The Komagata Maru incident

by Shahnaz Habib

The colorful history of the Western passport does not account entirely for passportism against Third World countries. For the crucial piece of subtext missing in this history, we have to read between the lines. In the nineteenth century, the British had made it a common practice to move around indentured labor between their colonies. However, when its colonized people started using their status as Commonwealth subjects to move around of their own free will, the British government realized the dangers posed by this open-door policy. In her brilliant book Indian Migration and Empire: A Colonial Genealogy of the Modern State, Radhika Mongia writes about how the migration of about two thousand Sikh men to Canada in 1905 prompted a long chain of pearl-clutching correspondence. The men had “doubtless come under misrepresentation as they are not suited to the climate, and there is not sufficient field for their employment. Many are in danger of becoming public charge and are subject to deportation under the law of Canada,” the governor general of Canada telegrammed to the secretary of state for the colonies in London. This concern trolling would prove to be unfounded: by 1907, all but fifty to sixty of the men had found employment. It’s also safe to assume that they managed to find appropriate winter clothing and kept themselves warm.

But as Mongia notes, this unprecedented migration created an interesting administrative conundrum for the empire upon which the sun was not supposed to set: “how to distinguish between British subjects, members of a single expansionist state, without calling the entire edifice of the empire into question.” How does one prevent colonized people from moving freely through the colonies without striking an obviously racist-colonial stance?

Working together, the governor general of Canada (whose goal was to safeguard Canada’s whiteness), the secretary of state for the colonies in London (whose goal was to keep the empire strong), and the British government in India (whose goal was to pretend that Indian colonialism was a force of good) came up with an elaborate scheme that involved, among other rules, a policy that only travelers on continuous journeys from their port of origin would be allowed to enter Canada. Since there were no shipping companies plying nonstop between India and Vancouver, this effectively halted immigration from India.

Problem solved until 1914. On May 23, 1914, the Komagata Maru arrived off the coast of Vancouver carrying 376 passengers, mostly Sikhs. Hired by Sardar Gurdit Singh, an Indian entrepreneur with sympathies to the Ghadar movement (a diasporic political movement to overthrow British rule in India), the Komagata Maru had artfully managed to fulfill the continuous-journey requirement by having its Indian passengers board the ship in Hong Kong and Shanghai and Yokohama, from the Indian diasporas located there.

The passengers sat half a mile from the Canadian shore, starving and harassed, while the former prime minister declared in Parliament: ‘The people of Canada want to have a white country.’”

All the storms that the Komagata Maru encountered on the high seas could not have prepared it for the storm of racist outrage unleashed against it as it sat for two months in the Vancouver harbor. Not only were the passengers not allowed to disembark; a military launch patrolled the ship constantly to ensure that it could not even dock. The local South Asian community advocated fiercely for the ship’s passengers and raised money to keep paying the charter fees that became due since the ship did not return to its owners. But they were not allowed to help the passengers, who rapidly ran out of food and sat half a mile from the Canadian shore, starving and harassed, while the former prime minister, Wilfrid Laurier, now in the opposition, declared in the Canadian Parliament: “The people of Canada want to have a white country.”

After two months, the Komagata Maru was forced to sail back to India. It was escorted out of the Vancouver harbor by the Canadian Navy, prepared to shoot, and it was met in Calcutta by the British Army, who declared the ship full of insurgents and shot and killed twenty passengers.

The Komagata Maru incident had revealed the hollowness of the continuous-journey regulation, and once again the question remained. How to prevent brown people, armed with the juridical definition of themselves as equal subjects of a huge empire, from moving into white countries? The problem was that the colonial government in India could not be seen to be obviously racist. There was a difference between shooting at “insurgents” and denying migration outright on the basis of skin color. So much had been invested in the propaganda of the British as just rulers, bringing fairness and equality to the tropics. Besides, the anticolonial movement in India was gathering strength, and the last thing the colonial government wanted to do was feed that fire.

The solution reached was to establish a passport system for Indians. This British Indian passport would entitle a traveler to admission anywhere in the colonies. But the number of these permits or passports would be limited. And it became a criminal offense to embark on a journey from any port in British India without a passport.

This is the useful paradox of the passport as a form of control. The passport would entitle, but the limited number of passports would disentitle. In one stroke, the seeming granting of a privilege would actually be the mechanism that took away a privilege that was freely available, at least theoretically, until then.

Luckily, the First World War was underway, and passport regulation was easily established under the aegis of security theater. The rules requiring passports from all Indians traveling outside India appear as the Defense of India (Passport) Rules. But, as Radhika Mongia points out, these were actually the Defense of a White Canada Rules. Not only did the passport allow the empire to absolve itself of racial motivations; it also permitted the exploitation of “security” as a potential realm for controlling the audacity of migration, and it consolidated the power of the empire as the sovereign authority that gets to decide who gets to travel. A passport is a pretty convenient thing to have – if you are a state.

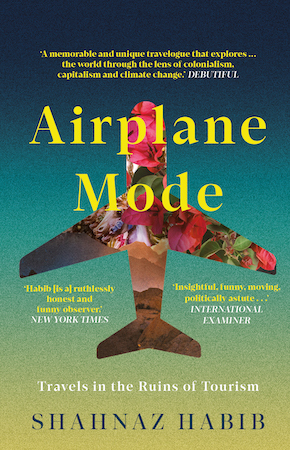

from Airplane Mode (September Publishing, £12.99)

—

Shahnaz Habib is a writer and translator based in Brooklyn. She translates from her mother tongue, the south Indian language of Malayalam, and has translated two novels by Benyamin, Jasmine Days, winner of the 2018 JCB Prize, and Al Arabian Novel Factory. Airplane Mode, her first book, was longlisted for the Andrew Carnegie Medal of Excellence in Nonfiction, and is published as a Paperback Original by September Publishing.

Read more

shahnazhabib.com

@mixedmsgs

@septemberbooks

Author photo by Eva Garmendia