The man who spoke with butterflies

by Ivica Prtenjača

In the end, what does it matter who developed the photo? Why am I sifting through a time so far away, a moment that has already frozen and petrified, like a snail fossil in a stone among the billions of other stones that line the shore? I’d like to say a word in my defence, but at the same time, I don’t. I want to cherish every second that remains to us, that’s what I want to tell you when I see the duty nurse posting a notice on the door to the corridor leading to your room, banning patient visits because of the pandemic. Do you even know anything about Covid-19, that terrifying new word that now separates us? That has erected a wall between us at the very time when we should be tearing all our old walls down. When the only thing that matters now is the love we have for each other, the love we can show each other in the time left to steal.

‘I’m going to bed,’ says my mother. ‘I’ll take a taxi up in the morning, and when you come home from work, we can head back up together.’

‘I don’t know if they’ll let you in,’ I say.

‘I have to go, you that know that, I’ll ask for five minutes with him, just five minutes. I’m going to ring him now, see if he’s asleep.’

She went to her room and closed the door, but I see her, I can see the whole thing. She’s hunched over, mobile phone pressed to her ear, and when he picks up at the other end, she speaks loudly and slowly, over-enunciating. So he gets the message, so he understands that we’re going to try and come and see him, that we’re going to take him home, that we’re going to save his life, which can’t be saved. He tries to reply through the mask, but his words barely carry to her. She listens to the squeaky whistle of air, him saying something she can’t understand. At least we managed to hear each other’s voices, that’s what she’ll say later.

Two shots ring out in the night and give me the fright of my life. Then I realise that it’s just someone celebrating a Croatian goal in a friendly against Lithuania. You’d have to be a fucking dick to pull out a pistol when a ball rolls into a net. But that’s clearly a minority view, because others in the neighbourhood respond with firecrackers and cheers. We quiet folk, we just keep quiet. Our team’s leading, they’re playing superbly, they’re going to win. We’ve got nothing to complain about.

As a child, I’d spend hours flicking through our photos, but I’d always pause at this one, an image of happiness itself, a man who is calm, collected, silent and happy.”

Jole Rocket grew old in Canada. He’s out there on his glazed porch waiting to die, no chance of ever giving it both barrels, which was his phrase for firing a shotgun. Boom boom. But if he were here now, he’d definitely reply, the dipshit to whom I owe so much. His passion for shooting created this photo, but I still don’t understand why he took it. What did he see in the man leaning on the bonnet of a second-hand Fiat, hair parted to the side, a digital Seiko on his wrist? Why did the man gaze so happily towards the Pentax, and how is it, that at that very moment, a dipshit like Jole managed to press the shutter and create an image like this? As a child, I’d spend hours flicking through our photos, but I’d always pause at this one, an image of happiness itself, a man who is calm, collected, silent and happy. It’s extraordinary, the role crazy Jole Rocket played in our lives, at least in mine, and at least tonight.

They’ve started to restrain him so he doesn’t get out of bed and take the mask off, and then fall and hurt himself due to a lack of oxygen. ‘Why don’t they give him something to help him sleep?’ I asked the nurse as she passed me in the corridor today.

‘You’d have to ask the doctor,’ she said, gently fobbing me off.

I asked the first doctor I met on the ward.

‘We can’t, he’s weak.’

‘You don’t think he’ll wake up,’ I said, staring at her, not expecting an answer.

She just shrugged her shoulders and kept walking. At that moment, every bone and muscle in my body went limp and my temples started to pound. Yes, that’s all I needed to know. The torment. The hopelessness.

Is he sleeping, is he lying there having spasms, what’s he thinking about?

I was again twelve years old when I set off to bring our horse and cow in from the back meadow. They’re chained to steel posts driven deep into the ground, and I need to bring them home, water them, and milk the cow. My father wants to come along. Let’s go for a walk, he says. I’m confused, because when we’re together, we do real jobs, like concreting and stuff, we don’t do easy stuff like going for walks. Never. Even when my brother and I go for a swim, we run the hundred metres or so from the car to the beach by ourselves. I’d never been for a walk with my father, this was the first time. I remember a few of the things we talked about. I asked him what the path we were on looked like when he was a boy. It was a forest, he said, full of rabbits and partridges. As we walk, the sun falls behind us, sinking down beneath the cypresses next to the church, the dappled light filtering through their darkness, the odd ray dancing along the rough surface of the trunk, bringing another summer’s day to a silent close. But until that happens, in the gloaming, as a golden glow streams out over the fields and vineyards, as we bask in the gentle warmth on the backs of our necks, and little dust clouds rise at our feet, the day isn’t yet done. There’s enough time to bring the animals home before first dark, when the woman who brings her bottles to buy milk from my grandma will arrive.

