Pictures behind the story

by Lara Thompson

“From its breathless opening pages, One Night, New York transports the reader to the glitter and the danger of old New York.” Erin Kelly

All photographs are packed with stories. They surround us, littering our screens and walls with narrative and memory. Time embalmed. But for each of us, some images are packed fuller than others. Alighting upon a particular combination of light and shade, colour and form, a person we love(d), a fleeting delight – our attention is piqued. We stop and stare. As a writer words are everything, but without the images they conjure language is nothing more than dead lines. Likewise, some images ignite storytelling. The ten photographs that follow (primarily taken in the early 1930s) lit me up when I saw them. Some stand alone, asking nothing more of the viewer than their gaze – their stories glowing on their surface, translation unnecessary. Others need context to hold them up – a scaffold of words. All of them informed my debut novel One Night, New York, whether as catalyst for the entire book, as character inspiration or as locations and experiences. Set in New York around the Winter solstice in 1932, a few days before Christmas, the book begins with two women waiting on top of the Empire State Building to kill a man who has done something terrible to them. It’s a thriller and a love story, a noir and a coming-of-age tale. It would not exist without these photographs. Over the years I have learnt that I cannot write without images – moving or still. These are the ones that still move me.

Click on images to enlarge and view in gallery

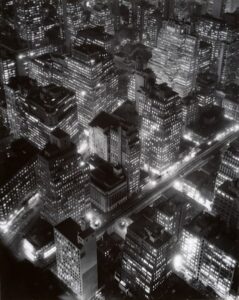

Nightview, New York by Berenice Abbott, 1932. Metropolitan Museum of Art” width=”215″ height=”270″>

Nightview, New York by Berenice Abbott, 1932. Metropolitan Museum of Art” width=”215″ height=”270″>

Nightview, New York by Berenice Abbott, 1932. Metropolitan Museum of Art

I owe so much to this image and its accompanying story. I even stole the comma in its title for my book. It’s a testament to the fact that sometimes an image, while beautiful on first glance, can become packed with meaning once accompanied by context. A few days before Christmas in 1932, Berenice Abbott, celebrated 20th-century American photographer, bribed a security guard and climbed to the top of the Empire State Building with her camera. Due to the necessary light conditions she only had fifteen minutes to get the exposure right. Beneath her the city is electrified. The image embodies a fantasy of New York – a thousand lit windows burning brighter than the stars. I couldn’t ignore the story of a woman standing on top of the tallest building in the world, capturing the city during one of the most exciting, traumatic and innovative periods in American history. Here Abbott was – not just at the epicentre of it all, but immortalising it. Crafting history with her camera.

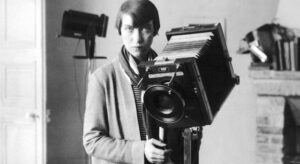

Berenice Abbott in Paris, 1928″ width=”300″ height=”164″>

Berenice Abbott in Paris, 1928″ width=”300″ height=”164″>

Berenice Abbott in Paris, 1928

After I’d seen Night Scene, New York and read Abbott’s story of the night she took the photo I did some more research. This was one of the first images I found. Abbott’s standing in what I assume is her live/work studio lightly touching a large-format camera. She stares resolutely at us. At first I was drawn in by her gaze – the sheer force of it. Then I saw how delicately she was resting her hand on the camera and realised how much it resembled an image of lovers. Like an old wedding photo, except here the camera on the tripod is the groom Abbott is very much in control of. The more I learnt, the more I was enamoured. Born in Ohio in 1898 as the century began, she moved to New York at 19 then boarded the SS Rochambeau to Paris in her mid-twenties, became Man Ray’s assistant, then Atget’s, and photographed everyone from Jean Cocteau to James Joyce. She was notoriously private. When a journalist once asked about her sexuality she said: “I am a photographer, not a lesbian.” After returning to New York and documenting the burgeoning city in her pioneering book Changing New York she became an experimental scientific photographer, inventing her own cameras and moving to a farmhouse in Maine. She loved to play ping-pong and died aged 93 as the century was drawing to a close in 1991. She was everything I love in a woman (and a character) – bold, fearless, creative, irreverent, frequently pissed off.

