Under the circumstances

by Marni Appleton

SWEET AIR, DIVINE LIGHT! How long have we waited for this happy sight? This ancient city, its sun-baked streets, the Acropolis in the distance, raging with light. We are here, so it begins.

The first night. Everybody orders wine. It comes in little jugs called carafes. Red or white, it doesn’t matter. We simply ask for krasí, and later ouzo. We say parakaló too, when we remember. The bartender tells us we shouldn’t do shots. Ouzo is to sip slowly, he tells us. We nod, but when he turns his back, we down it anyway. The drink is cloudy-white and smells medicinal. Sophie holds off the longest, sniffing her glass suspiciously for several minutes. When she finally takes a sip, she screws up her face and gasps. We cheer. The boys laugh. The bartender rolls his eyes and mutters something to a customer. We know we are being ridiculous, but we don’t care. We are here, finally, and everything is as we imagined. We smoke cheap cigarettes from crushed packets. We try shisha. We hear the summer breeze shushing through the cypress boughs, the crackle of ancient history alive in the air. The boys tell us the ouzo will crystallize in our stomachs and that when we drink water in the morning we will become drunk again. This seems entirely possible. Everything seems possible. We could turn objects to gold with one touch, flap our way into the sky, towards the brightness of the sun. Around 1 a.m., the teachers urge us back to the hotel and we go, stumbling, laughing – about what, who knows, who can remember? One of the teachers says the first night is always a bit bacchanalian. We laugh at his choice of word; we get the reference.

All hail Dionysus! we shout.

We should make a sacrifice, Nico says.

I’ll kill your firstborn daughter, Leo calls back.

We erupt.

When we get back to the hotel, some of us head to the bar, but the vibe is not what we had hoped for: tinkling piano music, low lighting. The drinks are expensive. The single, besuited bartender regards us without a smile. Our enthusiasm wanes. We head upstairs. Some of us stumble to bed, while others continue drinking from bottles of wine stashed at the backs of wardrobes, under beds.

All hail Dionysus! Anwar shouts, alone, on the stairs.

No one responds. The silence tells him it’s time to go to bed.

—

We wake early the next morning, the sun poking its insistent fingers through the cracks in the hotel curtains. We have so much to do, so much to see! The teachers tell us the schedule earnestly – No dilly-dallying please, we’ve got a very busy day! We have studied hard, written essays, debated, taken exams, and now, finally, this is our reward. We will walk in the footsteps of Plato, Aristotle, Socrates, in the shadow of the Olympian gods.

But first, Nico tells us about how he vomited in the shower. It was properly projectile, he says. Like a fountain.

Gross, says Katy.

I feel fine now though, Nico says. And I drank almost a litre of water this morning and haven’t got drunk again, so thank god for that.

The ouzo is just dissolving. You’ll be sloshed in half an hour, says Anwar.

I’ve got a headache, Leo whines. I need a paracetamol.

Sophie rubs his back. You boys! You never know when to stop.

We chatter as we load up our plates at the buffet: yoghurts, sweet pastries, olives, bread, cheese, boiled eggs cut in half like happy yellow suns. The floor-to-ceiling windows are thrown open to the bright morning. A soundtrack of city sounds, beeping horns and busy breakfast clatter. The stories keep coming. Who else was sick? Who passed out? Who fell over on their way back to the hotel? One of our group is missing – Molly. She tiptoed into our room, quietly quietly, as the day was breaking, the stars shrunk, the night almost nothing, hair matted around her face. Where is she now? When we all left for breakfast, she was still in the shower, washing herself over and over. Maybe she’s sick. Maybe she’s still drunk.

Downstairs, in the hustle and bustle of the restaurant, we are having fun. We forget Molly. Wait, who danced in the street? Who said what to which teacher? We laugh and laugh and laugh.

—

On the third day we leave Athens, sunburned and exhausted, to board the cruise ship. It is another glorious day, the sea smooth and shiny like crushed silk. Our ship is called Antigone. We are disappointed; we haven’t learned the tragedies yet. Our set text for this year is The Odyssey. We would have preferred to board the other ship in the cruise company’s fleet, Scylla, but that ship sails in the wrong direction, west around the jagged coast of mainland Greece and on towards Italy. We love the tale of Scylla, the beautiful nymph turned man-eating monster, and Circe, the witch-goddess who transformed her enemies into pigs.

