The legend of Mawther Meg

by Edward Carey

Sometime in the fourteenth century (during the time of Julian the anchorite), Norwich was overcome by a great plague of beetles. The beetles, which are especially common in the flat, damp lands of East Anglia, are larger in this part of the world. An ordinary deathwatch beetle grows up to a half inch in length, but here East Anglian deathwatches have been known to reach near two inches. And these beetles threatened to devour the city, which was then mostly made of wood. All was nearly lost, it is said, and would have been entirely, were it not for a woman named Meg Utting.

She had ever been strange and obscure, this Meg; some said she was mad, others that she was evil, but most of all people said she was very hungry. A poor, unmarried woman, and such people can be especially unlucky. Only her sister would speak to her, and that sister would give her half her meagre victuals and so kept them both alive. But now she was about to become our city’s saviour, for Meg Utting had contrived a way of collecting the beetles. One afternoon, in her despair, knocking her head against the oak beam of her hearth, she noticed beetles come rushing out; she crushed them underfoot. In her curiosity, she banged her head once more, and yet more beetles came. By this action, unbeknownst to her, she was simulating the reverberations of some primal beetle mating call, and thereby she brought beetles in swarms to her house. The more she banged her head against the beam, creating a rhythmic thump, the more the beetles rushed toward her. The streets around her home, Fishergate Street, Peacock Street, and Cowgate Street, became so thick with beetles that it was as though a strange muddy river were flowing toward her in a terrible hurry, until the waves broke at the house of Meg Utting.

The best way of demolishing the pest, Meg discovered, was to cook it. She had a great pot on her stove, and when it filled with beetles – by now they were dropping from the ceiling – she let them simmer and boil. What I find most extraordinary about this story, however, is what happened next: somehow, Meg discovered that the cooked beetles, all mixed together, had a taste that was quite marvellous.

Meg Utting began to sell her beetle jam, as she called it then, and soon all of Norwich came to eat it. She made a small fortune from it, in time, and even married a man much younger than herself, a freeman of the city. She had a sister, Meg did, as already mentioned, but it is said that she never helped her sister when she came asking, and the sister died in poverty and of starvation. But that sister’s last words, it is said, were to curse Meg, and to proclaim that one day a child would come into her life and that child would be the death of her. “Maybe today, maybe tomorrow, maybe not for many a year, but the child shall come, and that shall mean your end.”

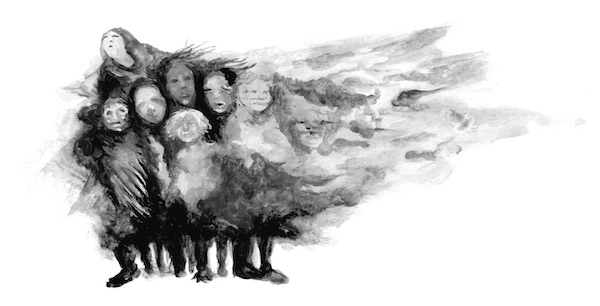

It was around this time that the children of Norwich first started disappearing. Some people muttered that Mawther Meg had eaten them or drowned them in the Beetle Spread.”

Eventually – it may have been from all the knocking of the head against the beam, or perhaps some of the beetles had got inside her head – Meg Utting went mad. She was seen about the streets, crying out, threatening the children. She came to be mockingly called Mawther Meg, mawther being our local, mostly ill-meant word for girl or woman; also, our Norfolk word for scarecrow is mawkin, and I have often felt these words and their meanings – the beetle woman and the bird scarer – must be related. This name was often reduced, further, to Maw Meg.

It was around this time that the children of Norwich first started disappearing. Some people muttered that Mawther Meg had eaten them or drowned them in the Beetle Spread. That people were eating their own children now on buttered bread. Some mused that she was an ancient, evil spirit come up from hell; others that she had mated with a great beetle devil that lived in the nearby Thorpe marshes. Whatever the truth, Meg Utting grew thinner and thinner, despite all the Beetle Spread, until she appeared the physical embodiment of Hunger itself.

It is certain that from this date the children of Norwich started to be lost in large numbers.

When a child disappeared, the reason given for it was the legend of Maw Meg. Crowds of Norwich hid behind the terrible story. Be careful or Maw Meg will get you, they warned, and it was a great game – but also, you see, a child did go missing and was never found.

Who the real Maw Meg was cannot now be known. But what is certain is that she gave us the Spread, and the making of it became a great business, and we have had it here with us ever since. Every jar of Beetle Spread, even now, is said to contain at least one deathwatch beetle. There is a statue of Meg near the Erpingham Gate of Norwich Cathedral (named after Sir Thomas Erpingham, who led the archers at the Battle of Agincourt), and beside her is a statue of our other great Norfolk hero, Horatio Nelson, who went to the Norwich School nearby. People who come to Norwich, I am told, most often head to see the statue of Maw Meg Utting; indeed it is a custom to touch one or two of the bronze beetles at the statue’s feet. Touching these beetles is supposed to bring you good health (likewise the Spread), and so the statue of Meg Utting is much more touched than the one of Horatio Nelson, for touching Horatio Nelson is not supposed to do you any good at all, and may even diminish your person – the admiral’s statue having but one arm.

