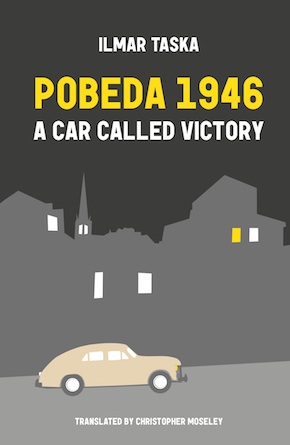

A splendid shiny car

by Ilmar Taska

“An elegant novel about the reality of an occupied country.” Sofi Oksanen

The boy had to be silent again. Daddy said, with a frown as always: “Don’t talk so loudly.”

“He can talk,” interjected his mother, “but you have to be quiet and don’t boom in your deep bass.”

But what’s the use of talking alone, thought the boy, if Daddy isn’t allowed to answer and Mummy doesn’t want to?

The room was dark and gloomy. The boy climbed onto the windowsill and looked out between the curtains. The street was getting dim and damp as well. Yet muted lights shone from the windows of the house next door and the boy saw shadows moving. They were running, playing, maybe even laughing there.

His mother said in a quiet, scolding tone: “Close the curtains.”

The boy was sad that his father was sullen, while his mother was always angry about something. Mummy was always busy, making meals, washing dishes, ironing clothes, mopping the floors, darning socks. Always in silence. She didn’t like the boy laughing, shouting, or asking her anything. She liked it even less when Daddy did it. He wasn’t allowed to talk at all. Not to go to the door or the window. He always had to hide from everyone, but he never wanted to play hide-and-seek with the boy. He sat or lay in the back room, reading old, bad-smelling books. Once the boy had found an old photograph album with pictures of Mummy and Daddy in which they were laughing and beautiful.

“Now you look quite different. Horrible,” the boy had said, at which his mother took the album from his hands and put it on a high shelf, so that the boy could no longer get at it.

“I’m bored,” he told his father. Daddy was smoking, and didn’t raise his eyes from some old magazine with yellowed pages.

“You want to look at pictures of tanks and armoured cars?” asked his father. Those pictures the boy had seen countless times, however, and knew the make of every armoured car by heart.

“May I go outside and play?”

“Off you go,” said Daddy, without looking up.

“But not far from the house,” warned his mother, nervously brandishing the iron.

The boy climbed down from the woodpile and stepped closer to the Pobeda, curiously, his heart pounding. He had seen beautiful cars before, but none so brilliant and new.”

The boy was already grabbing his cap and sprinting out into the brisk air. He climbed onto a woodpile on the other side of the street and sat down on a thick log that extended from the stack, as it rocked under his weight. Finally he was back in the driver’s seat. He switched on the engine, put it into gear and felt the bus starting to move under him. He rocked himself on the wooden seat as he drove along the potholed road, and the noise of his bus got louder when he changed gear. As he drove and battled with the bumps in the road, he noticed two lights approaching from the end of the street. A splendid shiny car was slowly approaching. It was brand new, and beige in colour.

“Psssh” – the boy was pressing the button to open the bus doors. “Last stop! All passengers please get off.”

The approaching Pobeda had stopped on the other side of the road. The boy climbed down from the woodpile and stepped closer to the Pobeda, curiously, his heart pounding. He had seen beautiful cars before, but none so brilliant and new. Sitting in it was a tallish man in a grey coat, who had noticed the boy and was looking at him, smiling broadly. He didn’t get out of the car or turn off the engine. The boy approached the car with a self-conscious gaze. He made a circuit around the car, bent down behind it and sniffed the exhaust-pipe gases. Even that smelled wonderful. The man wound down the car window and leaned his head out toward the boy: “Do you want to be a car mechanic?”

“No, a bus driver,” replied the boy.

“So cars don’t interest you much?”

The boy moved alongside the car closer to the man, rose on tiptoe and looked in the window. Coloured lights shone on the dashboard and the seats were covered in leather.

“Do you want to get in?” the man asked the boy with a friendly glance. The boy knew that he mustn’t talk to strangers, but sitting in a car like this was worth breaking the rules for. He could simply sit in it quietly. The man opened the door, stretched out his warm hand and pulled the boy up onto the seat. He looked slyly at the boy and flashed the dashboard lights to please him. The man laughed. His hair was nicely styled and he was clean-shaven, not like Daddy. It was hard to sit silently when such an amusing man was wanting to chat. And they did chat for a bit, about cars.

Then the man inquired: “What’s your name? Where do you live?” The boy didn’t answer those questions. Mummy had forbidden him to answer such questions. He didn’t understand why, but Mummy and Daddy didn’t let him talk to strangers. He stretched out his arms and tried the steering wheel. It was cold, smooth and curved. How nice it would be to hold onto, not like the stick with which he drove his bus. The man seemed to read his thoughts, shifted aside and said: “Come, sit closer and hold onto the wheel like proper bus drivers do.” The boy placed both hands on the wheel and looked straight ahead through the windscreen. The man pressed some button and the wipers suddenly sprang into action. The boy squealed in surprise and they both laughed. The man took the boy’s hand, pressed the button again and the wipers stopped.

“Now you try. Does your father have a car too, or does he go by bus?” asked the man.

“My Daddy doesn’t go out at all,” the boy blurted out. He looked at the man, startled. But the man only smiled. He stared deep into the boy’s eyes and replied, almost consolingly, “Not all guys are car enthusiasts like we are.” This man can be trusted, the boy thought.

“My Daddy is only interested in tanks and armoured cars.” But now his mother’s perpetual warning rang in his ears again: “Never talk about Daddy to anyone.”

From Pobeda 1946: A Car Called Victory (Norvik Press, paperback, £11.95)

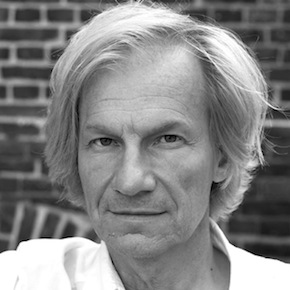

Ilmar Taska was born in Kirov, Russia, where his family had been sent from Estonia under Stalin’s repressions. He grew up in Estonia and studied at the Moscow Film Institute. As a director and producer his films include Set Point and Thy Kingdom Come (a.k.a. Wings of Fear. His debut novel Pobeda 1946: A Car Called Victory is based on an award-winning short story from 2014 and is translated by Christopher Moseley.

Ilmar Taska was born in Kirov, Russia, where his family had been sent from Estonia under Stalin’s repressions. He grew up in Estonia and studied at the Moscow Film Institute. As a director and producer his films include Set Point and Thy Kingdom Come (a.k.a. Wings of Fear. His debut novel Pobeda 1946: A Car Called Victory is based on an award-winning short story from 2014 and is translated by Christopher Moseley.

Read more

Christopher Moseley is a freelance translator into English from Estonian, Finnish, Latvian, and the Scandinavian languages. His previous translations include Andrus Kivirahk’s The Man Who Spoke Snakish (Grove Press, 2017). He teaches English and Latvian at the School of Slavonic and East European Studies, University College London.