Suzie baby

by Mahesh Rao

“One of the finest books to come out of India this year.” Mirza Waheed

Murders: forty-seven. Kidnappings: fourteen. Attempted rapes: five. Car chases: fourteen. Hijacks: two. Helicopter jumps: one. Smuggling expeditions: countless.

It’s not exactly Sir Laurence Olivier. But in summing up my film career, mendacity will serve no one. I have acted in eleven films, three of which were shelved: two for financial reasons, the third as a result of the producer’s conviction in a racketeering case. Of the eight releases, two were declared super hits, two did average business and the rest were wholly rejected by the masses.

These days I have opted for a simple life, free from the trilling of the film world. But I continue to be connected to my métier through my acting academy, where I give classes four days a week. The location, one of the studios of an unkempt gym in Jogeshwari, is not ideal. It is, however, quite close to my home, the rent is reasonable, and I am able to occupy the room at non-peak hours when the din of the aerobics classes is only an unpleasant memory.

Abhay has been training at my academy for just under a year. He is twenty-six and pleasant. He has a hard, athletic body over which he lavishes much care and a singularly naïve face. The overall impression he gives is that of a calf in a tight T-shirt. Over the last few weeks he has desecrated numerous iconic monologues, misunderstood almost every aspect of improvisation and, with the assistance of four fellow students, enacted a ghastly comedy routine. He also sings, although thankfully, not at me.

Abhay tells me that he has reached a crucial point in his journey. A few weeks ago his regular attendance outside the office of a prominent producer finally yielded a result. He was allowed into the sanctum sanctorum to meet the great man. His photographs were accepted and I have no doubt that his journey was discussed. A week or so later, quite surprisingly, he was summoned to the producer’s offices again, where he met a few more notable personalities, I forget whom. The following day he was asked to do a screen test. There may have been other readings and run-throughs. With all this background activity, he stopped attending classes. I said nothing of it. It is not my concern whether they show up or not. Drag a horse to water and so forth.

I told him I had always believed that his capability and dedication would bring him the success he deserved. He had tears in his eyes. Maybe he really does have some acting talent.”

Yesterday Abhay turned up just as my class was ending. He wanted to have a private word. He told me that discussions with the film producer had reached an advanced stage. It was ninety-five per cent guaranteed that he had secured the role of the second lead in a big banner film. The producer’s assistant had informed Abhay that a decision was imminent and that he would be telephoned around four the next afternoon.

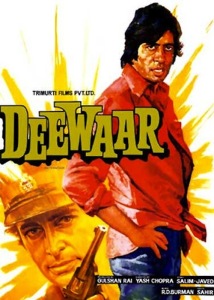

Deewaar (The Wall, 1975), directed by Yash Chopra, was the film that established Amitabh Bachchan as the angry young man of Bollywood. Wikimedia Commons” width=”210″ height=”294″>I congratulated Abhay. I told him that I had always believed that his capability and dedication would bring him the success he deserved. He had tears in his eyes. It could have been the emotions of the past few days or maybe he really does have some acting talent.

Deewaar (The Wall, 1975), directed by Yash Chopra, was the film that established Amitabh Bachchan as the angry young man of Bollywood. Wikimedia Commons” width=”210″ height=”294″>I congratulated Abhay. I told him that I had always believed that his capability and dedication would bring him the success he deserved. He had tears in his eyes. It could have been the emotions of the past few days or maybe he really does have some acting talent.

As I was preparing to leave the room, he fell to the ground and tried to touch my feet. Naturally I recoiled. He had one more thing to ask me, he said. Would I please wait with him the following afternoon when the call from the producer’s office was due? I was, he said, like a father to him and he believed I would bring him good luck. I may have ordered an elderly invalid to be torn apart by wild dogs in one of my films but I am not a monster. I could hardly refuse with the boy trembling at my feet like a TB patient. Just this once I decided to indulge poor, witless Abhay.

And so I find myself sitting here with him in a cheap restaurant, a place that he assured me would be empty at this time. Naturally it is not, and from time to time all we can hear is the sound of waiters bellowing their orders to the kitchen.

And in any case, there will be no call. There will be no second-lead role. There will be no big banner film; at least, not for Abhay. I am not sure if Bombay film producers are congenitally sadistic or whether boredom drives them to these acts. What I do know is that there have been innumerable instances of firm promises, accompanied by a ceremony of meritocratic selection, none of which has resulted in so much as a walk-on part in a horror film. I have seen it happen time and time again. I suppose I should feel sorry for Abhay, but if he still has not learnt these basic facts, he probably deserves the thrashing he is due to get.

