hand-printing techniques unchanged for centuries. The town’s most recent claim to fame is the Ake International Book Festival, staged in November and organised by the irrepressible Lola Shoneyin, author of The Secret Lives of Baba Segi’s Wives. The festival has started attracting writers, thinkers and poets from across the continent. It seems only fitting for a country which remains the intellectual and creative powerhouse of Africa.

Djibouti City, Djibouti

Sweltering on the Red Sea, the only landmark in a rolling expanse of sand and scrub, Djibouti was for decades best known for the shaven-headed Foreign Legionnaires who trained here, making a virtue of the harsh environment. Nowadays the uniforms are more varied. From Camp Lemonier, the only permanent US base in Africa, American soldiers monitor the spread of Islamic fundamentalism, dispatching drones to Somalia and Yemen. French Mirage jets take off from the airport, while Japanese and German troops track Somali piracy. The tiny historic centre has a certain colonial charm but the state-of-the-art port is the country’s true raison d’être, the Horn of Africa’s main point of entry and aortic valve. The waterfront comes to life when the cool of night descends, and the hotels buzz with parties and wedding celebrations.

Michela Wrong has worked as a foreign correspondent covering events across the African continent for Reuters, the BBC and the Financial Times. Her first book, In the Footsteps of Mr Kurtz (2000), won the PEN James Sterne Prize for non-fiction. I Didn’t Do It for You (2005) built upon her shocking experiences in Eritrea. The thriller Borderlines, her first novel, is out now from Fourth Estate. Read more.

Michela Wrong has worked as a foreign correspondent covering events across the African continent for Reuters, the BBC and the Financial Times. Her first book, In the Footsteps of Mr Kurtz (2000), won the PEN James Sterne Prize for non-fiction. I Didn’t Do It for You (2005) built upon her shocking experiences in Eritrea. The thriller Borderlines, her first novel, is out now from Fourth Estate. Read more.

michelawrong.com

@michelawrong

Author portrait © Kate Stanworth