Thoughts from/on the frontier

by Bruce Omar Yates

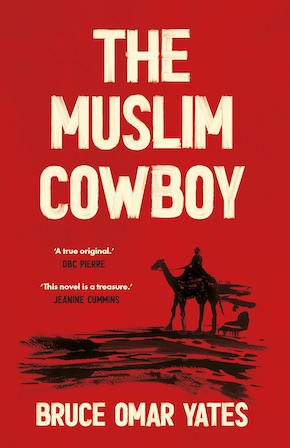

A ‘frontier’ is a place where one society meets another. A place of risk and encounter, where one wilderness sees itself change into something ever wilder. The historic American West might be the archetype of this idea of a frontier; the most famous of belts between the known and unknown where opportunity, change, exploration and exploitation coexist beyond sightlines. And so, it might define others we know. My book The Muslim Cowboy, a Middle Eastern Western about an Iraqi man entranced by old Western movies, who dresses in double denim and roams a lawless landscape in search of his own Western story, draws parallels between the American West and post-war Iraq, casting that setting as a frontier in turn.

As two frontiers together, the Wild West shares many uncanny equivalences with post-war Iraq. Of course they are superficially similar, both having vast, desert landscapes where freedom and isolation are bound together, but beyond that there’s also the sense of established laws and societal structures being either absent or in flux, creating a place where individuals have to rely on their wits and a personal moral code in order to survive. Perhaps because of that, there are other incredible and almost trope-like similarities between the two. Post-war Iraq has US wanted posters of terrorists on the walls of tea houses as though they are the Western saloons we’ve already seen; various factions of Sunni and Shia militia roam the desert as if Union and Confederate units in turn. You’ll find bandit gangs holding up trains. The Chinese government is even taking advantage of the mess to move in and build a railway, evoking the Chinese railroad labourers seen in typical American Western settings.

Looking at post-war Iraq through the lens of the Western, we are familiar with the violence, the tropes, the bravery, the hope. We can empathise with a character who is our other, and ally ourselves instantly with their story. At the same time, and suddenly, we have complete comprehension of the state of their setting and what it should imply – the aforementioned risk and encounter, exploration and exploitation. By examining the parallels between such places, we gain a deeper understanding of the experiences of their people. But the concept of the frontier extends beyond the geographical.

By applying the deeply ingrained narratives of the old American frontier to new places, fiction helps us relate to the human experience of them on a deeply personal level.”

The titular character of The Muslim Cowboy embodies a different kind of frontier. He exists in oscillation of the space between Muslim and cowboy, as though mixed-race of canon or custom. Within him too is the opportunity for expansion and change. We realise that the frontier can also be found metaphysically, on the plane of uncertain circumstance, created by the confusion of some psychic or social condition or another. This shift in understanding invites us to explore the inner landscapes of individuals, even of societies. We live more and more in a strange postmodern situation where truths and traditions are blended or reinvented. Frontiers are no longer remote abstractions, but cerebral, daily realities for all of us, in the metropolis or otherwise.

The most fluorescent frontier of my book is perhaps that which comes to life in the writing of the reality into romance; found in the space between the reality of the conflict and its iteration on the page. This frontier is where the raw and brutal truth of the horrible human experience might be transformed into something that can be understood, empathised with, and processed. We can discuss how art might be a mirror to the world or interpret an issue or event, but where tragedy is involved, perhaps art is most functional as a framework for facing it. I often think the newly globalised world is itself a frontier entirely. Where in history there was a general migration to the American West in search of opportunity and affluence, there are now vast global migration patterns carrying people through strange and uncertain landscapes. The risks and rewards of making a new life abroad in the modern world are as pronounced as they were in the Wild West. The human stories we tell of modern migrants will also imply the metaphysical frontier between reality and fiction, and will transfigure those tragedies so we can bring ourselves to experience them in turn too.

In the frontier, oscillation is understanding, and pursuit is transformation. By applying the deeply ingrained narratives of the old American frontier to new places, fiction helps us relate to the human experience of them on a deeply personal level. These narratives not only reflect our current realities, both physical and metaphysical, but also shape our perception of how we might (and what it might mean to) navigate them with all their uncertainty. In oscillation, in some brief moments, we might bridge the gap between a familiar past and an unpredictable present. Doing so, we might grow more certain of the truth, and we might grow more confident in facing the future.

—

Bruce Omar Yates was born in London to an Indian mother and an English father. He grew up in the south of France before returning to London to study Literature and Film at King’s College. He was principal songwriter in the rock groups Famy, who released their album We Fam Econo in 2014, and Los Porcos, who released their album Porco Mio in 2016. The Muslim Cowboy, his first novel, is published by Dead Ink Books.

Read more

instagram.com/bruceomaryates

@deadinkbooks