It started with a chair

by Charlotte Leonard

“Heartbreaking, emotional and truly uplifting” Read more

I’d been swimming in the Ladies’ Pond on Hampstead Heath and was walking home along the lane, stomping colour back into my toes, when I bumped into a lifeguard friend who I hadn’t seen for a few weeks. When she isn’t at the pond, she’s usually making giant sculptures, weaving willow into stunning shapes. But not this time. She said that she’d been busy, using her allotted leave to make a chair. I imagined her at home in London with a screwdriver, an Allen key, a box of flat-pack furniture and some illustrated instructions from Ikea.

‘No,’ she said, ‘I made a chair. An actual chair!’

It transpired that she’d been staying in a forest in the West Country on a residential course where participants each select a tree and chop it down. They then use the tree to make a chair with tools held in their hands. Apparently, the making of a chair requires all of you – your time, imagination, concentration, and full strength. She explained she’d always known she had a chair in her and that she’d felt the desperate need to ‘get it out.’ This statement made me think. I knew instinctively that I didn’t have a chair in me. Not even a three-legged stool. At a push, perhaps a simple spoon or a very basic spatula. But I did have books. As opposed to wooden shapes and contours and practical possibilities I was filled with words, stories, and characters. If only I could ‘get them out.’

Following in my friends’ footsteps I decided that a course would be the best way to begin to carve and shape a book. I wanted the community, the structure that a course provides and the opportunity to be immersed inside the woods of novel writing. Searching the internet, I settled on Faber’s online ‘First 15,000 words’. The application for the course required a plot synopsis for the book I planned to write. Panic ensued. I didn’t have a book planned out. I didn’t even have a plot. What topic should I focus on?

At the time the subject of male suicide was being frequently discussed inside our home. Two years before I applied to start the course, we had taken our young sons to watch Linkin Park perform at the O2. Just weeks later Chester Bennington had hung himself. Our sons were all deeply distressed, not only by the singer’s death, but by the fact he’d left behind six children and a wife. I suddenly found myself having conversations for which I wasn’t in the slightest bit prepared.

Mental health is being talked about more openly and frequently, yet suicide is often shrouded in thick silence. There is a stigma still.”

Over the next few years people carried on dying at an alarming rate. Mike Thalassitis from Love Island hung himself in a park close to our London home. And it wasn’t just celebrities. An extended family member died. Friends were losing friends and siblings, parents, partners and children. Almost everyone I knew had been impacted by a suicide, something which is sadly unsurprising given the statistics. Suicide is the biggest killer of people under the age of 35, more deadly than both cancer and car crashes, and it’s mostly men who die. In 2021 three quarters of all suicide victims were male.

As a woman, wife, and mother of three sons the risks surrounding suicide feel both personal and frightening. I felt compelled to write about those left behind and so I began researching. A few things quickly became clear. Mental health is being talked about more openly and frequently, yet suicide is often shrouded in thick silence. There is a stigma still. Additionally, the grief experienced by those bereaved is particularly complex. It is a complicated loss, with suicides often raising questions that have no clear or obvious answers. And finally, it is possible to survive the trauma of such a heartbreaking and tragic loss. With the support of other people there is always, always hope.

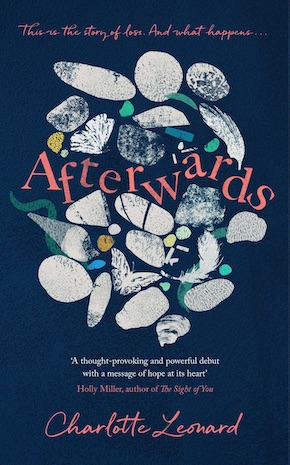

So I focused on what happens afterwards, to the loved ones who are grieving. My novel tells the story of Emma, happily married to a man she thinks she knows, who finds her whole world shattered when her husband commits suicide. Jay, a commercial photographer, leaves no letter to explain. Emma is left with only Jay’s camera containing five photographs and a house that no longer feels like home. Struggling to cope, she focuses on the images, which lead her on a journey in which old relationships are rewritten and new ones are formed. As the visual mystery of each photograph unfolds, Emma begins unravelling too. She finds salvation in the sea, a small community of swimmers and the promise of a future that she hadn’t planned.

The book is ultimately hopeful.

It focuses on family and community, on cold-water swimming and the sea.

It is intended as a love letter to life.

After the course finished, I set myself a weekly goal of words to write. I wrote page counts on bright Post-it notes in black biro and stuck them to the outside of the cupboards in the kitchen. Every time I reached the requisite number of words, I threw a note into the bin. For someone who is often in the kitchen and likes everything to be tidy, this was hugely motivating. Some days the words came easily, and other days writing felt like trying to extract blood from granite stone or chiselling a chair from a felled tree.

I finished an initial draft the day before the first lockdown. A few weeks later I submitted the rough manuscript to the Bath Novel Awards, under the name ‘The Afterdrop,’ where it was longlisted, then shortlisted. An amazing agent took me on, and just before Christmas that year I signed a publishing contract with Simon & Schuster. More time was spent carving out the characters, shaping sentences and polishing the plot until the words became a finished book. A book you can read sitting in a chair. A chair that wasn’t carved by me.

Charlotte Leonard lives with her husband and three sons in London. Afterwards, her first novel, is published by Simon & Schuster in hardback, eBook and audio download.

Charlotte Leonard lives with her husband and three sons in London. Afterwards, her first novel, is published by Simon & Schuster in hardback, eBook and audio download.

Read more

@Ms_C_Leonard

@simonschusterUK

Author portrait © Rankin