A Pox on this Plague!

by Christopher Wilson

“What the doctor ordered… a fiercely funny novel.” The Sunday Times

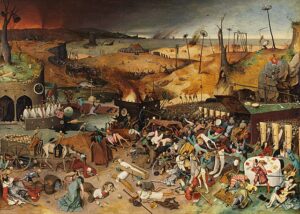

It’s 1349 in the Season of the Plague. The Black Death is scorching its path through England, leaving half the population dead in its wake. Folk suppose it’s a lethal miasma of foul airs. Or maybe it’s God’s punishment for human corruption. Or perhaps vagrants and money-lenders have been poisoning the wells. Medicine doesn’t help. The Church can’t intercede. Authority is impotent. It’s a perfect catastrophe.

Here is a tragedy of human suffering, and a comedy of human ignorance. This is a sophisticated God-fearing culture that entirely lacks the intellectual tools to see, understand or combat the miniscule bug that rips it apart.

A young monk, Brother Diggory, sets out to treat and cure the sick but – as an unwittingly carrier – takes death with him, from town to town, infecting and condemning whoever he meets. Not that that diminishes Diggory’s confidence or prevents him offering up his ten nuggets of wisdom for facing up to the Pandemic…

I. Look to the skies

For it is in the space between the Heavens and Earth that the Divine pass their portends and disclose to us their intentions. And there have been many warnings.

A column of fire had appeared above Avignon. It was the Comet Negra, and earthquakes and tempests followed in its wake. Jupiter was in conjunction with Saturn, which always bodes ill. A stinking smoke blew over from the island of Sicily. In the Low Countries it had rained scorpions, frogs and lizards. Red snow fell in Hungary. It was frozen blood. In Rouen a letter had dropped out of the sky. It had been delivered by an angel, having been written in Heaven, on vellum in red ink, in the hand of Jesus Christ Himself, saying that man must always observe the Sabbath, and scourge himself to repent of his sins.

II. Strain to discern the Divine Design

Since all things come from God, the Plague does too. Since God loves man, this sickness must come for our own good, perhaps to purify our souls, or to discipline us for our sins, or to test our faith in Him. So we must look for the good in this pestilence too, and see beyond the bad in it. This disease is for all mankind, since it treats all alike, high and low, man and woman, believer and heathen, young and old.

If the sick person is hot, they must be made cool. If they are wet with sweat, then make them dry. Taste their urine. A taint will disclose any imbalance of their humours. Then make a sound study of their shit.”

III. Confess and repent

In Hell a man weeps more tears than the water of all the oceans. It is a terrible things to die badly and unprepared, unconfessed and unrepentant, to face an eternity of torture and fire.

So every soul must think to their sins, scourge themselves to prove their contrition. There are many opportunities to secure our deserved suffering. For we each know what will pain us best.

IV. Observe how the Plague travels and see the company it keeps

The evidences and logics are that the pox is an atmospheric evil, carried by foul air. It blows from town to town. It crosses rivers and seas. It breezes over mountains. It cannot be seen. Only smelled. In the stenches of sickness, and the stink of decay.

Doctor Galen had shown that many plagues and distempers are caused by miasmas – clouds of poisoned, diseased air – from planetary actions, volcanoes, released from the ground in earthquakes, or brought down to Earth by comets.

Since the Plague blew up from the south, it makes sound sense to open only north-facing windows. And, being carried by the airs, we would be well advised to limit our labours and reduce the chance of poisoning by reducing the breaths we take.

See too the signs left by the lesser beasts. Fleas and lice flee the human afflicted, in search of safer terrain. Dead mice and rats appear in the wake of the pestilence, lumped and speckled black, as if they are poxed too.

V. Obey the proven rules of medicine

We are not alone in our task. For we have behind us the wisdom of the great doctors of all six ages of man, including Erasistratus, Oribasius, Hippocrates, Galen, Avicenna, Paul of Aegina and Hildegard of Bingen, to guide us in our task.

So we know this. If the sick person is hot, they must be made cool. If they are wet with sweat, then make them dry. Taste their urine. A taint will disclose any imbalance of their humours. Then make a sound study of their shit. Administer emetic and purgative so stomach and bowels are emptied of their sick yield. Much lettuce should be eaten, for it is cleansing and curative. Best bleed the patient to the point of causing faintness. Any boils and buboes must be lanced to drain away their poison. The incision should be made at the point of greatest pain, where the sickness is most intense.