He seems oblivious to the fact that we are only a couple of feet away from the bedlam of the Jogeshwari–Vikhroli Link Road. Bombay has changed immeasurably. For one thing, we are encouraged to call it Mumbai. The JVLR is now a multilane colossus that apparently makes life much easier for commuters. That is for others to comment on since I no longer drive and my life takes me no further from Andheri than Jogeshwari. The property prices, the pollution, the policing: all changes very dear to the hearts of the bourgeois occupants of my building but of little interest to me.

I was lucky. Unlike most actors, I had both ambition and insight. In time I came to see that my imposing stature and patrician mien could be assets in the field of cinematic depravity.”

There is a certain pleasure in teaching these youngsters, regardless of the fact that most are no better than chimps swinging in a zoo. I coach acting as science: psychology, physics and anatomy. I provide sessions in body language, expressions, voice modulation and character deconstruction. There are practical aspects too, such as camera angles and the pitfalls of auditions. I do not teach fighting or dancing. They can easily learn that elsewhere. Some of them are disappointed when they discover that action sequences will not be on the curriculum. Given my past, they probably arrived here thinking it would be the most prominent area of instruction.

* * *

I did not set out to hold sway as one of Hindi cinema’s most barbarous villains. Like many of my colleagues who found themselves looting temples and silencing informants, I ventured into the film industry hoping to be cast in romantic lead roles. It is true that someone of my elite drama school training would have been expected to have a natural inclination for the stage. But I was convinced that I could add a dash of refinement to the mainstream medium, expunging its gaudiest strokes. I spent years supplicating and genuflecting, trying to melt hearts and set fire to loins. It was not to be. I was routinely ignored, insulted or dismissed. Nevertheless, I was lucky. Unlike most actors, I had both ambition and insight. In time I came to see that my imposing stature and patrician mien could be assets in the field of cinematic depravity.

Himalaya Ki God Mein (In the Lap of the Himalayas, 1965), directed by Vijay Bhatt. Wikimedia Commons” width=”200″ height=”289″>It seems strange to recall those times in this restaurant, surrounded by various employees of a nearby hospital, identifiable by the grubby passes they are still sporting around their necks. There are so many streaks and scratches on the laminated surface of the menu that it looks like a piece of frosted glass. Abhay could at least have picked a place with air conditioning. It is October, Bombay’s second summer, and my shirt is beginning to stick to my back even though I am not normally given to extravagant perspiration. This was always an advantage when I used to film. Shooting under studio lights, or on a scorching airfield runway, or sometimes in the humidity of Madh Island, I was able to perform take after take with little or no retouching by the make-up assistant. No mean feat when one considers that I would probably have been in a wide-lapelled cream sports jacket or a three-piece suit.

Himalaya Ki God Mein (In the Lap of the Himalayas, 1965), directed by Vijay Bhatt. Wikimedia Commons” width=”200″ height=”289″>It seems strange to recall those times in this restaurant, surrounded by various employees of a nearby hospital, identifiable by the grubby passes they are still sporting around their necks. There are so many streaks and scratches on the laminated surface of the menu that it looks like a piece of frosted glass. Abhay could at least have picked a place with air conditioning. It is October, Bombay’s second summer, and my shirt is beginning to stick to my back even though I am not normally given to extravagant perspiration. This was always an advantage when I used to film. Shooting under studio lights, or on a scorching airfield runway, or sometimes in the humidity of Madh Island, I was able to perform take after take with little or no retouching by the make-up assistant. No mean feat when one considers that I would probably have been in a wide-lapelled cream sports jacket or a three-piece suit.

My first and biggest success was Dushman ka Khoon (1976). I spotted recently on several websites that the title has been translated into English as The Enemy’s Blood; I think Enemy Blood, eschewing the definitive article and the possessive form, would have been more elegant. I understand also that a DVD version of the film is circulating in Southall and other ethnic localities of British cities with the subtitle Sinister Revenge. No doubt those in charge know what they are doing.

Details of the denouement are unnecessary: suffice it to say that I was endowed in this film with a glass eye, an underwater hideout and a leopard on a leash. The vamp assigned to me was initially called Maria. But in the course of filming, the character’s name was changed to Suzie, with its frisson of promiscuity.

And that brings me to what has perhaps become my most important legacy in Indian popular culture: the phrase that is still occasionally shouted at me from taxis and construction sites.

“Suzie baby, why don’t you come a little closer?”