In my bedroom is my typewriter table and upon it is my seaweed-coloured typewriter. It is like a building, this machine. Like a parliament or opera house upon my table. Father gave it to me. It is very modern. It came up from London in its own crate and says in golden letters THE ENGLISH STANDARD TYPEWRITER, 2 LEADENHALL ST., LONDON EC. It is not a children’s object, but beside it I have a toy model of HMS Victory. Like many a Norwich child, I also keep close at hand the toy variously called the Beetle Rattle or the Deathwatch Dummy or the Beetle Clacker, sometimes just called the Meg Peg. It is, as you probably know, two wooden spoons bound together with leather straps, bowl against bowl; you pull back one spoon from the other, stretching the leather, and then let it go so that it makes a loud clack that is supposed to replicate the noise of a deathwatch beetle. The toy is supposed to summon beetles. I myself have never had much luck with it and consider it a dull enough project. But I do hear, sometimes, the noise of the Meg Pegs as the Norwich children play in the park.

The smell of the Spread is hard to explain to the uninitiated. It is like a concentrate of meats. It is like a new animal not yet named. It is like a strange and uninvited intimacy.”

Forgive me: I was talking of the Spread. Every one of the jars says UTTING’S BEETLE SPREAD and in slightly smaller letters of norwich. People of Norwich (and many who are not) eat Beetle Spread on toast or cheese or fruit or chicken or ham or bacon, or place a spoon of it in a mug of hot water and drink it in the winter. It is a most versatile substance, said to be beneficial against most ailments. In the summer, also, if spread on strips of paper, it can catch flies.

We of Norwich are very proud of Beetle Spread. Here, where the Spread is made, the air itself is often spread with it. Sometimes the city may fall under a dark and ruddy fog, caused by an accident at the factory, when some quantity of Spread has become airborne. On such occasions we all go inside (I don’t mean me of course, for I’ve never left) and wait for the cloud to pass. Afterward, we wipe our windows with newspapers (I don’t mean me of course), and the newspapers always come away red. Have I mentioned that Beetle Spread is red? Oh, but surely you’ll know that. It has been red for centuries, though originally it was black or brown. It is red now because at some point, no one can say exactly when, madder root was added to the ingredients. We have much madder root in our Norfolk and have for a long time used it in our dyeing of clothes – hence the famous red Norwich shawl – and hence the square of the city called the Maddermarket, which is where they sell the root. At one time our River Wensum ran red because of the dyeing of materials, and today it runs red on account of excess Beetle Spread as it flows from the factory. I cannot see the River Wensum, I have indeed never seen it, but I know it is there, for I have been told about it often enough, and I do believe it is a truth that if I got into the Wensum and swum (I cannot swim), getting very red I suppose at first but then less and less so, I would arrive at last to a place called Great Yarmouth. But I don’t go swimming to any (Yare) mouth great or small, I stay here inside the bounds of Theatre Street, Chapelfield East, Chantry Road, and Assembly House.

Here in the theatre, if we are low on pins or spirit gum, we have often been known to fix our wigs or beards with a little Beetle Spread. One of the disadvantages of the Spread is that people can roll a small ball of it and pop it in their mouths and then chew it for hours (making their teeth red – oh, the red teeth of Norwich!) and then, inevitably, after a time, after the taste has gone or jaw ache has set in, they often spit it out, on the street or even upon our front-of-house carpets (which are red in colour because of the Spread, in the hopes of disguising it). Cleaning up after Beetle Spread gum is a time-consuming business. The smell of the Spread is hard to explain to the uninitiated. It is like a concentrate of meats. It is like a new animal not yet named. It is like a strange and uninvited intimacy.

Something else about Beetle Spread: I think the missing children are inside it.

I know this was alluded to before, but then it was said in jest and to frit the Norwich slums. But I think it is true. I came to this one morning as I sat propped up by pillows in my sickbed, studying the Norwich lost. A piece of toast beside me with butter and Spread. I read about the lost children, I took a bite of toast. Ernest Ridings I read, and I took a bite of toast. Bess Tollymash I read, and I took a bite of toast. Susie Headley I read, and I took a bite of toast. And then I stopped. I dropped the toast, it fell Spread-side down upon my sheets, a great red mark there.

Oh!

I no longer eat the Beetle Spread. I will not have it near me.

from Edith Holler (Gallic Books, £16.99)

Illustrations by Edward Carey

—

Edward Carey was born in North Walsham, Norfolk and now teaches at the University of Texas at Austin. A novelist, visual artist, playwright and director, he is the author of the novels Little, which was a Times and Sunday Times book of the year, The Swallowed Man, the YA series The Iremonger Trilogy, and the collection of lockdown drawings B: A Year in Plagues and Pencils. Edith Holler is published by Gallic Books in hardback and eBook.

Read more

edwardcareyauthor.com

@EdwardCarey70

edwardcareyauthor

@gallicbooks

Author photo by Elizabeth McCracken