We soon came out onto a long, broad meadow. The cow was chewing its cud, the horse still grazing, lifting and then lowering its head as it saw us, monumental and white like a sculpture, only the thinnest of chains around its powerful neck and thick, almost mustard-coloured mane. Both animals are so calm, so harmless. Dad untied the cow, and she waddled over to a patch of grass she hadn’t been able to reach. I untied the horse, and he tore off, rearing up on his hind legs in unbridled joy. As we strolled across the dry grass as if it were carpet, my father first knelt down, and then lay on his stomach. I did the same, our foreheads almost touching.

This man of thirty-seven, a master baker and house builder, then patted the grass with his open palm, and butterflies and gnats soon took flight. Then he did the same with his other hand. And then I did it, and then him again, smiling, radiant. He only said: ‘Gorgeous, isn’t it? What more could one want?’ Just the butterflies in a field at dusk, just the butterflies and their quiet, eternal hum.

But I couldn’t speak, I could only lie there soaking up this sudden intimacy, the horse standing over me as I rolled onto my back. From below, I stared up at the under side of his belly, neck and head. He bent down a little, looked me in the eye, snorted, and walked off.

‘Shall we go,’ my father said, bringing me back into the world. He’d already pulled out the stakes, bundled up the chain, and hidden them in a thorn bush next to the sledgehammer I’d use again tomorrow. We walked slowly, trailing behind the horse and cow, both still so calm as the sun made its way around the cypresses. At the edge of the meadow, I clambered up onto a dry stone wall and mounted the horse. My father took a few quick strides, grabbed its mane, and leapt up in front of me onto the horse’s back, like an Indian. We rode slowly, following the cow as it ambled down the shadowy path.

There’s no time for collecting memories anymore, the sediment has broken the bottle, and fresh soil now lies piled ready next to my father, the man who spoke with butterflies I didn’t even know existed.”

Covered in sweat, I turned over in bed. I got up, stood at the window, and gazed out at the headlights, an enormous billboard flashing on the roof of the building next door. Should I tell him all this tomorrow? That I remember? Or would that be wrong? There’s no time for collecting memories anymore, the sediment has broken the bottle, and fresh soil now lies piled ready next to my father, the man who spoke with butterflies I didn’t even know existed.

I’m going to get my phone and search up anything I can find about flour causing lung disease. It’s haunting me. My whole life long, I’ve never touched anything softer than flour.

Is it even possible, or was the doctor just making up stories, hoping to impress his colleague and the nurse. Or does the mighty hand of death lurk in that fine grind, the hand that first pressed on my father’s lungs a few years ago, deciding to regulate his oxygen here on earth. Did the flour really do it? Or was it fate? Is he sleeping? Is his night restful? I’m afraid of the answer to that question.

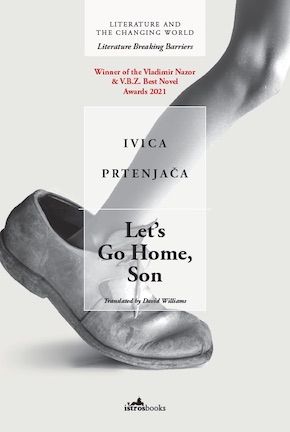

from Let’s Go Home, Son, translated by David Williams (Istros Books, £12.99)

—

Ivica Prtenjača graduated from the Faculty of Education in Rijeka and is a publisher and prominent promoter of literature on Croatian Radio. Having published a number of poetry collections, and twice been awarded the Kiklop Prize for poetry book of the year, he made his prose debut in 2006 with the novel It’s Good, It’s Nice. In 2014, his novel The Hill was awarded the V.B.Z. and Tisak Media award for best unpublished novel, which he won again in 2021 for Let’s Go Home, Son. He lives and works in Zagreb. Let’s Go Home, Son, translated by David Williams, is published by Istros Books in paperback and eBook.

Read more

instagram.com/ivicaprtenjaca

@Istros_books

Author photo by Tanja Dabo

David Williams holds a PhD in Comparative Literature from the University of Auckland. He has taught at the Universities of East Sarajevo, Belgrade, Novi Sad and Auckland, and was a postdoctoral fellow at the Leipzig Centre for the History and Culture of East-Central Europe and the University of Konstanz. He is the author of Writing Postcommunism: Towards a Literature of the East European Ruins (2013), and the translator of Dubravka Ugrešić’s Karaoke Culture (2011) and Europe in Sepia (2014), and of Miljenko Jergović’s Mama Leone (2013). He lives on the west coast of New Zealand.

auckland.academia.edu/DavidWilliams