On Tahrir Square

by Donia Kamal

“Her artistry on the page, translated expertly by Youssef, rings as true as it is enlightening. This book is a bull’s-eye.” Words Without Borders

It was going to be a decisive day, and I was anxious. I put on a thick hoodie, and in my bag I carried a water bottle and, reluctantly, a small onion. I couldn’t call anyone. The “bastards” had cut off all communication. I took a taxi from Zamalek to Heliopolis, where I found my father having breakfast on the balcony. It was still an innocent morning.

“Did you read the paper today?” he asked me.

“No,” I answered. “Is there anything other than the usual garbage?”

He read a few al-Ahram headlines out to me: “Muslim Brotherhood elements call for demonstrations and security forces succeed in foiling the intrigues of the banned group. Cautious calm returns to city streets. Security forces on standby in case of renewed protests. Renewed protests in Suez demand better wages. One hundred million pounds in losses to the municipality due to vandalism, fire, and looting. Freedom of expression is guaranteed. Chaos will not be tolerated.”

I interrupted him. “Baba, tell you what – I’ve heard enough. Go get dressed, or are you not coming with me?”

“OK, OK. I’m getting up.”

It didn’t take my father long to get ready. We stopped a taxi outside the house and headed to Tahrir Square. My father stared out of the car window, and I wished I could read his mind. What did he think of what was happening?

He must have been frightened. His health would not allow him to run if he needed to. But I was not going to let go of his hand; that I was sure of. In all honesty, though, I was terrified. We were facing the Unknown, with a capital U. We had no idea what might happen. There was hardly anyone on the roads except the Central Security forces. The taxi dropped us in Abd al-Moneim Riyad Square. Who were all those burly men? The first scene, not far from us: two of them falling on a skinny young man. I will never forget the sight of that kid under their boots. After beating him senseless, they dragged him to the Central Security van parked under the bridge.

I turned to my father. “That’s it. You’re going home.”

“Oh, you’ve decided for me?” He was driving me mad with his calmness.

“Please, for my sake. It’s only the start of the day, and you can see how it’s going. Tell you what – I’ll take you back to my place. So you’ll be close by, and then you can spend the night with me.”

My father could tell that I was on the verge of hysterics, or maybe he really agreed that his health would not be up to this kind of day. We walked to the bridge and waited for a few minutes for a taxi. I accompanied him to my apartment and made sure he was settled in front of the TV. “Baba, you know where everything is. You can make tea if you want. There’s a chicken in the fridge. Reheat it in the oven when you’re hungry. You need to eat so you can take your medication. I’ll be back tonight. Don’t worry, OK?”

His face was suddenly overtaken with concern. He gripped my arm. “Take care of yourself. I mean it! I couldn’t handle anything happening to you. I only agreed to come back here for your sake. But take care of yourself and don’t be reckless. Run if there’s trouble. Running is sometimes the bravest thing to do, you understand?”

I laughed and hugged him. “Don’t worry about me. I’m a coward anyway.”

“No, you’re not a coward. You can be reckless and unpredictable. But for my sake, you’ll take care of yourself today.”

I smiled as I closed the door behind me and headed back to the Unknown.

My eyes, like millions of eyes that day, were red and swollen because of the tear gas. I looked like I had stepped out of the grave.”

When I got back that night, I was pretty much a wreck, so tired my feet could barely carry me. I was covered in dust, and sticky because of all the soda we’d been pouring on our faces to neutralize the pain of tear gas. My long straight hair somehow managed to look like a toilet brush; it was completely disheveled. My eyes, like millions of eyes that day, were red and swollen because of the tear gas. I looked like I had stepped out of the grave.

My father opened the door. “Where have you been, damn you! I was worried sick!” He pulled me into an anxious hug. “Are you OK? Do you have any injuries? Did something happen to you? Tell me!”

“Baba, just give me a minute to breathe. I can hardly stand. I’ll tell you everything.”

I threw myself onto the small sofa and began to tell my father about the day.

“After I left you I decided not to take a taxi. I walked to the Opera House and into a massive demonstration. I marched with them. The chants were amazing – loud and powerful and full of defiance. Anyway, we got to Qasr al-Nil Bridge. There was constant tear gas, coming from all directions. It nearly blinded me. At first I rubbed my eyes, which made them burn more. The more they burned, though, the angrier I became and the more determined I was to go on. So, we were at the bridge. Then all hell broke loose. If only I knew where they were shooting from. It seemed like the gas canisters were dropping from everywhere. Everywhere. Five or six at a time, the bastards. I couldn’t control where I was going, but was just being carried along with the crowd. Everyone seemed to be pushing in the opposite direction of the bridge. I had no idea what was going on. Were we trying to cross the bridge to get to the square? Were we trying to turn back because there was no way to cross? I couldn’t move. So I breathed in the tear gas and chanted.”

I went on, watching the changing emotions on my father’s face: “Some people were starting to lose it. A boy who looked about eighteen was trying to break one of the lampposts on the bridge. Then someone else stopped him and said that was public property, and the boy broke down crying. By that point, the Central Security cars had blocked both ends of the bridge. I thought that was it. It was obviously a trap. I can’t swim, but thought about jumping into the Nile anyway. All I could think of then was that I could not possibly go on. I was never going to make it to either end of the bridge, and it was blocked anyway, so what was the point? I could hardly see anything. Some kids had started to set fire to the Central Security vans. I won’t lie. I was really scared. I thought the vans would explode once they’d caught fire, and if they exploded, the whole bridge would go up in flames.

