Stitching up our mouths

by Miranda DoyleThe first copies of the paperback edition of The Book of Untruths have arrived and again I am awake for hours in the night. This has happened before. A sleeplessness which is kicked off by the unintended consequences of writing a life. Needing soothed I message the poet Joanne Limburg, who has given much thought to the ethics of memoir.

Joanne is the author of Small Pieces and we meet in a cafe, our table surrounded by students on laptops with stopped ears. I wonder if they’re listening to music or just shutting out our noise; our talk; us.

Stopped ears is at the heart of a decision to write testimonial life narratives, from Primo Levi’s If This is a Man to Rose McGowan’s Brave. There is a need to articulate what is unspeakable. Small Pieces is a memoir with Judaism at its core, which tells the aftermath of a brother’s suicide. Writing in The Guardian the journalist Christina Patterson tells us that after reading she was in pieces, a howling wreck.

Suicide is a word that tends to cause others to lower their voice. When I ask Joanne if Small Pieces comes from a desire to kick shame into the long grass, she says that “a blow to silence” is a huge motivator in her writing: “injustice and oppression flourish in the dark.” What she means is not a respectful silence, but the ‘we don’t talk about it’ silence, or ‘nobody wants to hear you’ silence. “All those things that stitch your mouth up.”

She is right, silence is corrosive. To me it is synonymous with deceit. Many of the untruths that map my life were not about telling a lie, but a relentless omission of the truth. My grandfather for instance, although dead to Dad, knocked around an insane asylum without visitors for twenty-four years. Crazy and alive. What fascinates is the irony that the ethical arguments around this genre are one way of muffling those who try to speak.

Privacy does not protect the dead. But what of the living, especially the young?”

When I ask why her PhD focused, in part, on the ethics of life writing, Joanne tells me that to write about her brother was “uncomfortable”. Although there was a strong sense of compulsion, there was a strong sense of prohibition too. It was only after her mother’s passing that she felt released. Death was a contributory factor in my own writing too. After my parents were gone they were no longer able to hold their fiction together. It became a story to steal.

Privacy does not protect the dead. But what of the living, especially the young? The publication of James Rhodes’ Instrumental was delayed due to an injunction brought by his ex-wife in order to protect their son from reading about his father’s abuse. Kathryn Harrison’s The Kiss was roundly criticised for the effect it might have on her daughters. I ask Joanne whether a desire to protect children had an impact on her.

“It was absolutely vital that I protect them, because having already published a memoir I had already been treated like a character, and knew what the consequences of that can be. Children are vulnerable subjects. There’s a structural inequality of power between a parent and a child, and we owe it to them to exercise that power responsibly. However, apart from withholding names, I left nothing out in order to protect my niece, or my son. They have always known the truth.”

“It was absolutely vital that I protect them, because having already published a memoir I had already been treated like a character, and knew what the consequences of that can be. Children are vulnerable subjects. There’s a structural inequality of power between a parent and a child, and we owe it to them to exercise that power responsibly. However, apart from withholding names, I left nothing out in order to protect my niece, or my son. They have always known the truth.”

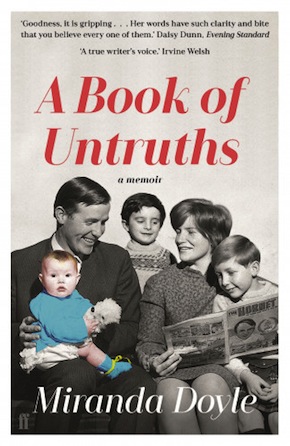

Truth-telling is an ethical requirement, but also an imperative for autobiography. Without truth this genre falls into fiction, and privacy and freedom of expression hold no ground. Chronically lied to and disbelieved truth has never been something I can be confident about. It became the reason why my memoir has the title A Book of Untruths. The only way to draw a line on deceit was to put my back to it. The Irish Times says these stories are “ablaze with veracity” and that kind of telling, to those closest to us, can be painful. One aunt drove an hour to a book event in Edinburgh to heckle from the back.

For those of us who write memoir it’s not the extremes of privacy and expression that are most uncomfortable, it’s the deep respect we feel for those we have loved.”

We feel, each one of us, that at the very least we own our own story. Brandeis and Warren, writing in the late nineteenth century, argued that every individual has the right to his or her own “inviolate personality”. Their essay was the first to advocate a ‘right to privacy’, a right which, at the cost of freedom of expression, was hard fought during the Leveson Inquiry. The author D.J. Taylor, told by his solicitor to immediately get all his property into his wife’s name, feels that the law is stacked against the writer.

However, for those of us who write memoir it’s not the extremes of privacy and expression that are most uncomfortable, it’s the deep respect we feel for those we have loved. What keeps us awake at night is how to be honest about them and how to be fair. We agree with Jeffrey Rosen, when he writes in The Unwanted Gaze, that there can be “few acts more aggressive than describing someone else.”

I have appropriated the lives of my siblings, turning them into characters that they don’t recognise, and purely for my own gain nailed them to the page. Joanne calls this “creative capital”. For the surviving sibling following a suicide, she says: “you can feel accused by it. To write felt like proof that I was selfish, and that I was bad. That I took and didn’t give.”

The self cannot be separated from the selves around it. The lines between you and me fudge, a boundary which with my brothers is holed and broke. The bigger the story a family tells, the more complicit its children become in that tale. Our privacies are shared, relational. The suicide of a sibling is one of the most indissoluble events in a person’s life, the fact of it stitched in.

“There’s an obligation to be careful when we write,” Joanne says, “but there’s also an ethical obligation to speak.” The #MeToo movement, she points out, is speaking ethically. “Without bearing witness we allow things to be erased.” So as readers it can be ethical for us to reach out, ethical to unstop our ears, to read, to listen and to hear.

Miranda Doyle’s family come from the tiny island of Coney in Sligo Bay. She grew up in Edinburgh. With an MA from Goldsmiths in Creative and Life Writing she has lectured on Autobiography for the Philosophy and European Literature degree at Anglia Ruskin University and continues to teach creative writing. A Book of Untruths, her debut book written with the support of an award from Arts Council England, is out now in paperback from Faber & Faber.

Miranda Doyle’s family come from the tiny island of Coney in Sligo Bay. She grew up in Edinburgh. With an MA from Goldsmiths in Creative and Life Writing she has lectured on Autobiography for the Philosophy and European Literature degree at Anglia Ruskin University and continues to teach creative writing. A Book of Untruths, her debut book written with the support of an award from Arts Council England, is out now in paperback from Faber & Faber.

Read more

bookofuntruths.com

@Miranda_J_Doyle

Author portrait © Mark Turner

Joanne Limburg’s memoirs Small Pieces and The Woman Who Thought Too Much, and her novel A Want of Kindness are published by Atlantic Books.

Read more

joannelimburg.net

@JoanneLimburg