The line had initially been conceptualised in Hindi, “Suzie baby, zara paas aake baitho na,” but it was felt that my delivery of the words in English achieved a more precise lewdness. I remember clearly the day that we filmed the scene. I had rehearsed the line in Hindi a couple of times and the director, Murad Khan, remained unconvinced. There was something about the purity of my intonation that did not accord with the revolving bed on which I sat. It occurred to me that a simple switch to English might solve the problem. So not only did I deliver the line, in a small way I was also responsible for its creation.

Sulochana had a strange, disorderly beauty on screen. I suppose that these days she would be considered somewhat full-figured. Then she was thought to have a very covetable shape, all snap and sway.”

There are those who continue to carp that we simply copied the other popular catchphrase of the era: “Mona darling”. I concede that there is a degree of semblance. This line too was uttered in a number of films by a celebrated villain of the seventies, Ajit, to his scantily clad female sidekick. Like me, Ajit represented the more polished criminal, a blackguard with class. But any similarities must end there. For one thing, he was a good many years older than me. He also possessed an acting style that was antithetic to mine, favouring a rather broad and conspicuous projection.

In terms of the line itself, taken in context, there is a world of difference between “Suzie baby” and “Mona darling”. A proper elucidation would require a forensic enquiry into the plots of our various films so I will only repeat what was once said by Jean-Luc Godard: “Cinema is not an art that films life; it is something between art and life.”

* * *

Suzie was played by a young actress called Sulochana Ganapathy. Her family was originally from Hassan in Karnataka, but having grown up in Lucknow, she spoke the most elegant Hindi. It was unfortunate that most of her negligible lines were in English. Her name was considered inappropriate for a siren so she was given the screen name Roshni Rani. I doubt whether she had any say in the matter.

Sulochana had a strange, disorderly beauty on screen. Her face was a little elongated, her eyes tended to look surprised and she could bring a nuanced tremble to her bottom lip, barely perceptible to the naked eye. I suppose that these days she would be considered somewhat full-figured. Then she was thought to have a very covetable shape, all snap and sway. She was a classically trained dancer, Bharatanatyam, I believe. In Dushman ka Khoon she made her entrance sliding down a chute into a tub of foam.

I met Sulochana on the first day of filming. She had been living some sort of hand-to-mouth existence as a junior artist, her unfortunate tale no different from all those other thousands. Her experiences had already given her face the expression much seen in the Bombay film world, part earnest, part craven. That film was her break, as it was mine. Although to witness our brief conversations in between shots, anyone would have thought that I was already a huge star. She deferred to everything I said, no matter how desultory. She asked me endless questions about her expressions, her poise and her accent. I was probably quite dismissive. She irritated me. What had poise got to do with sprawling half-naked on a mound of fake bank notes?

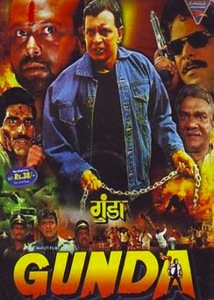

Gunda (Kanti Shah, 1998). Wikimedia Commons” width=”200″ height=”280″>Sulochana was cast as my chief moll in two further films. Producers must have appreciated a certain celluloid chemistry between us. Either as some form of branding or out of creative sloth, her character’s name remained Suzie in both films. It seemed inevitable then that my much-appreciated line from Dushman ka Khoon would be repeated a number of times whenever we shared the screen. I think I spent a good part of the late seventies encouraging Sulochana to come a little closer.

Gunda (Kanti Shah, 1998). Wikimedia Commons” width=”200″ height=”280″>Sulochana was cast as my chief moll in two further films. Producers must have appreciated a certain celluloid chemistry between us. Either as some form of branding or out of creative sloth, her character’s name remained Suzie in both films. It seemed inevitable then that my much-appreciated line from Dushman ka Khoon would be repeated a number of times whenever we shared the screen. I think I spent a good part of the late seventies encouraging Sulochana to come a little closer.

By chance, I saw Sulochana about ten years ago. She must have been in her early fifties then. It was the first time that we had seen each other since dubbing for the last film we did together in 1979. The occasion was not a happy one. It was the fourteenth day ceremony of Vishal Patil, a character actor who had shown me a number of kindnesses in my days as a novice. He had succumbed to a heart attack and, being well liked in the industry, had attracted a large gathering of mourners.

I was taken aback to see Sulochana there. I had heard that she had married and left Bombay. She seemed genuinely pleased to see me. I am not sure why that should have surprised me but it did. She looked content. Her face was fuller and her hair was cut short. She told me that she had married a businessman who manufactured something in Pune and that she had two children. She mentioned a few people that we had both known, either to enquire after their wellbeing or to say that she had run into them. Neither of us brought up our work together. As I left, she was talking to Vishal’s son. I was pleased to see that she was still able to bring that tremble to her bottom lip.