There is a photo of us lined up in front of the cruise ship, the only photo Molly is in. A row of girls, all smiles. The luminous colours of clothes that have not yet been washed, the false shop sheen shimmering in the sun. One of the teachers counted us down: three, two, one, smile! We all smiled. Molly did too, wide-lipped, full of teeth. Later, we looked at that smile and asked: how could she? How could she smile, after what she’d done? Back then we thought nothing of it, the way she did as she was told and floated along with us throughout the day, like debris on the surface of the sea. Later we cropped her out so only her arm remained, strung up in thin air like a dead thing.

Are you all right/what’s wrong/everything okay? we ask, words overlapping. She’s been acting strange all day. We call to her – Molly! – but she doesn’t look back.”

In the room, the narrow room with three sets of bunk beds and not enough space to move, we ask Molly if she is all right. She says she is fine, just tired. She doesn’t unpack her bag. She leaves it on the neatly made bed and goes for a walk alone on the deck, her hair whipping her face in the wind. She looks out to sea, the great expanse of water that now lies between us and the mainland, a million miles away.

At dinner, we sit at a round table. Pressed white tablecloth, moussaka. A terrible combination. Halfway through the meal, Leo sidles up, wanting to talk to Sophie. In private. She smiles and excuses herself. On the other side of the table, Molly drops her cutlery and pushes her chair back with a screech. Her food, barely touched, abandoned. Are you all right/what’s wrong/everything okay? we ask, words overlapping. She’s been acting strange all day. We call to her – Molly! – but she doesn’t look back. She rushes out of the door like she’s going to be sick. We try to decide who should go after her, but then we notice Katy’s face has turned white. Her eyes are wet and terrified.

Katy? What’s going on? What do you know?

Just then, Sophie’s voice cuts through the din: What the fuck?

Katy bursts into tears. We rush to Sophie’s side. We forget about Molly. She’s gone, disappeared into the bowels of the ship. We follow Sophie back to our room, our arms around her as though we could physically protect her from what has already been done. We collapse onto the bottom bunks, crammed in together, a tangle of bare limbs.

Get that bag out of here now, Sophie commands.

We chuck Molly’s things into the corridor; we’ll deal with them later.

Sophie speaks first, telling us what she knows, then Katy fills in the gaps, in sodden, tremulous whispers.

Molly told Katy after we boarded the ship, the two of them alone in the toilets. She locked the door and said: Can I tell you something? Katy is a kind person. Of course she said yes. She didn’t know what was going to come next. How could she? Molly held on to Katy’s hand and asked what she should do. We didn’t ask Katy what advice she gave, why she didn’t snatch her hand away. It didn’t seem fair. She was put in a difficult position, an impossible position, by Molly. Who of us could say with confidence that we would have done the right thing, caught off guard like that? Still, when Katy tells Sophie that she knew, hours before the rest of us, she hangs her head in shame, shrinks up inside herself like a deflated balloon. Sophie listens to her, and we sit in silence for a long time, looking to Sophie to tell us what to do. She tells Katy it’s okay, but her voice is heavy with exhaustion, the weight of yet another betrayal.

So that’s why she didn’t come back to the room with us on the first night, we say, piecing it together. We didn’t realize she had been so drunk.

She wasn’t drunk, Sophie says stonily. She’s just a bitch.

One or two of us think back to the stories we heard over breakfast the day after that night. The ouzo, the falling over, the sick. But we, as a group, we say nothing.

Caroline and I search the labyrinthine corridors for Molly, to give back her bag and collect the room key. We find her sitting by an emergency exit, her head resting against her knees. She tries to talk to us.

Is Sophie okay? Can I speak to her? Please? I’m sorry, I’m so sorry.

She starts to cry, but we say no and keep our eyes lowered, simply pass over the bag and repeat the agreed-upon line: Stay away from her.

We find the teachers. We explain that Molly needs to be assigned to a new room. Later, we tell Sophie how the teachers went from room to room but none of the girls wanted her. There isn’t enough space in here, some said. We don’t want her in our room, others said plainly. We wouldn’t feel comfortable. The teachers were exasperated. Someone has to take her, they said. They asked the receptionist for another room, but there was nothing available. In the end, she was assigned to a disgruntled pair of first years who regarded her with disdain, as though she was riddled with disease, something they could catch.

She says she was drunk, but so what? She let herself get drunk. She always does – remember my birthday party? Molly chose to put herself in that position. She went to the boys’ room.”

We stayed up late that night, trying to make sense of it all. Sophie bought an overseas data package for her phone so she could update her relationship status and unfriend Molly and Leo on Facebook. Her sister phoned, then her mum. We expected her to cry, but there was only a quiet, white-hot fury, shining in her eyes.

What was it? she asked us, her captive audience. Did she have to prove to herself that she could get any guy she wanted? Was it some fucked-up power trip?

We murmured in agreement. It probably was.

