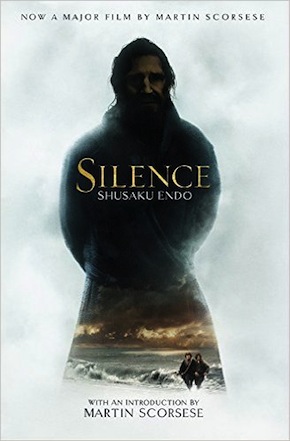

On Silence

by Martin Scorsese

“One of the finest novels of our time.’” Graham Greene

How do you tell the story of Christian faith? The difficulty, the crisis, of believing? How do you describe the struggle? There have been many great twentieth-century novelists drawn to the subject – Graham Greene, of course, and François Mauriac, Georges Bernanos and, from his own very particular perspective, Shusaku Endo.

When I use the word ‘particular’, I am not referring to the fact that Endo was Japanese. In fact, it seems to me that Silence, his greatest novel and one that has become increasingly precious to me as the years have gone by, is precisely about the particular and the general. And it is finally about the first overwhelming the second.

Endo himself had great difficulty reconciling his Catholic faith with Japanese culture. So it was not historical research but his own experience that drew him to the stories of the Portuguese missionaries of the seventeenth century who were forced to apostasise. He understood the conflict of faith, the necessity of belief fighting the voice of experience. The voice that always urges the faithful – the questioning faithful – to adapt their beliefs to the world they inhabit, their culture. Christianity is based on faith, but if you study its history you see that it’s had to adapt itself over and over again, always with great difficulty, in order that faith might flourish. That’s a paradox, and it can be an extremely painful one: on the face of it, believing and questioning are antithetical. Yet I believe that they go hand in hand. One nourishes the other. Questioning may lead to great loneliness, but if it co-exists with faith – true faith, abiding faith – it can end in the most joyful sense of communion. It’s this painful, paradoxical passage – from certainty to doubt to loneliness to communion – that Endo understands so well and renders so clearly, carefully and beautifully in Silence.

Endo understood that, in order for Christianity to live, to adapt itself to other cultures and historical moments, it needs not just the figure of Christ but the figure of Judas as well.”

Sebastian Rodrigues represents what you might call the ‘best and the brightest’ of the Catholic faith. “There were once ‘Men of the Church’,” the old Priest of Torcy tells the young, sickly Priest of Ambricourt in Bernanos’ Diary of a Country Priest, and Rodrigues would most certainly have been one of those men, stalwart, unbending in his will and his resolve, unshakeable in his faith – if he had stayed in Portugal, that is. Instead, he is tested in a very special and especially painful way. He is placed in the middle of another, hostile culture, during a late stage in a protracted effort to rid itself of Christianity. Rodrigues believes, with all his heart, that he will be the hero of a Western story that we all know very well: the Christian allegory. He will be the Christ figure, with his own Gethsemane – a patch of woods – and his own Judas, a miserable wretch named Kichijiro. In fact, this is the fate that befalls his fellow missionary, Father Garrpe.

And then, slowly, masterfully, Endo reverses the tide. Why am I being kept alive? Rodrigues wonders. Where is my martyrdom? My glorious martyrdom? His Japanese captors have a keener understanding of Christianity than he realises, and he is given a different role altogether, although no less meaningful.

Silence is the story of a man who learns – so painfully – that God’s love is more mysterious than he knows, that He leaves much more to the ways of men than we realise, and that He is always present… even in His silence. For me, it is the story of one who begins on the path of Christ and who ends replaying the role of Christianity’s greatest villain, Judas. He almost literally follows in his footsteps. In so doing, he comes to understand the role of Judas. This is one of the most painful dilemmas in all of Christianity. What was Judas’ role? What was expected of him by Christ? What is expected of him by us today? With the discovery of the Gospel of Judas these questions have become even more pressing. Endo looks at the problem of Judas more directly than any other artist I know. He understood that, in order for Christianity to live, to adapt itself to other cultures and historical moments, it needs not just the figure of Christ but the figure of Judas as well.

I picked up this novel for the first time twenty years ago. I’ve reread it countless times since. It has given me a kind of sustenance that I have found in only a very few works of art.

This introduction to Shusaku Endo’s Silence is reproduced by permission of Peter Owen

Martin Scorsese is the multiple award-winning director of landmark films including Mean Streets, Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, The Last Temptation of Christ, Goodfellas, Gangs of New York, The Aviator and The Wolves of Wall Street. His adaptation of Shusako Endo’s Silence starring Liam Neeson, Adam Driver and Andrew Garfield, is released on 23 December in the US and 1 January in the UK.

Shusaku Endo is widely regarded as one of the greatest Japanese authors of the late twentieth century. Born in 1923, he won many major literary awards and was nominated for the Nobel Prize several times. His novels, which have been translated into twenty-eight languages, include The Sea and Poison, Wonderful Fool, Deep River, Silence and The Samurai. He died in 1996. Tie-in editions of Silence are published by Peter Owen in hardback and Picador in paperback, translated by William Johnston. Peter Owen also publish Endo’s extensive backlist. Read more.