* * *

I look at Abhay over the top of my glasses: all of a sudden he is a virtuoso in high drama. In class he often finds it difficult to entice a discernible emotion into his repertoire but today I see a superlative execution of muttering, grimacing and entreating. My tea is sugary and the colour of rust. It is a quarter to four.

It takes some effort but I try to focus on Abhay, even though I am in a damp shirt, seated at a table in this lousy restaurant, waiting for a phone call that will never come. He begins to speak again of the film, news of which is so eagerly being anticipated this afternoon. It involves an airline tycoon, several mistaken identities and a comedy kidnapping. The outdoor shooting schedules have been fixed in the US, South Africa and Thailand. The main lead is the scion of an acting dynasty who is proving to be very popular, despite looking like a lethargic ape. There are a string of heroines, none of whose names I care to remember but all of the same breed: nonentities who enjoy shrieking at their own taut stomachs.

None of my former or current students have enjoyed anything that could be termed a success. One or two may have made it on to a crowd scene in a television serial. These days there are only three feasible routes for actors in Bombay. One needs to be a close relative of powerful industry players; one is foisted on to some unfortunate producer by a criminal with clout; or one possesses incomparable skills in providing sexual favours to the people who matter. Needless to say, I do not spell this out to my apprentices. If they are not able to arrive at these conclusions without assistance, they are even greater imbeciles than I imagined. We will continue with diction and close-up camera skills until they see the light.

She told me that she had married a businessman who manufactured something in Pune and that she had two children… I was pleased to see that she was still able to bring that tremble to her bottom lip.”

It is one minute to four. The call is due any time now. I wonder how long I will be expected to commiserate and fortify. I had planned on drawing the curtains and settling down with a drink this afternoon to watch The Third Man again. It is one of my favourites, an irrefutable classic. Orson Welles brings a special intensity to the character of Harry Lime, adrift in decadent post-war Vienna. I do feel that at one or two points his phrasing becomes sluggish, diminishing the amoral force of the character. But, all in all, a very creditable performance. Notwithstanding the relatively modest screen time, I believe that it was a role I was born to play.

Karwan-e-Hayat (Premankur Atorthy, 1935). Leading lady Rattan Bai was a prototype for sultry Bollywood villainesses and the matriarch of a celebrated film family. Wikimedia Commons” width=”320″ height=”213″>Since the release of my final film, on the professional front my life has been relatively quiet. In the mid-nineties I was cast in a television serial as the family patriarch, a college professor with high ideals. The show bombed. I was told that audiences were unable to accept that I would be the type of man who railed against institutional corruption while monitoring the social lives of his unwed daughters. All appearances to the contrary, it seemed that the image of my character pushing a terrified mother into a pool of lava in Mera Badla (1977) was fresh in the nation’s consciousness. I reacted with grace, shouldered the blame for the show’s failure, and heaped praise on the writers and junior actors, most of whom would not recognise a three-dimensional character even if it ran them down in a BEST bus.

Karwan-e-Hayat (Premankur Atorthy, 1935). Leading lady Rattan Bai was a prototype for sultry Bollywood villainesses and the matriarch of a celebrated film family. Wikimedia Commons” width=”320″ height=”213″>Since the release of my final film, on the professional front my life has been relatively quiet. In the mid-nineties I was cast in a television serial as the family patriarch, a college professor with high ideals. The show bombed. I was told that audiences were unable to accept that I would be the type of man who railed against institutional corruption while monitoring the social lives of his unwed daughters. All appearances to the contrary, it seemed that the image of my character pushing a terrified mother into a pool of lava in Mera Badla (1977) was fresh in the nation’s consciousness. I reacted with grace, shouldered the blame for the show’s failure, and heaped praise on the writers and junior actors, most of whom would not recognise a three-dimensional character even if it ran them down in a BEST bus.

In subsequent years I entered the fray a couple more times, taking on tedious roles in serials with unimpressive runs. In 1999 I appeared on the small screen again in a public service film with an anti-smoking message. I played an obstinate smoker who croaked his regrets from his deathbed, while his family wept around him passionately. After that no narrations I heard suited me, no ideas inspired me. The truth is that Hindi cinema can no longer accommodate the exemplar of a monumental villain. Today the gangsters are all lovable losers, the avaricious industrialists are being feted and, following the economic reforms of Dr Manmohan Singh in the nineties, the smuggler has become extinct.