She says she was drunk, but so what? She let herself get drunk. She always does – remember my birthday party? Molly chose to put herself in that position. She went to the boys’ room. No one made her. No one spiked her drink, did they?

We nod along and squeeze her hand, rub her back.

If she comes near me, Sophie says, I will end her.

We believe her.

—

The next morning, we eat breakfast on the ship. It isn’t as good as breakfast at the hotel in Athens. Fatty bacon and anaemic sausages, cereal like cardboard. We push the food around in puddles of grease, but Sophie fills herself up. She goes back for seconds, eating steadily, ravenously, until her plate is clean. Leo comes down to breakfast late, his hair wet, head hanging like a scolded puppy. He sits on the other side of the room with the boys. We avoid looking in their direction. The ship bobs up and down while we sip our flavourless coffees. We are exhausted, running on nothing but adrenaline and heady anticipation. Through the window, a bright line drawn between sky and sea. We share glances, wondering where Molly is, what will happen when she comes in, where she will sit. What will Sophie do? She would be entitled to tear her limb from limb and stick her head on a stake.

But she doesn’t come. We don’t see Molly for more than twenty-four hours. We disembark in the midday heat, spend the afternoon walking around Kuşadasi. We buy pashminas and postcards, look at jewellery, ceramics and other trinkets. Sophie doesn’t mention her all day, and we don’t want to bring her up, so we wait and wonder. We drink cocktails in the tangerine glow of the sun, our group of girls together, turned inward.

Molly appears the next evening. We see her leave the ship, flanked by teachers.

The only people who will still speak to her. And only because they’re paid to, Sophie says.

We nod along. Yes, yes, yes.

Maybe she’s fucking them as well.

We smirk.

Molly is wearing red shorts and a black T-shirt. She looks like a slut, we say, though the outfits we are wearing are not dissimilar. We pretend she doesn’t exist, yet at the same time we are very aware of her presence. It ripples through the group, like a bad smell we are pretending we haven’t noticed. We never look directly at her, but we know exactly what she is wearing, how much make-up she has on. When we laugh, we hope she notices what fun we’re having. When we whisper, we hope she thinks it’s about her. It isn’t, but that’s not the point.

We climb the steep hill to the old monastery, standing high on the hill of Hora. It is enormous, built like a fortress, the walls over fifteen metres high. Our guide shows us the small opening above the entrance, through which burning oil or lead was poured on unwanted visitors.

They say the screams were terrible, he says. You could see the skin melt from their skulls. It looks like nothing, just a little slit, but it saved the people of Patmos many times.

We move on. We look at paintings of all the miracles performed by St John. Our guide tells us we can visit the very place John had his visions of the final judgement – the cave of revelations.

If you make it there before the sun sets, he jokes. After dark it gets pretty creepy. He gestures back down the long slope, towards the sea, set ablaze by the sinking sun. It looks beautiful; it looks like hell. He keeps talking but we are all looking down at Molly, a shadow, an apparition, slinking back down the path on her own, towards the sea.

In the dark, our collective breath is a rhythmic shushing, like the slapping of the sea against the side of the ship, like a mountain breeze whipping through the trees.”

That night we dream of fires, of war, of violence and vengeance. The curse of the gods, severed penises, swallowed children, the relentless pull of fate. A fuck worth sacrificing a thousand men; a victory worth a young daughter’s life. We wake in our beds, hot, sticky and disoriented. Our eyes adjust to the darkness, and we remember where we are, drifting from one island to the next on an odyssey of our own. The room around us resolves into a simple cabin, each girl in her own bunk, her best friends asleep around her. In the dark, our collective breath is a rhythmic shushing, like the slapping of the sea against the side of the ship, like a mountain breeze whipping through the trees. We rock back and forth, back and forth, buffeted by Poseidon’s white-tipped horses, until we fall asleep once more.

—

The next day Molly tries to give Sophie a note. She corners her in the toilet and says, Please. Please will you just read it. But we crowd her out and tell her no. She’s already done enough.

Why doesn’t she say it to my face, huh? Sophie says later, when we are back in our room, her eyes hard and wide, her mouth drawn into an angry little pucker.

Sophie has been using her overseas data package to communicate with our friends at home, to make sure that by the time we get back to school absolutely everybody knows what happened. She says she is taking control of the situation. We nod. It is her right.

Apparently now she’s saying Leo took advantage of her, she says, rolling her eyes. I mean, please. She wasn’t that drunk. She was capable of saying no.

Yeah, we say.

She could have stopped it; she could have said no at any point.

Yeah, we say. Exactly.

