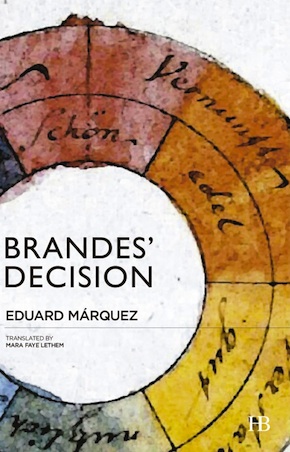

A genealogy of shadows

by Mika Provata-Carlone

“This novel resonates with detail and wonder; art, history and human experience… exciting the senses and emotions.” Irish Times

In September 1941, Walter Andreas Hofer, special art agent for Hermann Goering, was breathlessly scouring France for any and all works that might make suitable additions to his employer’s ambitious, almost gargantuan art collection. Far too often for his liking, he found himself in a mightily frustrating predicament: sequestering individual pieces or whole collections from Jews was child’s play, but what was one to do when it came to Aryans?

An ingenious, liberal process was devised for this complex quandary – after all, all Aryans may have been supremely equal, but some were certainly more equal than others. Any works, single or multiple, stored in ‘dubious circumstances’, i.e. galleries or depots under Jewish ownership or with suspected Jewish associations, were withheld pending verification, to be released after cordial negotiations and judicious persuasion as fair barter for any desirable pieces. On the 26th of that month, Hofer wrote to Goering about the particular case of Georges Braque’s Portrait of a Young Girl by Cranach the Elder. Braque had left his collection for safekeeping with his dealer Paul Rosenberg, to be kept with Rosenberg’s own pieces in the vaults of a bank in Libourne in the south of France. Rosenberg’s assets had been confiscated wholesale by the Nazis, yet the small segment belonging to Braque appeared to cause a glitch in Hofer’s process. “Braque is an Aryan who works as a painter in Paris” and there was no legal ground for sequestering his property. Yet, as Hofer writes, “I have negotiated personally with him… and indicated to him that were he prepared to sell his Cranach it would be possible to arrange a rapid release of his [remaining] collection… He has reserved the painting for us, though he had not intended to sell it, and will notify us of his decision.” Braque would be ‘selling’ his Cranach for a price that to Hofer is less than nothing: the modernist masterpieces stored alongside “are of no interest to us whatsoever,” as he makes it plain in the same report.

Márquez’ novel is a journey of memory, of recovery, of contemplation… a tactile journey through colours, textures and surfaces, their mystical meanings and stark realities.”

Hofer relished his powers of persuasion, “his was a confident voice, used to setting the terms; used to wielding fear and shattering people’s ability to choose,” as Eduard Márquez’ fictional painter Brandes recalls. To all appearances, Braque is free to make his own decision, though not his own choice, just as Brandes, in Márquez’ subtly structured novel, is ‘invited’ to do – for he too possesses a Cranach that has caught Hofer’s eye. Brandes is also an Aryan; he is moreover a German, a veteran of WWI, a painter living and working in Paris, a friend of Braque and of the Cubists. Hofer has in his hands Brandes’ entire life corpus of paintings, works that represent not only toil, but states of mind, moments of life, irretrievable traces of memory and existence. Hofer will release the confiscated collection, but he wants in return a small Cranach left to Brandes by his father.

Márquez’ novel is a journey through time, from the twilight of life back to that flaring moment of ‘decision’, as Hofer has framed it. It is a journey of memory, of recovery, of contemplation through personal experience and the voices of others, any fragments of their own experience that is available to Brandes. It is a tactile journey through colours, textures and surfaces, their mystical meanings and stark realities. Hofer’s gaze, we are told, is “Incisive. Angular as an idol sculpted by hatchet blows,” whereas Brandes’ father “could turn dry terms like lazurite, aluminium, silicate or sulphur into fascinating stories” about “the soul of colours,” art, lines, feelings, loss, life.

Brandes’ Decision is a memento mori as well as a blasting accusation – perhaps, to an extent, a self-accusation as well. “I am the last link in a genealogy of shadows. After me there will only be room for oblivion.” Brandes is dying as he is remembering, yet in this variation on the theme of the words above the gate of Hell in Dante’s Inferno, there is more than the voice of a very old man and his loneliness. The genealogy of shadows is the register of lives loved, lives lost and lives betrayed, of decisions taken, of silences kept under duress or spinelessness, or of concessions made all too unprotestingly. All his life, Brandes has oscillated between stillness and motion, passivity and action, in art as well as in life. As a painter, he has struggled with inner meaning and outer form, with movement and still lives. In his life, he has wavered between dreams and facts, the present and memory, permanence and escape. Like Braque, he has also resisted resistance – for all that he never paid allegiance to what he did not believe in. The memory of all he has or has not done, everything that he had or had not decided, now crowds even as it illuminates the end of his life.

