Reading and righting

by Ben AmbridgeBen Ambridge’s Psy-Q is a mind-bending miscellany of psychometric puzzles, quizzes, jokes and visual illusions that help us to understand and appreciate the workings – and occasional failings – of the human brain. Topics include whether eye colour denotes trustworthiness, if Rorschach’s famous inkblot tests really work, what your musical preferences say about you, how psychology might help solve the obesity crisis, and much more. Here, he investigates how the brain engages with letters on the page or screen.

Quick, what does this sign say?!

How cmoe it’s not taht hrad to raed wehn all the mdilde lretets of a wrod are jebumld up?

ANSWER

If you found that sentence very difficult to read, you are probably ‘over-reading’ it. If you go through slowly sounding out each word letter-by-letter, you will come up with nothing but garbage. If, on the other hand, you skim-read the sentence, just glancing briefly at each word, you will be able to read it surprisingly easily.

What’s going on here? Most people think that when we read, we do so by mentally sounding out each letter – c, a, t – and then joining these sounds together to recognise the word (cat!). While this is indeed how begnining-readers usually start out, most adults have long since largely abandoned this strategy, at least for nomral everyday reading (we keep it in reserve for reading foreign, new or very unfamiliar words). What takes its place is a process of wholeword recognition that is highly automated and extremely fast. It generally takes less than a fifth of one second to recognise a word.

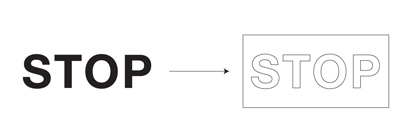

How can we recognise words so quickly? The answer seems to be that we do not, as you might imagine, read by matching the word on the page on to an exact template stored in our heads:

Printed Word / Template

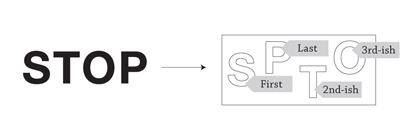

Instead, the template that is stored in our heads seems to contain just (a) the relevant letters and (b) tags indicating their approximate positions.*

Printed Word / Template

At first glance, this seems a bit odd. Wouldn’t it make more sense to store an exact template of ecah word? Well, maybe, but good luck trying. Consider a relatively long word like happiness. Even though this word isn’t that long in the grand scheme of things (it’s certainly no antidisestablishmentarianism), you have pretty mcuh no chance of storing the exact position of each letter (quick, what number position is the e in?). All you can store is some very rough positional information (‘it’s quite near the end’).

This means that when you encounter a jumbled up word such as sotp, it’s actually a pretty good match for your ‘stop’ template, and is therefore recognised relatively easily, particularly if you’re given a bit of context such as a sentence, or – say – a road sign with a distinctive shape.

To prove the point: did you notice the four words that were jumbled up in this passage?**

THE EDN

* At least, according to one recent model. If there is one thing you will never get psychologists to agree on, it is a model of visual word recognition.

** Beginning, normal, each and much.

From Psy-Q.

Ben Ambridge is Senior Lecturer in Psychology at the University of Liverpool. His article ‘Why Can’t We Talk to the Animals?’ was shortlisted for the 2012 Guardian-Wellcome Science Writing Prize. Psy-Q is published by Profile Books. Read more.

Ben Ambridge is Senior Lecturer in Psychology at the University of Liverpool. His article ‘Why Can’t We Talk to the Animals?’ was shortlisted for the 2012 Guardian-Wellcome Science Writing Prize. Psy-Q is published by Profile Books. Read more.

benambridge.wordpress.com

Follow Ben on Twitter: @benambridge