c. 1930. MoMA/Library of Congress” width=”193″ height=”250″>

c. 1930. MoMA/Library of Congress” width=”193″ height=”250″>

Margaret Bourke-White atop the Chrysler Building by Oscar Graubner, c. 1930. MoMA/Library of Congress

This is one of those images that holds it’s narrative on the surface – I mean look at it! Here’s Margaret Bourke-White, another of the 20th century’s great photographers, astride one of the Chrysler eagles with her camera. One more daring, courageous, inspirational woman shaping history, risking life for art.

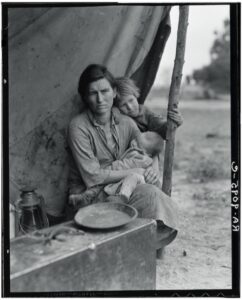

Migrant Mother by Dorothea Lange, 1936″ width=”209″ height=”260″>

Migrant Mother by Dorothea Lange, 1936″ width=”209″ height=”260″>

Migrant Mother by Dorothea Lange, 1936

A contemporary of Abbott and Bourke-White, Dorothea Lange changed the course of the lives of many poor sharecroppers and migrant labourers with just six images of a mother and her children taken on one day in 1936. The close-up Migrant Mother is the most famous of these, but I also like this medium shot. The frown lines, the child’s head lightly resting on the mother’s shoulder, the empty plate in the foreground. It tugs at the heartstrings in exactly the way Lange intended. The woman, later revealed to be Florence Owens Thompson, one of the many victims of the Great Depression, had been feeding her family frozen vegetables and dead birds the children were instructed to catch and kill. Once the federal authorities saw the pictures, they finally rushed much-needed help to the camp. This is the hell my protagonist Frances is escaping when she boards a train in Kansas and runs to the city. It is the inverse of Abbott’s night scene; two simultaneous sides of the American Dream I was eager to explore.

Metropolitan Museum of Art” width=”190″ height=”250″>

Metropolitan Museum of Art” width=”190″ height=”250″>

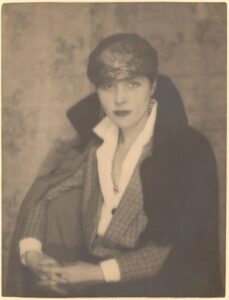

Portrait of Djuna Barnes by Berenice Abbott, 1925. Metropolitan Museum of Art

Abbott took this photograph of her friend and occasional patron Djuna Barnes, an artist, journalist, poet and playwright, in 1925. Barnes first lived in Greenwich Village in the teens and twenties and along with Abbott, Edmund Wilson and Guido Bruno, immortalised the area as a place of Bohemian artistic excess and ardent sexual experimentation. The sections of my book set in the Village would have been far less colourful, and the character’s outfits far less extravagant, had I not happened across this image of Djuna, sparkly turban and all.

US National Archives” width=”250″ height=”195″>

US National Archives” width=”250″ height=”195″>

The Harlem Hellfighters, 1918 (photographer unknown). US National Archives

To my great shame, I didn’t know Black GI’s fought in WW1 before I saw this photograph of the Harlem Hellfighters. The 369th Infantry regiment was a group of Black and Puerto-Rican soldiers from Harlem who were involved in some of the most notorious instances of hand-to-hand combat in the trenches. Initially derided by their fellow American soldiers and placed on cleaning duty, once in France they quickly become renowned for their bravery and lethal skill. Their fearlessness in battle led to the French nicknaming them The Men of Bronze and a number of the jazz-playing troop were awarded the Croix de Guerre – one of the highest French honours. On their return to the US they were momentarily applauded with parades, then swiftly, purposefully, forgotten. A hundred years later, it still amazes me how a country like America, built and protected by immigrants, still fails to treat their own Black citizens with the respect and honour they deserve. With his quiet, damaged bravery, my jazz-playing ex-serviceman Ben embodies the spirit of the Hellfighters.