“It would have been good to have other [teachers] to teach me how to forget, how to lose, how to resign myself… And how to die.” What makes memory inevitable and difficult is its fragility, the power of horror and shock it still and always possesses, the complexity itself of human existence. Márquez has said that “writers must be able to make the reader smell reality” and Brandes certainly succeeds in making us smell memory. Yet is memory only for those about to die? Which is the first memory, the last? How are memories determined and how do they rule over consciousness and being? Brandes feels his way back as well as forward, seeking to create, in this ledger of memory that strives for an “undistorted object of reality”, the prismatic vision of Cézanne and Braque that was so dear, so revolutionary, so unsettling and fulfilling to the Cubists, of which Brandes too was one.

In the absence of perfect memory, of proportions between its content and the clarity of its form, pain – long, unendurable, unspeakable – makes itself acutely felt. What release is there from the absence of the other? From the demise of meaning? Touchstones of memory alone make life’s journey possible against indifference and brutality, yet there is always the moment of reckoning: what is true resistance to death? To historical evil or personal tragedy? One of Brandes’ central anxieties is how not to be overtaken by time, or a more metaphysically understood death, in one’s effort not to be destroyed – in the effort to survive. That, of course, requires a close scrutiny of the role of the individual, especially of the intellectual and the artist, in a time of historic crisis. Braque, Cézanne, Le Corbusier, innumerable others, sat out the time of the Occupation (some even lent their offices to the Occupier by joining on an artistic tour of Germany), and Brandes struggles to come to terms, under Hofer’s pressure, with his own instinctual, centripetal movement, if not inertia.

This is a fine, complex, truly multifaceted book, where many wavelengths of conscience and strands of vision tangle and fuse without ever getting blurred or tainted.”

Jed Perl has written that “Picasso celebrates animation, while Braque celebrates contemplation” and this was true not only in terms of their aesthetic temperaments and stylistic choices. Brandes is on the fence between such animation and contemplation, between action and non-action, surrender and resistance. The ‘active passivity’ of Braque, celebrated and memorable in his vanitas series of black fish evoking Emile Gallé’s reaction to the Dreyfus affair Les Hommes noirs, the skulls that begin to appear in Braque’s paintings in 1937 and disappear after the war, is critically vital but not sufficient for Brandes, whose own decision seems as Ibsenian as the resonances in his name. His journey of memory is in its essence the desperate quest for the redeeming moment of action – the single act that proves he did not abandon humanity, even at the heart of the inferno. It is also a personal duel with Hofer – who survived the war mainly unscathed and resumed his life in Munich as a reputable art dealer. Perhaps it is also an inquiry into Goering’s fascination with Cranach, so incongruent, if one looks at it closely, from its own historical context. Cranach, the friend of Luther, the duke’s painter, was as ‘degenerate’ and subversive in his choice of subject matter as Otto Dix, Marc Chagall, Braque – or Brandes himself – in his sensuously indulgent depictions of nudes from mythology and religion.

We do not know Braque’s final response to Hofer – he seems, the historians have concluded, to have procrastinated tenaciously. His Cranach was not found among the artworks Hofer plundered for himself, and according to Braque’s biographer Alex Danchev, the famous Collection Goering: Inventaire des peintures, the painstaking and exhaustive handwritten list kept on Goering’s desk for quick reference, does not mention Portrait of a Girl. Brandes will not procrastinate beyond the pages of Márquez’ original, deftly crafted novel, and his own decision is a masterly literary conceit, as well as a gesture of triumph and lively dignity. This is a fine, complex, truly multifaceted book, in an elegant, flowing translation by Mara Faye Lethem, where many wavelengths of conscience and strands of vision tangle and fuse without ever getting blurred or tainted. It is a lucid chronicle of history and historical perspective, of lives lived and their stories, a delicate tribute to the art of painting and reflection, to the true art that, according to Braque, is life.

Eduard Márquez published two books of poetry in Spanish before writing the story collection Zugzwang, his first work in Catalan. He has continued writing in Catalan, publishing another collection of short fiction, fifteen children’s books, and four novels. Brandes’ Decision, translated by Mara Faye Lethem, is published by Hispabooks.

Eduard Márquez published two books of poetry in Spanish before writing the story collection Zugzwang, his first work in Catalan. He has continued writing in Catalan, publishing another collection of short fiction, fifteen children’s books, and four novels. Brandes’ Decision, translated by Mara Faye Lethem, is published by Hispabooks.

Read more.

@Hispabooks

Author portrait © Toni Coll Tort

Mara Faye Lethem is a Brooklyn-born, Barcelona-based writer and literary translator. Her translations include novels by Jaume Cabré, David Trueba, Albert Sánchez Piñol, Javier Calvo, Patricio Pron, Marc Pastor, Toni Sala and Sara Moliner.

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.