All day long we’d been withstanding beatings and tear gas and birdshot… Not to mention the live bullets we could hear throughout the day. It was one long horror movie.”

“Anyway, the vans didn’t explode. But the smoke mixed with the tear gas was so strong. What tipped me over the edge, though, was when some of the boys did not want to let the soldiers out of the vans, and I started screaming, ‘Let them out! Please let them out! We can’t let them die in there!’ It was very dramatic, but the thought had filled me with panic. Those of us who wanted to save the soldiers won in the end, and they let them out. You know, Baba, they were like scared rabbits. They came out with their hands on the backs of their heads like prisoners of war. An escape route was created behind the vans, so that the soldiers could immediately leave the bridge. Otherwise people would have eaten them alive. They’d been shooting at us all day long. All day long we’d been withstanding beatings and tear gas and birdshot, which can cause a lot of damage. Not to mention the live bullets we could hear throughout the day. It was one long horror movie.”

My father asked, “Were you alone all that time?”

“Oh no, I met everyone I know on that bridge. Almost everyone I know was there. But I would see people for a couple of minutes, then lose them. They would run or be pulled away. You don’t get it. It was a massive battle – massive!”

He listened, awed and apprehensive, then said, “I saw things on TV but couldn’t understand what was happening. I had to be out there. I shouldn’t have stayed home like a baby. Fuck this weak health and this weak heart of mine!”

I tried to distract him. “Have you eaten?”

“Yes. What else could I do? I had to take the damn medicine. Go on.”

So I went on: “Once all the vans were burned, things calmed down a little, or that’s what I thought. I left the bridge and met some friends and walked with them toward the square. The sun was setting. Something odd was going on. The security forces were almost nowhere to be seen. The sky was filled with smoke. People were still chanting, and I’ll tell you something – at one point I was leading the chant. People chanted after me, even though my voice was high-pitched and silly.

“I didn’t get to the square in the end. Smoke was coming out of the big building on the corniche, Mubarak’s party headquarters. It was on fire. People were running out of it carrying stuff. I was on the other side of the road. I could hardly stand, but couldn’t walk either. People were carrying chairs, computers, documents, and desk lamps out of the building. Just random stuff.

“And all around me on the street, people made predictions: a curfew, a presidential speech, and all sorts of other things. But I panicked when they said the army was deployed. I mean, shit, the army! Were they going to shoot at us out of tanks now?”

“Yes, I saw the tanks and armored vehicles on TV. My heart nearly stopped.”

“Keep that evil thought away,” I said, waving away the bad omen. “I wanted to run, you know. I mean, Central Security vans and guards and officers – we can handle those. But the army! I had only ever seen armored vehicles at the Sixth of October Museum! Anyway, for some reason people decided to deal with the situation like it was a wedding or a mulid festival. They started running toward the tanks, climbing on top of them, hugging the army soldiers, and chanting for them! I didn’t really get it, but my feeling was that people were so scared and tired they decided to embarrass the army into friendliness!”

I was close to him when he fell, and it was no stray bullet that hit him. I did not want to touch him. I did not want to touch the blood. But he almost fell into my arms. He was already dead.”

The TV droned on with the news as I told my story. I was quiet for a few moments, then realized I didn’t have the strength to tell any more. I had seen a lot of blood that day. I didn’t share all the details with my father. I didn’t tell him about the boy’s blood that, while a bit fainter now, still stained my clothes. I was close to him when he fell, and it was no stray bullet that hit him. I did not want to touch him. I did not want to touch the blood. But he almost fell into my arms. He was already dead. The bullet had gotten him in the chest, in the heart, I’m not sure, but he died immediately. His blood was on my clothes. That was all I worried about. My heart was beating all over the place. A bystander had lifted me off him, shouting, “The boy’s dead! The boy’s dead, you dogs!”

This wasn’t the first dead boy, but he was the first whose blood stained me. I crawled away on my hands and knees and stood up at the edge of the crowd. I visualized throwing myself into the river, but I didn’t do it. I had to get back to my father. I had to tell him what I had seen and reassure him that I was OK.

I didn’t throw myself off. Maybe I should have. But I didn’t.

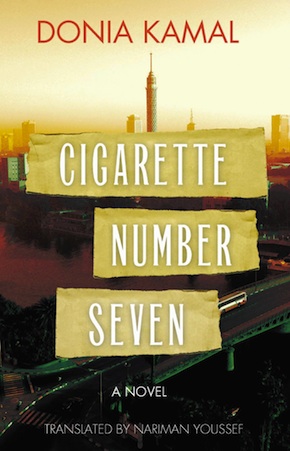

from Cigarette Number Seven (Hoopoe, £9.99)

Donia Kamal is an Egyptian novelist and producer. She has produced more than fifty documentary films and numerous television shows for various Arab networks. She currently lives between Egypt and the UAE. Cigarette Number Seven, her second novel, is out now in paperback from Hoopoe, an imprint of the American University in Cairo Press, translated by Nariman Youssef.

Donia Kamal is an Egyptian novelist and producer. She has produced more than fifty documentary films and numerous television shows for various Arab networks. She currently lives between Egypt and the UAE. Cigarette Number Seven, her second novel, is out now in paperback from Hoopoe, an imprint of the American University in Cairo Press, translated by Nariman Youssef.

Read more

@DoniaKamal

Nariman Youssef is an Egyptian translator and researcher working primarily in Arabic and English. She currently lives in London, where she is partly based at the British Library.

@nariology