VI. Fight smell by smell

Since the plague is caused by foul airs it must be countered by other, stronger smells – pleasant or foul – in a tournament of the airs. We can burn antimony, arsenic and sulphur, for they were known to purify the airs. Also, we might burn sweet-smelling woods such as cedar, myrtle, black birch, cherry, pine. Besides one may carry a posy of sweet-smelling flowers on one’s person, and sachets of strong-smelling herbs too – lavender, betony, sage, thyme, rue, comfrey, camomile.

There is power in stenches too. Bathing in urine might prove efficacious, for it is both beneficent to the skin and increasingly strong-scented with age. It might make further sense to smear one’s skin with excrement, for though the smell is rank it will wrestle and dispel the smell of the pox.

Since the plague is caused by foul airs it must be countered by other, stronger smells – pleasant or foul – in a tournament of the airs.”

VII. Cure by chicken and other remedies

Folk have sought a range of cures. It is said by some that if you pluck the nether end of a chicken, and then tie this living bird by its bald arse to your naked chest, the disease may flee your own body, into the unfortunate bird. Yet many physicians say this is just another fallacy concerning the prophylactic power of poultry.

It is claimed too that mothers’ milk is efficacious against the plague but, to achieve its full power, it must be gulped warm and fresh, straight from the breast.

Other folk have sought safety by eating crushed emeralds or ten-year old fermented treacle.

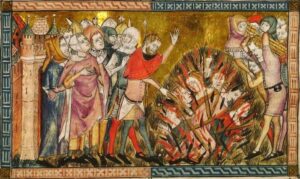

In Strasburg, Basel and Barcelona folk sought remedy by burning their Jews – but to no avail – until Pope Clement declared this an unchristian practice and a false cure.

VIII. It may profit you to kiss a Leper

Or lick him, for yet greater benefit. For it will signal to God Almighty your penitence and humility, and that you throw yourself open to His will, even to the extent of risking contracting leprosy yourself. This is to follow the example of Our Lord Jesus, who, it is told in the Gospel of Luke, reached out to touch lepers, and so cured ten on His way to Jerusalem, though only one ever returned to thank Him.

IX. Now the world is broke apart

We have all lost someone dear. Husbands, wives, sons, daughters are all in short supply. Near half of us are dead. We are like a book with half the pages torn out. We cannot tell the story we spoke before. Order is lost. Custom is ripped apart.

Villages are empty, abandoned. Doors swing loose, off their hinges. Fences are broke. Roofs are blown away. Crops are trampled, unharvested. Farm animals are gone feral.

The law is lost. Robbery is rife. Rogues rule the roads.

X. Yet everything in this world has a purpose

For it is the Lord’s purpose, though we may fail to grasp it at the time. So I thank God that all in his Dominion has an exact pattern and works to His exquisite plan.

And I think myself blessed, and a fortunate man. For, it is sure as fleas, if I had not been orphaned at birth, given away to a monastery, educated as a scribe and scholar, been killed by the pox, addressed by Death himself, given a sight of Hell, then raised to Heaven, and met the eternal radiance that is Our Lord, then been resurrected to the rude clamour of life, to be robbed by a one-legged man, sentenced to death for debating philosophy in Latin with a pig, escaped to live feral in the forest, been rescued by an epiphany of toads, married twice, and been twice bereaved, having first fathered a son, I should not be here playing my Hurdy-Gurdy in front of this crackling fire, nibbling roasted chestnuts, sipping mulled mead, with the golden haired Widow Caroline, thinking of our imminent bedtime.

Christopher Wilson has written several novels, including Gallimauf’s Gospel, Baa, Blueglass, Mischief, Fou, The Wurd, The Ballad of Lee Cotton, Nookie and The Zoo. His work has been translated into several languages, adapted for the stage, twice shortlisted for the Whitbread Fiction Prize, and shortlisted for the HWA Gold Crown. He lectured for ten years at Goldsmiths, London University, and has taught creative writing in prisons, at university and for the Arvon Foundation. He lives in North London. Hurdy Gurdy is published in hardback and eBook by Faber & Faber.

Christopher Wilson has written several novels, including Gallimauf’s Gospel, Baa, Blueglass, Mischief, Fou, The Wurd, The Ballad of Lee Cotton, Nookie and The Zoo. His work has been translated into several languages, adapted for the stage, twice shortlisted for the Whitbread Fiction Prize, and shortlisted for the HWA Gold Crown. He lectured for ten years at Goldsmiths, London University, and has taught creative writing in prisons, at university and for the Arvon Foundation. He lives in North London. Hurdy Gurdy is published in hardback and eBook by Faber & Faber.

Read more

mojo-books.com

@mojo_books

@FaberBooks

Author portrait © Sophia Kennedy-Wilson