Premontions

by Tove Jansson

“Jansson was a genius, a woman of profound wisdom and great artistry.” Philip Pullman

When I was young, a remarkable woman lived in the village where I grew up. Her name was Frida Andersson. Frida lived alone in a cottage by herself but she had a daughter and a grandchild in the city. Sometimes in summer they would come to visit, but as Frida grew more and more peculiar, they began to stay away.

The trouble was, Frida was haunted by a bad conscience. It became an obsession that no one could help her with. No matter what went wrong in the village, she thought it was her fault. When the village misfortunes were insufficient, she began to concern herself with everything she read in the newspaper, and then, of course, her anxiety became endless. Everything was her fault. It got worse and worse. In the end she just sat on her steps and cried.

I realize that this may be hard to believe, but no matter how foolish Frida’s misapprehensions became, they were a bitter reality for her. It was impossible to explain and convince, and severity had no effect at all. Now, years later, it occurs to me that perhaps we should have gone along with her delusions, but we didn’t. When no one agreed with her, she found comfort and confirmation in superstitious signs. A mirror is broken, two knives are crossed – there are portents and omens everywhere, if only you’re sufficiently open to them and to the guidance that comes from above.

You might suppose that Frida would have been an easy target for the village children, but it wasn’t like that at all. They were fascinated. Every time something bad happened in the world, the children all ran to Frida to hear the ghastly details. She had a powerful imagination and she could tell a terrific story.

I really believe that the children helped her a great deal, perhaps more than her portents.

I was seventeen at that time and of course I knew how the world worked, and almost everything else, plus it goes without saying that I liked to contradict and argue. It’s amazing that Frida liked me anyway.

On pleasant summer evenings we’d sit on her front steps and she’d tell me about what was going to happen. She’d warn me earnestly about the inevitable, the threat that comes steadily closer and eventually finds its catastrophe, which must always have a reason, a cause.

“And the cause, of course, is you,” I said, being sarcastic.

“Naturally,” Frida said and took my hand. “You know, on Friday morning a big white bird came and tapped its bill on the kitchen window three times. And what happened? There was an earthquake in California!”

I read intellectual books in those days and launched into an explanation of egocentricity, misdirected self-identification and God knows what else, and Frida looked at me in a friendly way and shook her head and said, “You’ll learn. But it will take time.”

I tried to brighten her up with the prospect of a summer visit by her daughter and granddaughter, but no, the child could fall in the well or drown in the marsh or get a fishbone caught in her throat and suffocate. Then I got tired and left.

If she didn’t believe in the town’s warnings she must nevertheless have had her own. There was no need for her to get hit in the head with a plain old piece of granite.”

That same summer, they were blasting for the new highway. It was a company from the city that was doing the work. They had a whistle they blew; then came the explosion. You got used to it.

The accident caused a sensation in the village. No one could understand why Frida couldn’t stay home when the whistle sounded. If she didn’t believe in the town’s warnings she must nevertheless have had her own. There was no need for her to get hit in the head with a plain old piece of granite.

I went to the hospital and they said I could talk to her for only a couple of minutes. There wasn’t a lot of her to see under all the bandages.

I held her hand and waited.

Finally she whispered, “What did I tell you? Now you have to believe me.”

“Of course, Frida,” I said. “You’re going to be fine. Now you just rest and don’t worry about a thing.”

Then, her voice clear and distinct, Frida said, “Exactly. You know what? For the first time in my life, I’m not worried at all. It feels wonderful. And now I’m going to sleep for a while. See you later.”

A whole mass of children were there for Frida’s funeral. They seemed expectant. But nothing remarkable happened – except later that evening there was a thunderstorm.

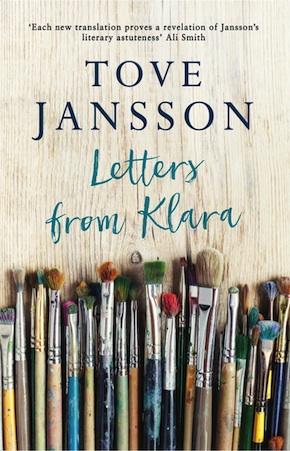

From the collection Letters from Clara and Other Stories, translated by Thomas Teal

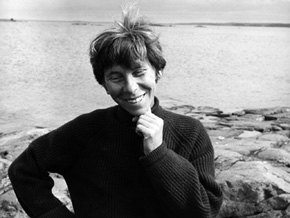

Tove Jansson (1914–2001) is best known as the creator of the Moomin stories, which were first published in English sixty years ago and remain in print today. In her 50s, she turned her attention to writing for adults, producing a dozen novels and story collections, including the classic, bestselling The Summer Book. Letters from Klara, her last collection of all-new stories, is out now in paperback and eBook from Sort of Books. Read more.

Tove Jansson (1914–2001) is best known as the creator of the Moomin stories, which were first published in English sixty years ago and remain in print today. In her 50s, she turned her attention to writing for adults, producing a dozen novels and story collections, including the classic, bestselling The Summer Book. Letters from Klara, her last collection of all-new stories, is out now in paperback and eBook from Sort of Books. Read more.

@SortofBooks

tovejansson.com

@ToveJansson1914

Thomas Teal has won the Rochester Best Translated Book Award and the Bernard Shaw Prize for Translation (twice) for his translations of Tove Jannson’s fiction. He lives in Massachussetts.