LIFE Picture Collection” width=”198″ height=”250″>

LIFE Picture Collection” width=”198″ height=”250″>

Billie Holiday singing at Cafe Society by Gjon Mili, 1947. LIFE Picture Collection

My Dad loved Billie. He died just before I began writing my book. I missed him blasting out the jazz so I put in a brief glimpse of her. One of the joys of being a writer is the way you can bring people back to life for the briefest of moments. Their love(s), resurrected. So here’s Billie in Cafe Society, one of the first integrated clubs in NYC – smooth and soulful in her youth, gravelly and heartbroken as the drink and drugs overtook her. Always astounding. When she died Frank O’Hara ended his grief-stricken poem ‘The Day Lady Died’ with this:

and I am sweating a lot by now and thinking of

leaning on the john door in the 5 SPOT

while she whispered a song along the keyboard

to Mal Waldron and everyone and I stopped breathing

Automat, 977 8th Avenue, Manhattan by Berenice Abbott, 1936. Metropolitan Museum of Art” width=”240″ height=”190″>

Automat, 977 8th Avenue, Manhattan by Berenice Abbott, 1936. Metropolitan Museum of Art” width=”240″ height=”190″>

Automat, 977 8th Avenue, Manhattan by Berenice Abbott, 1936. Metropolitan Museum of Art

Pies. We all love pies, right? I used a lot of Abbott’s photography as source material for some of the locations in One Night. This one shows a man selecting a pie from one of the little glass cabinets in an Automat. I would honestly love it if someone brought back these wonderful cafes. Pies and sandwiches, hot soup, coffee, all freshly prepared. You put a few nickels in the slot and the little door unlocks. No need to wait in line to pay. 1930s fast food. Heaven.

At Le Monocle by Brassaï, 1933. MoMA” width=”192″ height=”240″>

At Le Monocle by Brassaï, 1933. MoMA” width=”192″ height=”240″>

At Le Monocle by Brassaï, 1933. MoMA

Stylish, classy, in love or simply looking for a good time. Here are some of the patrons of Le Monocle – Paris’ infamous 1930s lesbian nightclub. Regardless of your sexuality, is there anything more alluring than a men’s dinner suit and heels? It is easy to assume that sexual fluidity and gender non-conformity are recent developments, but as these photographs illuminate that is very much not the case. If pushed I’d say my main character Frances is pansexual (not that she knows it), but for me the most interesting thing about her isn’t her sexuality. Writing her was an exercise in exploring what it might have been like to feel like this and journey from the dustbowl to the city of lights. Culture shock doesn’t quite cut it.

Their First Murder by Weegee, 1941. The Art Institute of Chicago” width=”240″ height=”190″>

Their First Murder by Weegee, 1941. The Art Institute of Chicago” width=”240″ height=”190″>

Their First Murder by Weegee, 1941. The Art Institute of Chicago

There are a couple of murders in One Night and this looks very much like the aftermath of one of them. The image has always haunted me. Weegee was the preeminent renegade press photographer of the thirties and forties. He set up a short-wave radio in his car so he could eavesdrop on police responding to calls and get to crime scenes before anyone else. Here he captures a group of children and the grieving relatives beside the body of a murdered racketeer. As the woman in the centre mourns, the kids laugh and jeer and scuffle. Private grief becomes public spectacle. Most of all it’s the little girl in the centre that gets to me – shoved forward, half-smiling, her eyes blackened by the sight of it all.

Lara Thompson teaches film at Middlesex University, and is the author of Film Light: Meaning and Emotion. Born in Cornwall, she now lives in London. One Night, New York, her first novel, was chosen from two hundred entries as the winner of the Virago/The Pool New Crime Writer Award, and is now published by Virago in hardback and eBook.

Lara Thompson teaches film at Middlesex University, and is the author of Film Light: Meaning and Emotion. Born in Cornwall, she now lives in London. One Night, New York, her first novel, was chosen from two hundred entries as the winner of the Virago/The Pool New Crime Writer Award, and is now published by Virago in hardback and eBook.

Read more

_lara.thompson

@ViragoBooks

Author portrait © Charlie Hopkinson