An actor’s life: the waxing and waning of a particular kind of moon. I am fortunate that in my fecund years I purchased outright a splendid apartment in Andheri. Some twenty years ago, on my mother’s passing, I also inherited her Dadar home. These factors have combined to ensure that I am financially secure and do not need to depend on the good offices of film and television producers for my subsistence. The desire to perform, however, never really retreats.

Abhay is staring at his phone. It is a quarter past four. I am tiring of this game. I appreciate that this is the closest he has ever come to seeing something of worth in his life. He thinks it is a pivotal moment. As he sips his fresh lime soda, I can see that the forces of destiny or whatever he calls it have etched themselves on to his forehead. I motion to a waiter to turn the fan up.

It is twenty past four. I open my mouth to tell Abhay that I have to leave. He interjects first. He apologises and tells me that the call should be coming any time now: of course someone with my experience knows what these film-wallahs are like. He is very sorry for the delay and asks me if I would like another cup of tea. I would not. I decide to give him five more minutes.

I wonder whether he will continue to present himself at producers’ offices tomorrow onwards, memorise dialogue from well-known scenes to perform at auditions, do five hundred press-ups a day. There must be a moment of epiphany even for someone as blinkered as Abhay, a day of violent adjustment, a repositioning towards fitness trainer, salesman or driver. He is still staring at his phone, a bead of sweat settled in his cupid’s bow, willing the call to come. Drilling equipment has been set in motion outside the restaurant – more cacophony to add to this already pitiful scene.

I motion for the bill. Abhay pretends that he did not see and is playing with a string tied around his wrist. The drilling gets louder and then stops.

The phone rings.

Abhay looks at me, terrified. I nod in reassurance. At least I will be able to go home soon. He answers the phone, swinging around in his seat, away from me, his back hunched into the conversation. He says “yes, sir” and “thank you, sir” a few times. I wonder if I will get stuck in any traffic on my way back.

Abhay straightens up and puts the phone down on the table. He has tears in his eyes again.

He has got the part.

He has to report to them on the following day and they will begin settling the details, the signing amount, dates and so forth. The waiter brings the bill.

I give Abhay my hand and congratulate him. I tell him that I have always believed that his capability and dedication would bring him the success he deserves. He is crying openly now. People will think he is my wayward son or a gigolo. I stand up and motion to the door, leaving him to pay the bill.

Outside, I stop a taxi. Abhay emerges and thanks me again for everything that I have done. He insists that he wants to accompany me to my door; it is, he says, his duty. I tell him that it is out of his way, he has much to organise and not to trouble himself. I will be fine, I say.

I get into the taxi and leave.

Even though it is not far, the journey to my place seems endless. The heat is exhausting and my shirt is now soaked. Fumes are everywhere and by the time I get out of the taxi, I have a sore throat. The driver claims he does not have change so I tell him that he will get five rupees less than the fare.

I take the lift to the fifth floor and return to my flat. I pour myself a whisky; some of it sloshes on to my wrist. I slam the freezer door because the ice trays are empty. My drink tastes like warm ash so I push it away. My mobile phone rings. It is Abhay. I ignore it. He sends me a convoluted text message. He has already begun arranging a party to celebrate his role. It will probably be at a hotel in Oshiwara tomorrow evening as he has to leave for Cape Town as soon as his visa is ready. I switch off my phone. As I walk back to the kitchen I see an envelope on the floor, pushed under the front door. I must have missed it when I came in. I pick it up and rip out the card. It is an invitation to the wedding anniversary function of one of the couples who inhabit my building. I tear it into little pieces and then fling them over the balcony. Hands on the balustrade, I watch them as they fall.

From the collection One Point Two Billion.

Mahesh Rao was born and grew up in Nairobi and lives in Mysore. His debut novel The Smoke is Rising won the Tata First Novel Award and was shortlisted for the Shakti Bhatt Prize and the Crossword Award. His stories have been shortlisted for the Bridport Prize, the Commonwealth Short Story Prize, and the Zoetrope: All-Story Short Fiction Contest. His story collection One Point Two Billion is published in paperback by Daunt Books. Read more.

Mahesh Rao was born and grew up in Nairobi and lives in Mysore. His debut novel The Smoke is Rising won the Tata First Novel Award and was shortlisted for the Shakti Bhatt Prize and the Crossword Award. His stories have been shortlisted for the Bridport Prize, the Commonwealth Short Story Prize, and the Zoetrope: All-Story Short Fiction Contest. His story collection One Point Two Billion is published in paperback by Daunt Books. Read more.

maheshrao.info

@mraozing