It’s irrelevant that she thinks she was taken advantage of. It’s irrelevant that she was drunk. It doesn’t matter who instigated it. She went along with it. She needs to shut up and take some responsibility.

Yeah. We can feel a dark, painful aura radiating from Sophie. Yeah, we say. We can’t say anything else.

Of course I hate Leo too, she says. But at least he told me the truth.

We nod.

He shouldn’t have done it, she says. But I don’t know… it’s so much worse when a girl does it, isn’t it? When a friend betrays you like that, acts like your best friend when they know – she knew – she had betrayed me in the worst way possible. And I mean, you almost expect that kind of thing from guys.

Yeah, we say. We nod. Yeah.

—

Molly doesn’t eat with us for the rest of the trip. We never see her eating, only smoking alone on the deck of the ship, leaning against walls, trailing behind us through the frescoed rooms of the palace at Knossos, or lurking behind a pillar at the Acropolis of Lindos while the rest of us smile for a group photo. There are more countdowns: three, two, one… We smile! We are having so much fun! Her face is as blank as a statue.

We cannot speak to her, of course, but still we are curious, burning to know how it happened, how it really happened. We try to imagine Leo telling her shh shh, a sound like the sea, his face a pale moon above hers. We try to imagine her brain shouting no no no no no no and her body staying silent. We try to imagine her blurry, slurring ouzo-impaired perspective, her thoughts shunting and flashing, long moments lost to the hazy black hole of alcohol. We try to feel sympathetic, we do. But how hard is it to say no? How hard is it to push back, even through the fog? Had it been us, we would have pushed back, we would not have given in. But it wouldn’t have been us. That’s the difference between girls like us and girls like her. We never got as drunk as her. We didn’t do stupid things like dance in the street or fall over. We didn’t have the inclination to stay out late, especially with boys, even ones who were supposed to be our friends. What was she expecting? A sleepover?

And besides, it is so much easier to imagine her smiling coyly at him from across the room, full of intent, brushing up against him at the bar and whispering in his ear. It is easier to imagine her looking up at him through her thick lashes, biting her on her full bottom lip (because her lips are particularly full, aren’t they, her eyelashes particularly thick?) and him, rendered helpless by this act, and in the end, under the circumstances, who could blame him?

—

There was no confrontation, no big showdown like we were expecting, maybe even hoping for. Molly didn’t try to speak to Sophie again, and even if she had, we wouldn’t have let her. And Sophie, it seemed, truly did have nothing to say to her. It was old news by the time we got back to school. Someone else had done something shocking, something unforgivable, and within a few weeks Sophie was walking around school holding hands with a new boyfriend. Everyone’s attention turned to revising for our exams that summer. The trip to Greece became nothing but a washed-up memory.

For a few weeks, we acted as though Molly didn’t exist, but slowly we started speaking to her again, when we were in the same classes or drinking at the same pubs. It was as easy as walking through an open door or taking a sip of a drink already in your hand. After a while, it started to feel like maybe what happened wasn’t so scandalous. Sophie had moved on, so why shouldn’t we? And anyway, at the end of the day, people make mistakes, you know?

But though we wouldn’t say it to each other, sometimes, when we are drifting off to sleep at night, when our minds are still and empty, we dream of dark waves lapping against a shore, shh shh. A body in the bed next to us, possibilities unspooling like a ribbon of tape from a cassette. In each moment a choice made and a choice taken away. Infinite alternate universes exist briefly before disappearing, crystallizing into hard moments of action, inaction, here, now, something that cannot be dissolved, cannot be wound back, pushing us unstoppably towards an empty beach at night, a bed with sealed exits, a voice in the dark whispering. Don’t say anything, okay? Shh shh shh.

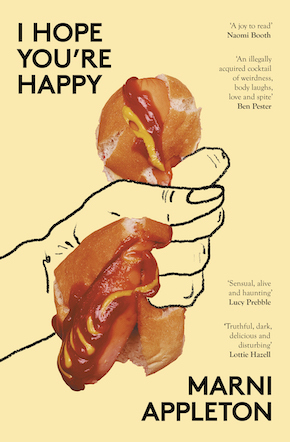

from the collection I Hope You’re Happy (The Indigo Press, £12.99)

—

Marni Appleton is a writer living in London. She holds a PhD in creative-critical writing from the University of East Anglia. Her writing has been published in literary and academic journals including Banshee, The Tangerine, Contemporary Women’s Writing and Comparative American Studies. I Hope You’re Happy, her debut collection of stories, is published in paperback by The Indigo Press.

Read more

@marniapp

@marniapple.bsky.social

@PressIndigoThe

Author photo by Ciaraìn Dowd